The orthodontic profession has lost its keenest scribe.

Eugene L. Gottlieb, DDS, founder of this journal, died peacefully at his home in Sedona, Arizona, on Oct. 11, after a short illness. He had turned 99 on Aug. 7.

Gene was born into an education-oriented family in the Bronx, New York, a generation or two removed from Russian Jewish immigrants. His mother Romola was a schoolteacher until she married his father Maurice, who taught business classes in high school and was renowned for never missing a day of work in more than 50 years.

It was a structured home life, but a time when the streets could be a bit rough for kids—we heard tales of burning potatoes in vacant lots and getting into fights. Gene also remembered meeting ballplayers from the Yankees and Giants in the local candy shop, way before ballplayers were millionaires. He was bright enough to have graduated from George Washington High School at 15, but because that was too young to enter Columbia College right away, he had to enroll initially in Teachers College.

Gene thought he would become a sportswriter, so while earning his bachelor’s degree in science, he worked as a sports stringer for the New York Herald Tribune and as sports editor of the respected school paper, the Columbia Daily Spectator. But a profession was a valued commodity in his family—his brother became a doctor, and his sister married a physics teacher who was later the long-time principal of the Bronx High School of Science. On the advice of The New York Times sports editor and of a respected uncle, Gene turned away from newspaper work and applied for Columbia Dental School in 1939.

Similar articles from the archive:

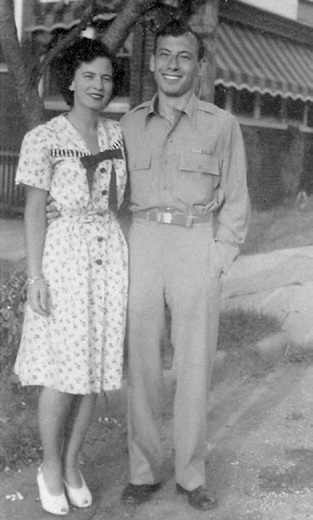

When World War II broke out, Gene finished his DDS degree under an expedited program and entered the Army as a dentist in 1943. He took time out from his training to marry his sweetheart, the former Jacqueline Levy, in New York. He was 23 and Jackie was 19. There’s a beloved family photograph from that time of Gene in his Army khakis, hand in his pocket, hatless with an already receding hairline, grinning as if he had the world by the tail, with the beautiful Jackie beaming beside him. They celebrated their 75th anniversary in May, still holding hands, at a hospital near their home where Jackie was recuperating.

Gene’s career as an Army captain basically consisted of traversing the Atlantic on troop ships. These young soldiers didn’t need much dental work, so he performed a number of other administrative duties. When the war ended in 1946, he left the service to start a family and a general dental practice in Rockville Centre, a town on Long Island. At first, his office was a curtained-off area of his one-bedroom apartment.

Always one to spot an opportunity, Gene saw that the kids in his practice needed orthodontic attention. That gave him the idea to apply to Columbia’s orthodontic program under the G.I. Bill. For the next two years, he commuted to school during the day and practiced dentistry at night. He earned his orthodontic certificate in 1949 and put out his shingle.

It was a time when orthodontic giants walked the earth, and Gene got to know all of them. He studied with Begg and Tweed. He eventually was on a first-name basis with the likes of Ricketts, Andrews, Roth, Graber, Proffit, Ackerman, Burstone, Reynolds—all the important figures in the specialty, and I’m sure I’ve omitted some who deserve mention. He described himself as an inveterate course taker, and he adapted everything he learned to his own practice.

In those days, at least, state law required the orthodontist to perform all intraoral tasks, so Gene operated for most of 25 years with only a receptionist. He must have been quite a craftsman, judging by the results he got from a hybrid Begg-edgewise system. Soon, he was attracting siblings and friends of his patients, and his practice was thriving.

Gene also applied every tidbit he picked up about practice building. In those days, of course, there was no advertising or social media; you spread your network by joining civic, religious, and dental organizations and getting to know more people. Jackie was active in the PTA and other groups. Gene became a leader in the local Tenth District Dental Society, serving as president and ADA delegate and putting his journalistic skills to use as editor of the society’s Bulletin.

During this time, in the early 1960s, he saw another opportunity. For the story of the founding of JCO, I recommend rereading an interview Gene did with our current Editor, Bob Keim, for our 40th Anniversary Issue in September 2007. He spent a great deal of time checking all the details of that interview, and it’s as thorough and accurate a recounting as you will find.

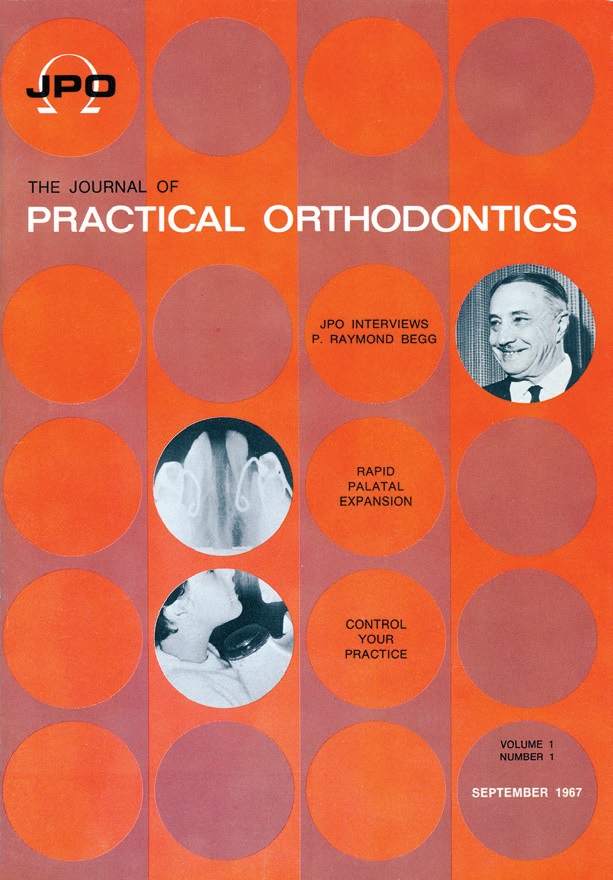

In summary, Gene and his professional colleagues were struck by the lack of an orthodontic publication devoted to the kinds of practical ideas he was picking up in courses and lectures and using every day in his office. So in 1965, he and two other New York orthodontists decided to start one. Gene, logically enough, would be the editor, Jerome Blafer the office manager, and Leo Taft the advertising manager. They obtained enough subscribers and advertisers to launch the Journal of Practical Orthodontics in 1967. By 1970, with the journal gaining traction, Gene had found (characteristically) that he could do all the jobs himself, had bought out his partners as they left to pursue other interests, and had changed the name to the Journal of Clinical Orthodontics, based partly on a suggestion from Jim Ackerman and Bill Proffit.

With both a busy practice and a growing journal on his hands, Gene found that something had to give. He and Jackie had been attracted to the Southwest since he took the Tweed course in Tucson, Arizona, and they both attended the 1960 AAO meeting in Denver. They came to love skiing in Colorado, so they began scouting communities up and down the Front Range. They settled on Boulder, he sold his practice, and they moved to Colorado in 1974. Gene had already bought a little 1902 house on Pearl Street that would serve as the JCO office until 2016. At that time, the block was on the outskirts of downtown Boulder; today, it’s an extension of the Pearl Street Mall, a lively stretch of shops and restaurants, and the office has been converted into a cluster of condominiums.

Jackie and Gene’s house in the foothills west of town had spectacular views, but the elevated locale turned out to be a snow catcher in the winter. They started looking farther southwest and found a property among the stunning Red Rocks of Sedona. They built their dream retirement home and moved there in 1987.

Gene and Jackie Gottlieb after their marriage in 1943.

First cover of Journal of Practical Orthodontics, September 1967.

Gene never really retired from JCO. He stepped aside to some extent in 1988, becoming Senior Editor when Larry White was appointed as Editor. Bob Keim took over the Editor’s chair in 2002. All the while, Gene kept writing and maintained a firm hand on the editorial rudder. Even in his last years, when his eyesight had deteriorated, he reviewed every submitted article to make sure it was in keeping with the journal’s mission.

That mission was stated in the very first JPO Editor’s Corner, published in September 1967 and so succinct that I can quote it in its entirety:

JPO is a journal of orthodontic practice.

It was conceived as a meeting place for orthodontists to share their knowledge and experience. While it will not neglect areas of basic information and philosophy of treatment. JPO will concentrate on the treatment of the orthodontic patient and the administration of the orthodontic office.

Given a continuing interest in the basic science of orthodontics, it is the sharpening and honing of techniques of treatment and administration that offer immediate rewards to the orthodontist and his patient in terms of treatment results accomplished in a better, easier and quicker manner. Quality need not be sacrificed in the name of speed. Gadgetry need not be encouraged as a substitute for system.

Communication and the maximum interchange of ideas mark the age in which we live. The more knowledge we have about how to do things, the less likely we are to try to solve all problems in the same manner, with the same treatment.

We can all learn from each other. Let JPO be a window on the orthodontic world today. Bring to this Journal what you can share with your colleagues. Take from this Journal what you need, to treat the case better, to run the practice more smoothly, to advance this wonderful specialty in which we serve.

The JCO editorial formula was built into Gene’s DNA, but it wasn’t hard for anyone to decipher. His model was not the academic journal, but The New York Times. Our Guide for Contributors still spells it out: “Use a clear and concise reporting style. JCO reserves the right to edit manuscripts to accommodate space and style requirements.” Gene wielded a sharp pencil, and that was the key to the journal’s success. After the initial review process, any submission was (and still is) subject to rewriting to make it readable and usable for the practicing orthodontist. “The story starts on page 5,” Gene would say of a paper that began with the complete history of orthodontics.

In the beginning, Gene and a few contributors produced most of the material from their own practices. In editorial conferences years later, Gene would often look at a new submission involving some little technique and say, “I published that idea years ago.” We would look it up, and sure enough, he had written up a similar procedure in 1969 or 1972. Eventually we wised up and quit checking him.

But as a private publisher who needed material, Gene also had to be a talent scout. He found that his friend Sid Brandt liked to do interviews, so they established the JCO Interview as an art form, inviting all the movers and shakers of the profession to explain their philosophies in their own words. Gene would hear speakers like Tom Mulligan, Larry Andrews, and Wick Alexander and persuade them to publish by helping them turn their lectures into series of articles. Many of the series became standards of the orthodontic literature, as demonstrated in our September 2017 50th Anniversary Issue. Gene found rising international stars such as Jim McNamara, Bjorn Zachrisson, and Birte Melsen and brought them into the JCO stable of editors and writers. Some of these speakers were featured in the live JCO Seminars that were popular in the 1980s and early ’90s (basically until the target audience of American orthodontists had heard all the lectures).

Gene’s monthly Editor’s Corners became an institution in the specialty. When he watched sporting events, he tended to turn off the sound because he was annoyed by the commentary and wanted to do his own mental analysis. That was the way he observed orthodontics, like a sportswriter scanning the field from the press box. He would take a subject that had caught his attention, perhaps from the newspaper or a magazine or the nightly news, later from the Internet, and mull it over until it had turned into a pertinent topic for the everyday orthodontist. These Editor’s Corners are all still freely available in our online archive, and I think if you browse through them, you’ll come away amazed at Gene’s perspicacity.

One of his frequent topics was the business of orthodontic practice. Remember, his father had taught business in high school, but nobody was teaching orthodontic residents how to set up and manage their offices in those days; they had to learn on the fly. Gene began a nine-part series called “Control Your Practice” in the first issue of JPO, and from then on, the journal became known for its management advice. Subjects such as motivating your patients, raising your fees on a regular basis, computerizing your billing, and selling your practice were first raised to the specialty as a whole by JCO. Popular departments like Orthodontic Office Design (with Warren Hamula) and Management & Marketing (with Mel Mayerson, Skip Iba, and now Bob Haeger) carried on the tradition. Gene eventually lectured at AAO annual sessions and around the world, usually speaking about management.

It wasn’t enough for him just to point out best practices derived from the Harvard Business Review, Forbes, and other leading financial resources; Gene wanted to know what U.S. orthodontists were actually doing in terms of administration and management, so he would have a frame of reference for suggesting improvements. Thus began the JCO Orthodontic Practice Study. Every two years starting in 1981, practitioners from around the country have provided details about their income, numbers of patients, staff policies, and management methods. The responses are compiled anonymously and tabulated for publication in JCO, along with a commentary on salient trends. Data from the first study were recorded on digital tapes and run through massive mainframes at the University of Colorado. Now, the survey is conducted online and analyzed on a laptop. The biennial Orthodontic Practice Study and its companion JCO Study of Orthodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Procedures (which started in 1986 and is now run every six years) are still the most authoritative sources of information on how American orthodontists practice.

Even as he got older, Gene never shied away from innovative concepts. He printed an article about office computing in 1974. In 1983, he was the first to publish a paper about the possibility of skeletal anchorage—in this case, from a screw inserted in a patient’s nasal cavity by Tom Creekmore and his pediatric dentist. Gene was quick to recognize the ramifications of corporate dentistry, tooth positioners (the forerunners of clear aligners), lingual and cosmetic brackets, accelerated treatment, and three-dimensional imaging. Go back and read a classic Editor’s Corner, “One Giant Step from Flatland to Spaceland,” from September 1984.

By my count, Gene attended some 60 consecutive AAO annual sessions. He would roam the halls and table clinics to pick up ideas and potential writers, often being waylaid by friends and authors; when we started running a JCO booth in 1997, he held court there. A number of subscribers, familiar and unfamiliar, would (and still do) come by just to tell us, “This is the journal I always read cover to cover.” That was music to his ears. He kept going to the conventions every year until he was too frail to travel. His last out-of-state trip was in 2010, when he came to Colorado to see his newborn great-granddaughter, Isabelle.

Gene was a patriarch of biblical proportions not only to his son John and daughter Cindy—whom I had the great fortune of marrying after we met in graduate school—but even to my side of the family, especially after my own father died 30 years ago. He nabbed me right after my Army service, when I had planned to continue my career as a sportswriter (sound familiar?). My first test was to transcribe and edit the McNamara interview on the Fränkel appliance that we published in May-June 1982. I must have passed, because I’ve been with JCO ever since.

Gene’s travels with my son Philip were legendary. He remembered being afraid of his own grandfather, so he didn’t want his only grandson to have the same experience. They went to England during school vacation just before Philip turned 8, and for about a decade they took a trip somewhere in the world every summer. They would carefully document their destinations with photos and videos, and each time Gene would write a synopsis entitled “Philip and Gene Go to Africa”—or Japan, Morocco, Egypt, even Papua New Guinea. Such was his gravitational pull that Philip is now also working for the journal (after passing up a career in sports broadcasting), as the third generation of ownership. You might say that as a family, we’re better suited to dental journalism than to sports journalism.

Gene’s impish sense of humor only occasionally peeked through the pages of JCO, but he was widely known to friends and family as a wit and raconteur. At one long-ago AAO meeting, it was Gene’s birthday every night he and his buddies went out to dinner, just so they could get the free dessert and the celebration. Many of his turns of phrase became family aphorisms. He loved to tell a good joke, sometimes off-color; those were the only times I ever heard him use foul language.

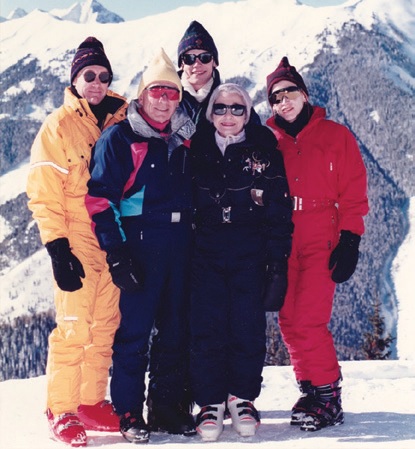

In fact, he was the picture of moderation until the day he died. During his last few years, he would drink one tiny glass of vodka on the rocks to keep everyone company. I don’t know if he ever had his body fat measured, but it probably wouldn’t have registered on the scale in any case. Gene and Jackie continued skiing, mostly in Colorado, into their 80s—old enough to get free lift tickets. They took up tennis back in New York and continued to play well into their Sedona days.

A child of the Depression, Gene was a smart but careful investor. He never borrowed money from anyone other than his own company. He would always remark how great a country we lived in, where you could take an idea and turn it into a successful enterprise. Not that he didn’t ever worry about politics, but then he was a world-class worrier—no doubt because he was such a deep thinker. He could worry an issue like a dog on a bone; we might think we had buried it, but he would dig it up again a year later. The one thing he didn’t worry about, however, was his wardrobe. Jackie has always been an elegant dresser, and while Gene could dress up nicely when the occasion called for it, she was constantly hectoring him to buy a new shirt or a new pair of pants. “I already have a pair of pants,” he would answer.

All in all, Gene was a sunny optimist who lived a long, full life with few regrets. The only one that comes to my mind is that he was never able to invent a gadget that would be commonly used all over the world. As an incorrigible tinkerer, he certainly tried. A bagel slicer got as far as the prototype stage; he tried to improve on the clothes hanger; and he conceived of a battery-powered handwarmer for ski poles (still a fabulous idea if anybody wants it). His one great invention turned out to be JCO, which is indeed commonly used all over the world—the last issue shipped to 82 countries.

Family ski trip in Aspen, Colorado. Left to right: David Vogels, Gene Gottlieb, Phil Vogels, Jackie Gottlieb, Cindy Vogels.

Gene also had a connoisseur’s eye for art and antiques, probably inherited from his father. He was always on the lookout for the hidden bargain that no one else would spot. If you’ve ever visited his and Jackie’s home in Sedona, you’ll recall that it’s laid out almost like a museum, full of outstanding collections of art glass, Southwestern and Modernist art, rugs, and antiques. Gene and Jackie traveled as far as Russia, Japan, and Bhutan, and they always brought back fine examples of folk art, from wooden toys to Japanese plastic food. Some of the masks they collected turned into colorful covers for JCO. Gene was a partner in New York’s E.J. Morrison Antiques from 1957 to 1974, and he helped launch the Sedona Arts Festival and Sedona Cultural Park, serving as their treasurer from 1991 to 1997.

Gene never wanted any fuss or ceremony about his accomplishments. I didn’t ask his permission to write such a long encomium—but as he always said, never ask a question if you don’t want to hear the answer. Although I can’t think of anyone more deserving of an award for service to the orthodontic profession, he wouldn’t countenance any campaigning for such honors. He sensed some resentment from the establishment in the early days of JCO because he was seen to be competing with the American Journal of Orthodontics, but he had no desire for competition with any other journal; JCO was intended simply as an alternative. Relations with the AAO certainly warmed over time, and Gene was gratified when he was asked to contribute to the centennial commemoration of the AJO-DO and when Rolf Behrents and other editors readily agreed to write essays for our own 50th Anniversary. We surprised him two years ago by announcing the Eugene L. Gottlieb JCO Student of the Year award, sponsored by American Orthodontics, but it was only a fitting recognition of his lifelong commitment to clinical orthodontic education. The brainchild of my son Phil, this program has already helped three residents to start their practice careers, and the fourth competition is now under way.

You might be wondering what changes are in store for JCO. Although Gene had not been involved in day-to-day operations for some time, we will obviously miss his eagle eye as a reviewer. To fill that gap, we plan to add one more editor or other outside peer reviewer for each article to supplement our already stringent acceptance process. We had already redesigned our print and online looks as part of our 50th Anniversary observance last year, and Gene heartily endorsed that modernization. In summary, therefore, I don’t believe you will see much difference in the presentation of clinical material you receive every month.

One change you might notice is that, with the gracious consent of Editor-in-Chief Bob Keim, we have raised Gene’s name to the top of our masthead, where it will remain as long as this is a family-owned publication. But I know Gene would agree that the greatest tribute you could pay him as Founding Editor of JCO is just this: Keep reading.

DAVID VOGELS

Executive Editor

Editor’s Note: The January 2019 issue of JCO, beginning what would have been his 100th year, will be dedicated to Gene Gottlieb. In addition to our regular articles, we will publish any anecdotes, reminiscences, or tributes you would like to submit. In keeping with Gene’s spirit, please make your contribution as succinct as possible, and we in turn will edit as lightly as possible. Send your text to editor@jco-online.com no later than Dec. 20, 2018, and be sure to include your full name, degrees, and title as you would like them published in the issue.