Correction of Palatally Displaced Maxillary Lateral Incisors Using a Tube System

The Power of the Pyramid

This fall, I had the honor of serving as one of the speakers at the Pacific Coast Society of Orthodontists' annual session, held in Monterey, California. Under the theme of "Emerging Tools and Technologies", various lecturers covered topics pertinent to a progressive 21st-century orthodontic practice: temporary anchorage devices, cone-beam radiology, and digital models for the doctors; paper-free office technology, minimalist marketing approaches, and team-building techniques for the staff.

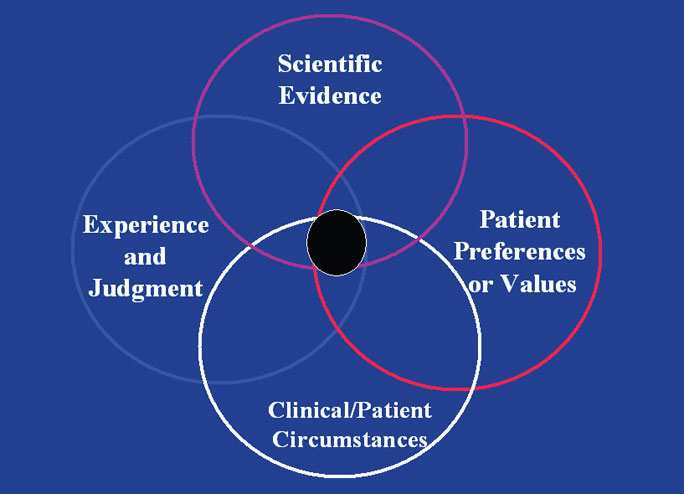

Given the pragmatic nature of JCO, I was asked to speak on "Varying Concepts of Evidence-Based Treatment Modalities". My main argument was that there is not a division or debate between "evidence-based" and "experience-based" practice, but rather a mutually beneficial continuum between the two philosophies. According to a new book by Jane Forrest and Syrene Miller, evidence-based practice should be defined as "the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values".1 In this important paradigm, the clinical judgment of a skilled practitioner and the patient's individual preferences and values are given equal weight with scientific evidence in the decision-making process (Fig. 1).

Similar articles from the archive:

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER The Weight of the Evidence March 2004

- JCO INTERVIEWS Robert G. Keim, DDS, on Living with Statistics May 1997

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER Down with Dogma November 2004

Clinical experience alone is not enough, because clinicians tend to practice the way they were taught in school despite whatever progress may occur, and there will always be local and regional variations in treatment techniques. In contrast, the accumulated scientific evidence becomes a universal guide that any professional may consult to stay up to date. Furthermore, the public has greater access to clinical information than ever before, thanks to the Internet and an increasingly sophisticated popular press. Most of our patients' parents and adult patients today know how to evaluate relevant research for themselves.

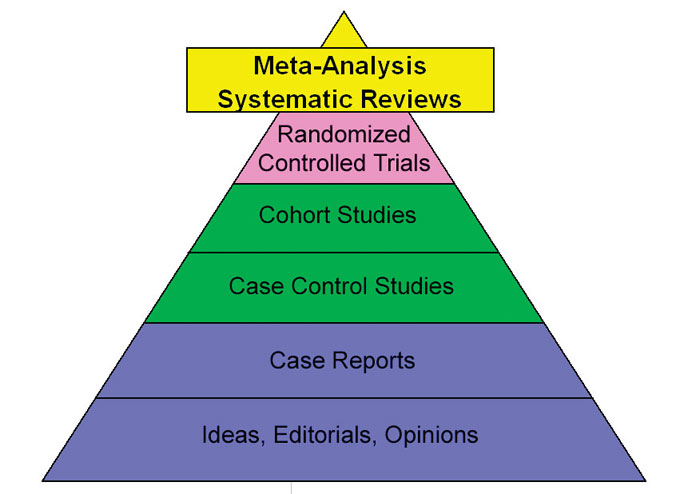

In the model of Forrest and Miller, there are seven levels of evidence (Fig. 2).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are found at the top of the evidentiary pyramid, just ahead of randomized controlled trials, and thus should constitute the "best evidence" for our clinical decisions. When we attempt to put this philosophy into practice, however, a real problem arises. Preparing for my PCSO presentation, I did an electronic literature search on PubMed and found citations for 33,249 orthodontic papers as of early October 2007. These papers could be considered the current "evidence" of orthodontics, but I wanted to know what proportion of them fell into the "best evidence" category. When I refined my search, I ended up with only 31 orthodontic meta-analyses in the PubMed data base. Papadopoulos and Gkiaouris pointed out the same shortcoming in a paper published earlier this year2; in fact, they found that only 16 of these 31 studies fit the criteria of true meta-analyses. If that is the case, then only about .048% of the papers in the orthodontic literature can be relied upon as our "best evidence".

So how are we to make our clinical decisions? Well, in my simple view of the world, if no "best evidence" is available, we use the "best available evidence".

Returning to the hierarchy of Forrest and Miller, we see that the base of the pyramid consists of two layers: one for case reports and one for ideas, editorials, and opinions. Without a strong base or foundation, the entire pyramid would crumble. Everything else would be meaningless. As it happens, publishing clinical case reports and practicing orthodontists' ideas, editorials, and opinions--or, as Gene Gottlieb described it so well in our Editor's Corner last month, "experience-based orthodontics"--is what JCO is all about.

There is no doubt whatsoever that "more well-conducted, high-quality studies are needed to produce strong evidence in orthodontics".2 If researchers and academic departments keep at it, the "best evidence" in orthodontics, the studies at the peak of the pyramid, will proliferate exponentially in the future. In the meantime, those of us at the base of the pyramid will continue to serve as a strong foundation, supporting the levels above us, as we present the "best available evidence".

RGK

REFERENCES

- 1. Forrest, J.L. and Miller, S.A.: Evidence-Based Decision Making: A Translational Guide for Dental Professionals, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2008.

- 2. Papadopoulos, M.A. and Gkiaouris, I.: A critical evaluation of meta-analyses in orthodontics, Am. J. Orthod. 131:589-599, 2007.