THIS ARTICLE WILL BE MOVED TO THE ARCHIVE IN OUR REGULAR FORMAT WITH PART 2 WHEN THE JUNE ISSUE IS PUT ONLINE

The material contained in this communication is subject to change based upon federal, state, and local regulations; guidance from agencies; and additional knowledge that will come to light throughout the COVID-19 crisis. This information was organized to provide assistance and not specific direction; further due diligence is still required. Decisions for any specific orthodontic practice should be based on your own considerations and requirements, after consulting with professional advisers who are involved in all aspects of your practice.

Orthodontics in the COVID-19 Era: The Way Forward Part 1 Office Environmental and Infection Control

SRIRENGALAKSHMI M., BDS, MDS, MOrth*

ADITH VENUGOPAL, BDS, MS, PhD

PAOLO JESUS P. PANGILINAN, DMD

PAOLO MANZANO, DMD, MScD

JASSIN ARNOLD, MSc

BJÖRN LUDWIG, DMD, MSD

JASON B. COPE, DDS, PhD

S. JAY BOWMAN, DMD, MSD

The current pandemic, known as COVID-19, could not have been more predictable. It marks the return of a familiar enemy. Throughout human history, nothing has killed more people than the viruses and bacteria that cause disease.

As COVID-19 is painfully demonstrating, our interconnected global economy helps spread new infectious diseases and, with its long supply chains, is uniquely vulnerable to the disruption that the virus has caused. The ability to get to nearly any spot in the world within 20 hours, especially since we may be packing a virus along with our carry-on luggage, permits new diseases to emerge and grow when they might have died out within smaller regions in the past. For all the advances we’ve made against infectious disease, it seems civilization’s progress has also made us more vulnerable to microbes that evolve 40 million times faster than humans.1

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a highly infectious disease caused by the newly discovered coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. On Jan. 8, this novel coronavirus was officially regarded as the causative pathogen of COVID-19 by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.2 The epidemic of COVID-19 started in the region of Wuhan, China, last December and has since become a major public-health challenge, not only for China, but for virtually all countries around the world.3 On Jan. 30, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that this outbreak constituted a global public health emergency4 and declared it a pandemic.

Results from the study of Lauer and colleagues estimated the median incubation period of COVID-19 to be 5.1 days; 97% of their respondents who were infected and developed symptoms did so within 11.5 days.5 Backer and colleagues assessed the mean incubation period to be 6.4 days, ranging from 2.1 to 11.1 days.6 According to the WHO COVID-19 Situation Report-73, this incubation period is also known as the “pre-symptomatic period” in which infected patients become contagious, suggesting that transmission can occur before symptom onset.7

A study by Santarpia and colleagues on the transmission potential of COVID-19 in viral shedding observed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center indicated that COVID-19 is spread to the environment as expired particles, found during toileting and through contact with fomites as well as spread through direct contact.8 Such contacts include person-to-person and droplet transmission, along with indirect contact from contaminated objects and airborne transmission, thereby supporting a focus on airborne isolation precautions.

Keep in mind that the key to Infection = Exposure to Virus × Time. For instance, following a recent two-and-a-half-hour choir practice attended by 61 members (unfortunately including one undiagnosed symptomatic index patient), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 87% developed COVID-19.9 How many hours in a clinic day might you find yourself in an environment where you could, in close proximity, encounter multiple possible “vectors”? This has led the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to release recommendations for dentistry beyond “standard precautions,” now including both “contact” and “droplet” precautions.

Consequently, all dental professionals, including orthodontists, are at a high risk of acquiring COVID-19 through multiple transmission routes, including7:

- Respiratory droplets from coughing and sneezing that may occur during a dental or orthodontic procedure. A single cough can release 3,000 droplets at 50mph and a sneeze, 30,000 at 200mph, with perhaps 200 million virus particles expelled. This increases the possibility of inhaling at least 1,000 virus particles, apparently required to establish an infection.

- Indirect contact, in which viral droplets fall onto a surface that the dental professional or orthodontist later contacts.

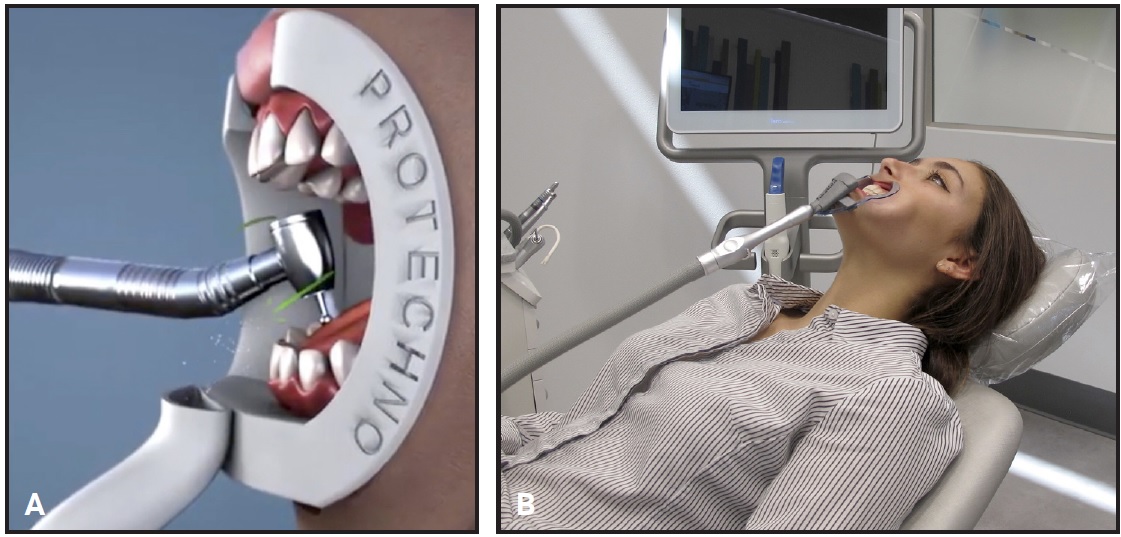

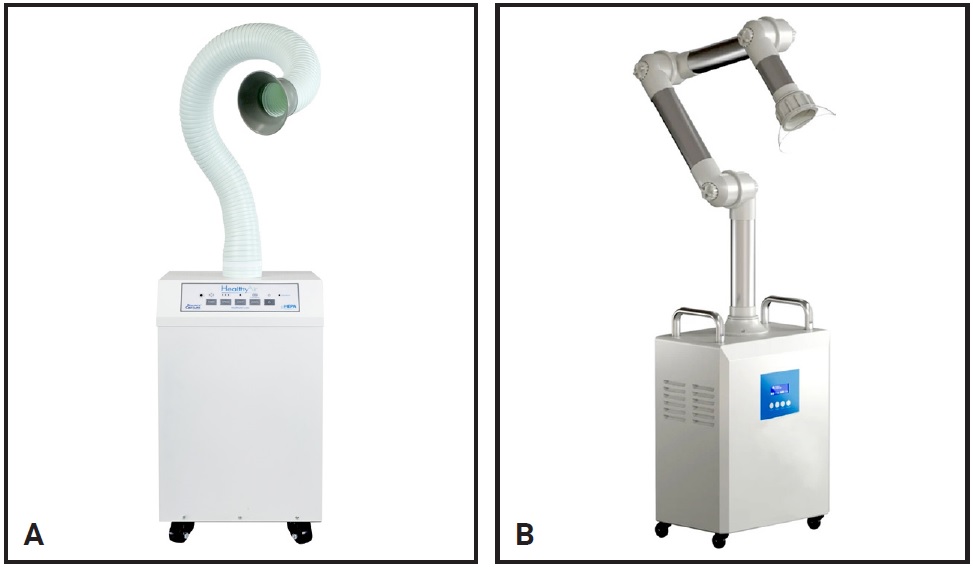

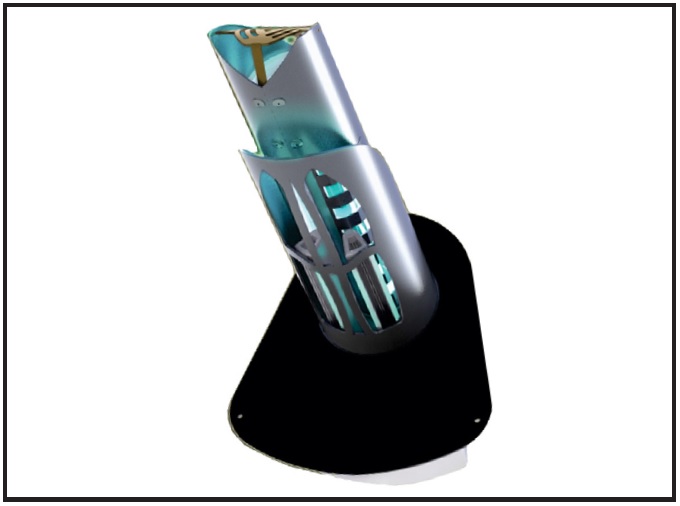

- Aerosols created during dental or orthodontic procedures.

- Treatment of patients who may have experienced indirect contact transmission themselves from removing and replacing aligners, appliances, or elastics.

- Contact or exposure time with multiple such persons, including those who accompany the patients. Asymptomatic vectors or carriers who might unintentionally spread the virus by breathing, speaking (with perhaps 20 virus copies released per minute10), or singing,9 even in the absence of physical contact.

As SARS-CoV-2 has also been identified in the saliva of infected individuals, it poses a significant risk for dental professionals and their patients.2

As of this writing, there are 210 countries or territories affected by the virus. Many of these countries have established quarantines or lockdowns according to the alarming epidemiological risks involving the highly infectious state of the virus and the general susceptibility of the population.

Thanh Le and colleagues pointed out that vaccines have been in development since the release of the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 on Jan. 11.11 This has led to the start of at least one clinical trial of unprecedented speed since March 16. Given the imperative for speed, there is an indication that vaccines should be available by early 2021 or, with luck, even earlier. This would represent a fundamental change from the traditional vaccine development, which takes an average 10 years, with five years representing one of the fastest.

Most orthodontic treatments are not life-threatening or part of a high-priority triage; a procedure could be considered an “emergency,” however, when an orthodontic appliance loses its integrity. Situations like swelling, soft-tissue damage, difficulty in opening the jaws, longstanding ulcers,

and inadvertent tooth movements may merit a high-priority need for dental attention. Even when scientists have found suitable treatments and vaccines, however, the handling of orthodontic patients may continue to be a challenge.

Due to economic constraints, governments are expected to gradually lift the lockdown restrictions and, in turn, permit the resumption of routine dental and orthodontic operations. This is when the serious potential for a “second wave” of COVID-19 is likely to occur.12

Feeling Conflicted?

In lieu of the upcoming relaxation of the lockdown restrictions in various countries, a thorough knowledge and understanding of sterilization and disinfection protocols is required, along with good scientific and clinical reasoning.13,14 The dichotomy of attitudes and responses to this pandemic has been extreme, ranging from, “We already use standard precautions in our practice, so you won’t even see any ‘sneeze guards’ at our reception desk,” all the way to quitting dentistry or dental hygiene due to the risks. Public perception will also be at work, especially considering that on the way to your practice, patients may encounter various protective measures such as those found at fast-food restaurants and chain stores. Decisions about changes in how we practice will likely be dictated by regulatory agencies (and it is most important to review their proclamations regularly) but, presumably, also supported by individual professional judgment. It’s a bit like investing—how risk-averse are you?

Although unlikely, the advent of contact tracing could result in quite a marketing challenge for any practice “traced and targeted” as even an asymptomatic “Typhoid Mary” source of an outbreak in its area. Consider, too, the recent incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children15-18 (while children do have a lower mortality rate, even one loss is too many), along with the reported potential for 25% of asymptomatic carriers to slip through the cracks into our practices. In fact, recent OSHA guidance (not mandates) could create legal liability risks for reopened practices if the virus is transmitted in the dental environment.19 A recent communication from the ADA stated, “This guidance is intended to help dental practices lower (but not eliminate) the risk of coronavirus transmission . . . not presume that following the guidelines will insulate them from liability in case of infection.”20 Seeking professional advice on how to handle a patient or staff member who develops COVID-19 sometime after a visit to your practice is certainly warranted. All this signals that there is an inevitable “new normal” ahead of us, although some may negotiate changes with heels dug deep along the way.

It was 35 years ago that one of the authors remembers first donning gloves and stating that, “There is no way I’ll ever be able to bend wires with these on.” A bit later, the practice of dipping orthodontic pliers in a solution for disinfection (at least until the next patient presented) evolved into autoclaves and, now, even the hiring of infection-control specialists for advice and training.

This article was not composed as an exercise in alarmism or “virtue signaling,” but rather is intended to provide orthodontic practitioners some guidance—or at least food for thought—on precautions to be taken for the treatment of orthodontic patients in a post-lockdown era, until at-home or in-office testing, vaccines, or successful treatments for COVID-19 are developed. Please consider the following touchstone when evaluating any decision made during this crisis: “What’s the downside of a bad decision?”

Sterilization Protocols

Dental professionals should be familiar with how SARS-CoV-2 is potentially spread, how to identify patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and what extra-protective measures should be adopted during practice to prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Here, we reinforce the standard infection-control measures that should be followed by dental professionals, though these may be subject to alteration and addenda, considering that aerosols and the droplets they arise from are presently considered the main spreading routes of SARS-CoV-2. In contrast, it appears that experts cannot agree about the significance of aerosol transmission, at least in terms of virus-laden “micro” aerosols smaller than 5μm in diameter. We might apply the aphorism, “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” or argumentum ad ignorantiam: a common fallacy of logic. Advance knowledge certainly allows for advance preparation: forewarned is forearmed.21

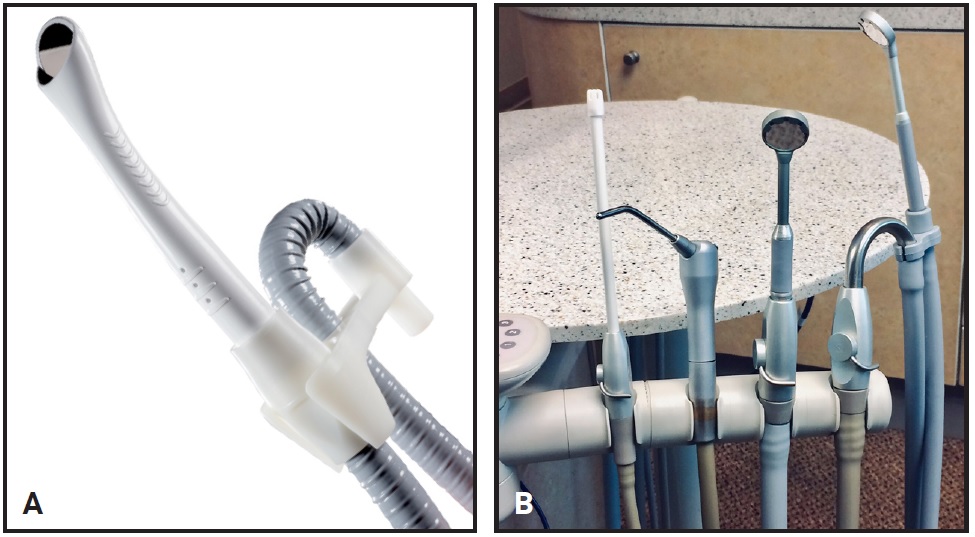

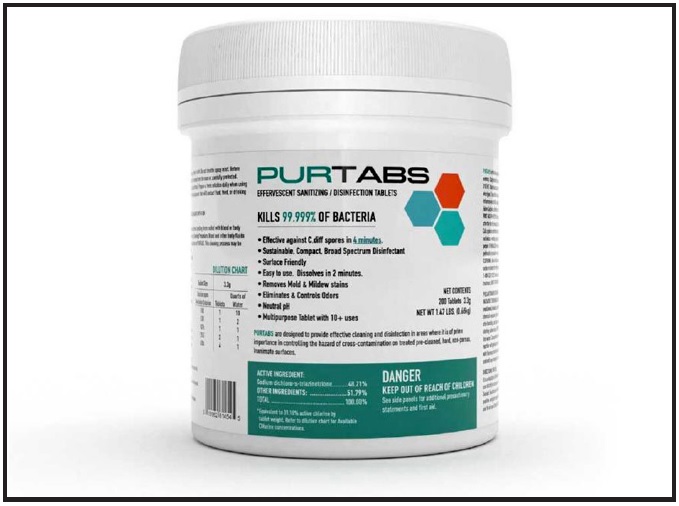

Many of our suggestions are based on Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19 established by the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970.22 The ADA recommends that all surfaces of the clinic, especially those frequently touched, be wiped with Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered surface disinfectants and that instruments be autoclaved along with dental handpieces. It is important to review the manufacturer’s instructions for use of any product mentioned in this article.

Medical waste, including disposable personal protective equipment (PPE) after use, should be transported to the temporary storage area of the dental facility in a timely manner. Reusable instruments and other clinical items should be cleaned, sterilized, and properly stored in accordance with the CDC Guidelines for COVID-19 Medical Waste Disposal.23,24 The CDC notes that “medical waste (trash) coming from healthcare facilities treating COVID-19 patients is no different than waste coming from facilities without COVID-19 patients.” CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food-service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures. There is no current evidence to suggest that facility waste needs any additional disinfection.

Pre-Appointment Screening and Triage

Triage includes establishing an office hotline for tele-consultation that can be used to determine the need for a patient to visit a health-care facility or provide support in following social-distancing protocols. Our teams should also inform patients on preventive measures to undertake before they come to our offices. Screening or self-assessment tools as published by CDC and the Mayo Clinic include the following questions25,26:

1. Have you recently participated in large gatherings and/or gatherings of people unrelated to you?

2. Have you traveled to or reside in a country/area reporting local transmission of COVID-19?

3. Have you been within six feet of a person with a lab-confirmed case of COVID-19 for at least five minutes, or had direct contact with their mucous or saliva, in the past 14 days?

4. Have you had any of the following symptoms within the last 48 hours?

- Fever of 100.4°F or above, or potential fever symptoms such as alternating shivering and sweating

- Cough

- Trouble breathing, shortness of breath, or severe wheezing

- Chills

- Muscle aches

- Sore throat

- Diarrhea

- Loss of smell or taste or change in taste

5. Were you a patient who has recovered from COVID-19?

If all answers are NO: Appointment can be scheduled to manage orthodontic emergency.

If any or all of questions 1, 2, or 3 were answered YES: Recommend self-quarantine procedure first, secure clearance, and screen again.

If any or all of questions 1, 2, 3, or 4 were answered YES: Refer the patient to a hospital for management.

If question 5 was answered YES: Patient should secure clearance first

Separation of Powers: New In-Office Roles

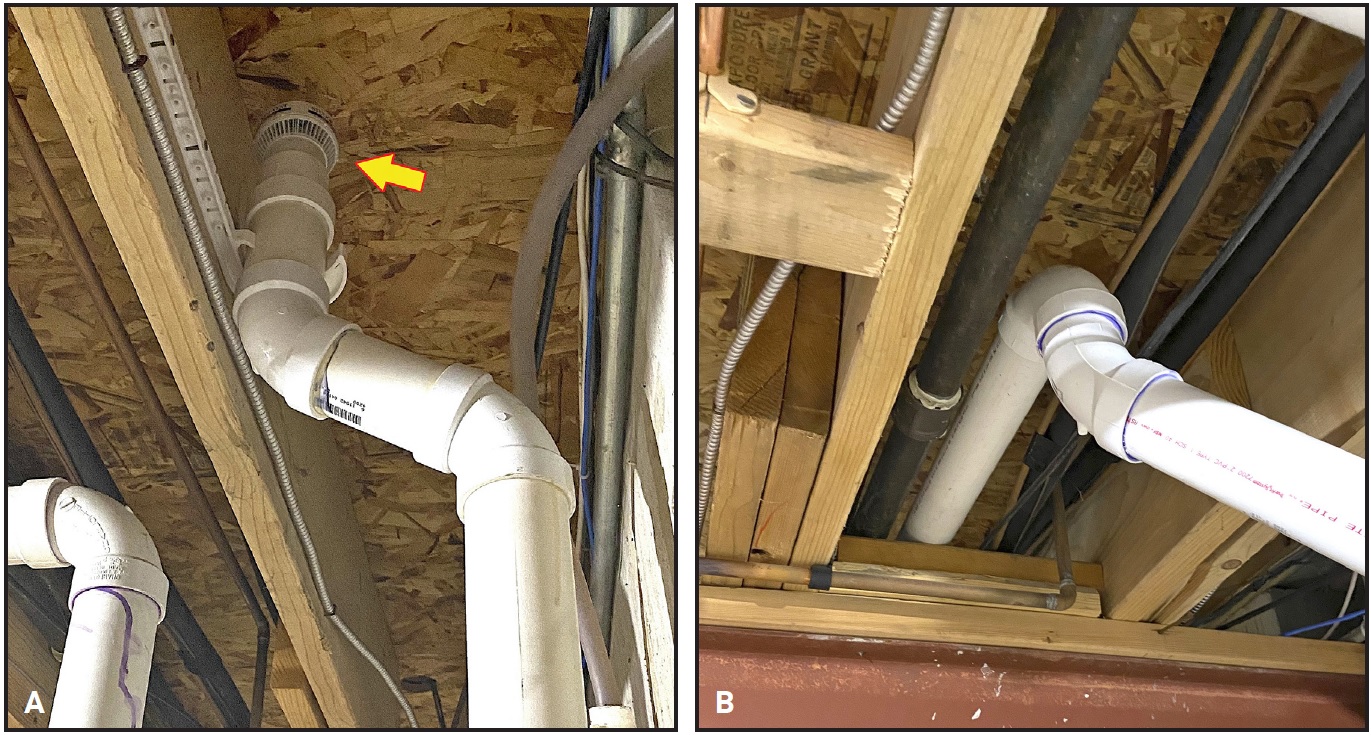

In this new environment, there may be new roles and job descriptions for staff with considerations for social distancing. The clinical staff should be segregated from reception and administrative staff using a virtual or physical “redline” on the floor or even an actual door, with the intent that, as Kipling wrote: “Never the twain shall meet.”

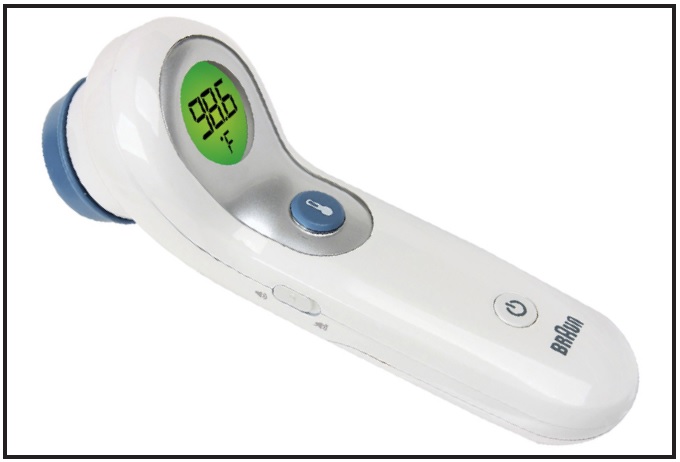

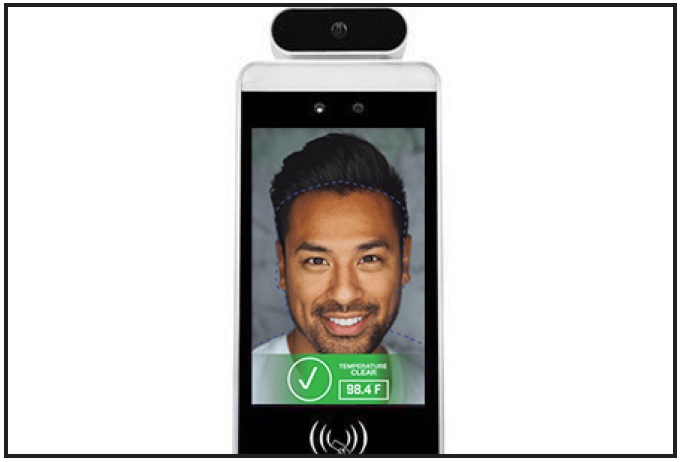

As patients present to our offices, they can inform us of their presence by phone, text, or a video option such as doxy.me or Zoom. The role of a greeter (or patient screener) includes asking screening questions, providing information about what to expect during the appointment, and noting specific concerns or questions the patient would like answered. The greeter (wearing appropriate PPE) instructs the patient to come to the practice entrance alone, wearing his or her own mask or scarf, and records a screening temperature. Other persons accompanying a patient will remain in their “waiting room”: their own vehicle in the parking lot.

After patients are directed to wash their hands or use provided hand sanitizer, the greeter directs them to the clinic area. They will be met by the scribe (or communications assistant) wearing appropriate clinical PPE. The role of the scribe is to welcome and dismiss patients from the clinic area without any actual treatment contact. The scribe also charts any information for the appointment, generates orders or prescriptions, takes clinical photographs, and obtains needed supplies. Although wireless and “washable” keyboards and mice are available from companies such as Seal Shield, only the scribe will use the computer, thus avoiding cross-contamination and PPE waste.

Arranging orthodontic chairs in an open bay to create a minimum of social distancing may necessitate halving capacity by working in pairs of chairs, or possibly separating units with room dividers. A second orthodontic assistant works in tandem with the scribe for each set of chairs. While one chair is occupied by a patient, the other is disinfected and left vacant. Upon completion of the appointment, the scribe directs the patient back to the reception area for egress out to the vehicle. The scribe then communicates with the parent by phone, text, e-mail, or better yet, video chat, reporting on progress, procedures accomplished, concerns, and recommendations. If video connection software is being used, the orthodontist can also be brought in on the conversation without physically meeting the parent. This saves the doctor’s time and avoids the waste of doffing and donning PPE for a trip to chat with each parent.

Feeling the Heat

It appears that the taking and recording of temperatures for staff members, patients, and even service personnel may be de rigueur going forward. Employee and patient screening forms (hard-copy, digital, or a combined temp-time clock) can be used to log the required daily health questions and temperatures.