A New Nickel Titanium Rapid Maxillary Expansion Screw

Perceived facial attractiveness is strongly dependent on an esthetic and harmonic smile, since attention during social interactions is directed primarily to an individual’s smile and eyes.1 Although smile esthetics have been highlighted in the media through the promotion of beautiful faces and harmonic smiles, the teeth in most of the population are not in perfect balance with their surrounding structures.2 Still, people with smiles that are considered esthetic are perceived as having higher social and intellectual standing than those with unesthetic smiles.1,3

The relationship between the visible dimensions of teeth in an esthetically balanced smile is close to the golden ratio.4-6 This dimensional proportion between two segments, where the length of the larger segment is 1.618 times the length of the smaller segment, is frequently found in nature.4,5,7 Some people have a shorter mesiodistal dimension of the upper lateral incisor in one or both upper dental arches, resulting in a disproportionality with the other upper anterior teeth in terms of the golden ratio.8,9 In such cases, there are two possible therapeutic approaches: recontouring the teeth to ideal dimensions10 or maintaining the original tooth dimensions, which may be perceived as unesthetic.2 Orthodontic movement could be indicated in either case.

While trained and attentive people are able to detect whether a smile is asymmetrical or out of balance,11 smile perception is not the same for everyone. Dentists and laypeople have been shown to have different perceptions of attractiveness for the same smiles.2,8 Laypeople are usually able to perceive only gross smile alterations,12,13 such as missing teeth or a severe malocclusion, while dentists are capable of identifying more subtle smile alterations.2

The goal of the present study was to evaluate perceived smile attractiveness by orthodontists, general dentists, and laypeople when there are unilateral and bilateral variations in the mesiodistal dimensions of the upper lateral incisors.

Materials and Methods

Five patients—one male and four female, with a mean age of 20.4—were randomly selected from the postgraduate orthodontic clinic at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora. The selected individuals all displayed good overall health, without any diagnosed systemic anomalies, and had all their permanent teeth except for the third molars. Their teeth were healthy and had no restorations or evident wear of the crowns. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora; each participant signed an informed-consent form.

The post-treatment records of all patients included casts without Bolton discrepancies, as evaluated with an electronic caliper,* and frontal smile photographs without evident asymmetries. The golden ratios between the visible mesiodistal widths of the central incisors, lateral incisors, and canines were measured using CorelDRAW** for Windows. Analysis of the Bolton discrepancies and the golden ratios were performed twice each by two examiners at a 20-day interval.

Three frontal photographs of the lower facial third in a natural smile were taken of each subject, using a 13MP EOS XSi*** camera with a 100mm macro lens, 1/100-second shutter speed, and f/2.8 aperture, positioned 1m in front of the subject with the lens at the height of the occlusal plane. Subjects were seated in an upright position with their arms hanging by their sides, looking directly at the reflection of their own eyes in a mirror placed 2m in front of them.14 The researchers selected the best of the three images for each subject, based on contrast, brightness, sharpness, and definition.

The visible mesiodistal widths of the upper lateral incisors were manipulated in each photograph using Photoshop,† first to achieve unilateral reductions of .5mm, 1mm, 1.5mm, and 2mm on the right side (Fig. 1) and then to produce symmetrical bilateral reductions of the same amounts (Fig. 2). These crown-width variations were applied symmetrically to the mesial and distal surfaces of each lateral incisor, with no alteration in the gingivo-incisal direction. The spaces created in the images were filled in mesially so as to leave no diastemas.

Fig. 1 A. Original smile. B. .5mm unilateral reduction in mesiodistal width of upper right lateral incisor. C. 1mm unilateral reduction. D. 1.5mm unilateral reduction. E. 2mm unilateral reduction.

Fig. 2 A. Original smile. B. .5mm bilateral reduction in mesiodistal widths of upper lateral incisors. C. 1mm bilateral reduction. D. 1.5mm bilateral reduction. E. 2mm bilateral reduction.

Two sets of printed images were created from each smile: one including the original photo and the four manipulated images with unilateral variations, and the other including the original photo and the four manipulated images with bilateral variations. All images were printed at 10cm × 15cm and 600dpi, using Fujifilm‡ inkjet photo paper in a Laserjet Pro†† printer. The lengths of the upper central incisors in the photographs were compared against the corresponding casts with an electronic caliper to ensure that the prints were life-size. Each image was then encoded and identified on the back so that only the researchers could identify it.

The images were analyzed for smile attractiveness by 90 evaluators who were unaware of the study methodology:

Group 1: 30 orthodontists (18 male, 12 female; mean age 44.3)

Group 2: 30 general dentists (17 male, 13 female; mean age 39.8)

Group 3: 30 laypeople older than 18 (15 male, 15 female; mean age 36.6)

The sample size (the number of smiles and examiners in each group) was based on previously published esthetic evaluations of smile photographs.2,10,15 Individuals in groups 1 and 2 all had at least three years of professional experience.

Each set of five images was shuffled and shown separately to each evaluator, who rated the images according to smile attractiveness, with 1 being the most attractive and 5 the least attractive. The level of attractiveness for each set was determined by the order of ranking for each evaluator. If two or more smiles were considered equally attractive and thus received the same ranking, the level of attractiveness was determined by the arithmetic average of the occupied position and the subsequent unoccupied position(s). Thus, if three images ranked second, their assigned level of attractiveness would be 3—the average of the occupied position (2) and the subsequent unoccupied positions (3 and 4).

SPSS‡‡ for macOS was used for statistical analysis. The Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance was used to evaluate the correlation between the crown-width variations of the upper lateral incisors and the smile attractiveness levels according to each group of evaluators. Statistical significance of the inter- and intragroup correlations was determined by the nonparametric chi-squared test, at a significance level of .05.

Results

Intra- and interexaminer agreement of the measurements of mesiodistal crown widths, as determined by the intraclass correlation coefficient, were .999 and .998 for the casts and .998 and .997 for the photographs, respectively, demonstrating excellent agreement.

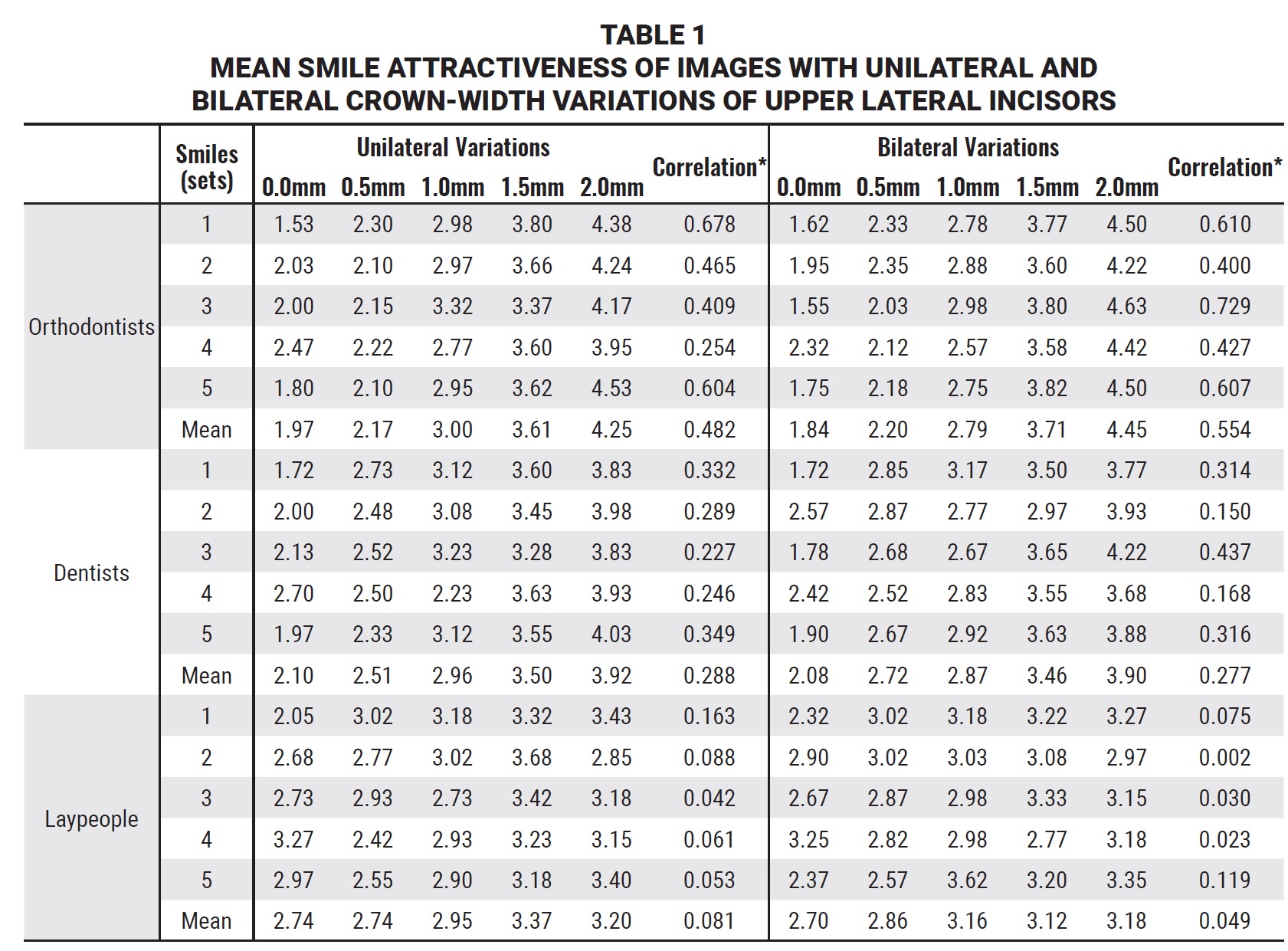

Table 1 shows the smile attractiveness levels as evaluated by the groups of orthodontists, dentists, and laypeople, along with their correlation with the amount of crown-width variation of the upper lateral incisors.

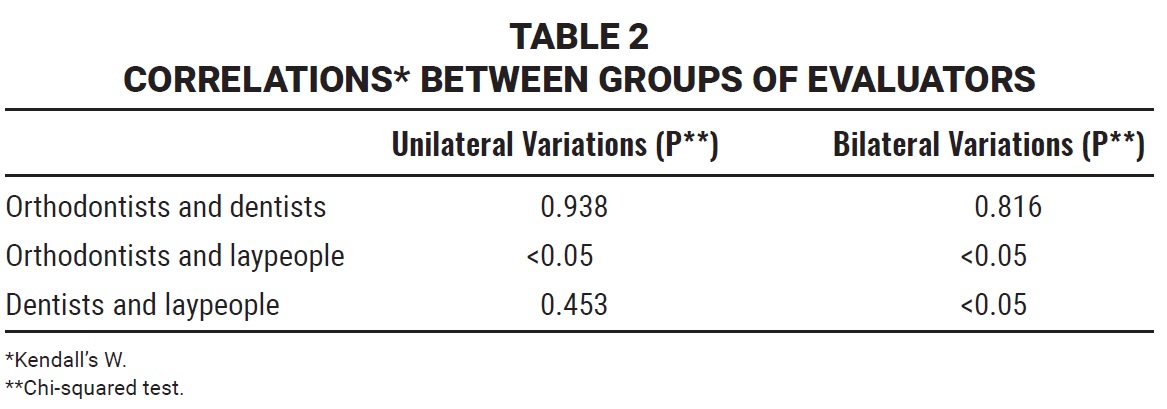

There were statistically significant differences in the unilateral rankings between the groups of orthodontists and laypeople, as well as in the bilateral rankings between the laypeople and both the orthodontists and dentists (Table 2).

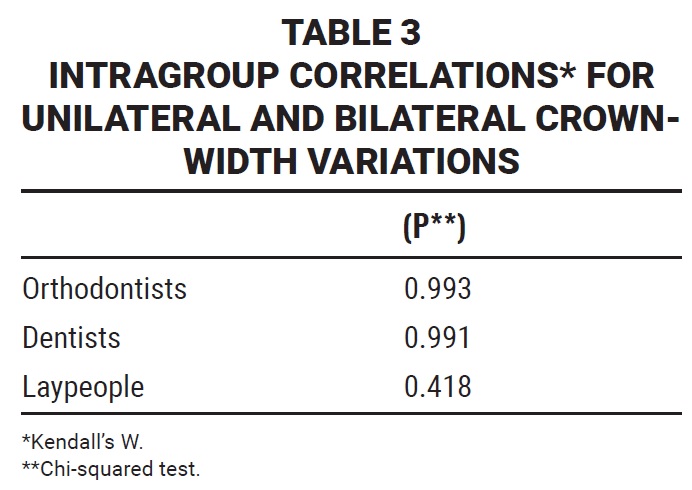

There was no statistically significant difference between the unilateral and bilateral rankings by the same groups of evaluators (Table 3).

Discussion

Although the esthetics of anterior teeth are undeniably important in the perception of smile attractiveness, alterations in tooth widths tend to be perceived differently by different individuals.2 Some previous studies have used pictures of models with ideal smiles for such evaluations,8 but Almeida and colleagues recommended using life-size frontal smile photographs, as was done in the present study, to avoid over- or undervaluation of smile esthetics.16 While some authors have employed a visual analog scale for their ratings,2,8,15 Smith and colleagues found that human judgment is much less prone to error when using direct comparisons than when using value estimations on a continuous scale.17

Previous studies have evaluated whether laypeople and dentists from various specialties would have different perceptions of smile esthetics when considering factors such as the level of maxillary incisal edges16; treatment options for missing lateral incisors8; incisor crown length, width, and angulation2; anterior gingival features10,15; and different malocclusions.12 The influence of crown-width alterations of the upper lateral incisors has previously been studied,2,18,19 but none of the authors considered the golden ratio between upper anterior teeth when choosing the initial images, thus ignoring this natural geometric ratio.4,5,7

In our study, smaller variations of lateral incisor crown width were generally ranked as more attractive than larger variations. Orthodontists exhibited the most accurate perception of smile esthetics, followed by dentists, although there was no statistically significant difference between orthodontists and dentists in terms of unilateral and bilateral mesiodistal variations. This corroborates other studies comparing dentists from different specialties10,15,16 or orthodontists and dentists,2,8,9 indicating that all dentists are trained to perceive alterations of smile esthetics in a similar manner. As in our research, Thomas and colleagues found that orthodontists were more critical than dentists in evaluating crown-width alterations of the upper lateral incisors,19 with both groups having similar professional experience as the participants in our study.

When comparing dentists and orthodontists with laypeople, there was a significant difference in every tested scenario, except between dentists and laypeople in cases with unilateral variations. This demonstrates that dentists (orthodontists or otherwise) are generally more capable than laypeople of noticing this effect on smile esthetics. Similarly, Kokich and colleagues observed that dentists could identify smaller reductions in lateral incisor crown width than laypeople could.2 Machado and colleagues reported a nonsignificant difference in esthetic perception between dentists, laypeople, and orthodontic patients when considering symmetrical variations in incisal and gingival exposure during the smile.15 Although younger laypeople tend to be more critical regarding smile esthetics,20,21 the present study illustrates that laypeople are less perceptive of variations in lateral incisor width than of variations in incisal and gingival exposure during the smile, which Machado and colleagues studied.

Unilateral alterations of dental or gingival characteristics would be expected to have a greater impact than bilateral alterations on the esthetic perception of smile display.18,22,23 Nevertheless, none of our groups of evaluators found a significant distinction between unilateral and bilateral reductions of the lateral incisors, and only orthodontists considered bilateral reductions to be less esthetic.

FOOTNOTES

- *Starrett 799, Starrett, Athol, MA; www.starrett.com.

- **Graphics Suite X8, Corel Corporation, Ottawa, Canada; www.coreldraw.com.

- ***Canon, Oita, Kyushu, Japan; www.shop.usa.canon.com.

- †Photoshop CC for MacOS, Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA; www.adobe.com.

- ‡Fujifilm Holdings Corporation, Tokyo, Japan; www.fujifilm.com.

- ††Color CP1525nw, Hewlett-Packard Company, Palo Alto, CA; www.hp.com.

- ‡‡IBM SPSS Statistics v. 24 for MacOs, Armonk, NY; www.IBM.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eli, I.; Bar-Tal, Y.; and Kostovetzki, I.: At first glance: Social meanings of dental appearance, J. Public Health Dent. 61:150-154, 2001.

- 2. Kokich, V.O. Jr.; Kiyak, H.A.; and Shapiro, P.A.: Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics, J. Esth. Dent. 11:311-324, 1999.

- 3. Thompson, L.A.; Malmberg, J.; Goodell, N.K.; and Boring, R.L.: The distribution of attention across a talker’s face, Discourse Process. 38:145-168, 2004.

- 4. Levin, E.I.: Dental esthetics and the golden proportion, J. Prosth. Dent. 40:244-252, 1978.

- 5. Lombardi, R.E.: The principles of visual perception and their clinical application to denture esthetics, J. Prosth. Dent. 29:358-382, 1973.

- 6. Bolton, W.A.: Disharmony in tooth size and its relation to the analysis and treatment of malocclusion, Angle. Orthod. 28:113-130, 1958.

- 7. Javaheri, D.S. and Shahnavaz, S.: Utilizing the concept of the golden proportion, Dent. Today 21:96-101, 2002.

- 8. Rosa, M.; Olimpo, A.; Fastuca, R.; and Caprioglio, A.: Perceptions of dental professionals and laypeople to altered dental esthetics in cases with congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors, Prog. Orthod. 1:14-34, 2013.

- 9. Shaw, W.C.: The influence of children’s dentofacial appearance on their social attractiveness as judged by peers and lay adults, Am. J. Orthod. 79:399-415, 1981.

- 10. Feu, D.; Andrade, F.B.; Nascimento, A.P.C.; Miguel, J.A.M.; Gomes, A.A.; and Capelli Júnior, J.: Perception of changes in the gingival plane affecting smile aesthetics, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 16:68-74, 2011.

- 11. Miller, C.J.: The smile line as a guide to anterior esthetics, Dent. Clin. N. Am. 33:157-164, 1989.

- 12. Katz, R.V.: Relationships between eight orthodontic indices and an oral self-image satisfaction scale, Am. J. Orthod. 73:328-334, 1978.

- 13. Vallittu, P.K.; Vallittu, A.S.; and Lassila, V.P.: Dental aesthetics—a survey of attitudes in different groups of patients, J. Dent. 24:335-338, 1996.

- 14. Ferrario, V.F.; Sforza, C.; Miani, A.; and Tartaglia, G.: Craniofacial morphometry by photographic evaluations, Am. J. Orthod. 103:327-337, 1993.

- 15. Machado, R.M.; Assad Duarte, M.E.; Jardim da Motta, A.F.; Mucha, J.N.; and Motta, A.T.: Variations between maxillary central and lateral incisal edges and smile attractiveness, Am. J. Orthod. 150:425-435, 2016.

- 16. Almeida, R.R.; Garib, D.G.; Almeida-Pedrin, R.R.; Almeida, M.R.; Pinzan, A.; and Junqueira, M.H.Z.: Upper central interincisor diastema: When and how to intervene? Dent. Press J. Orthod. 9:137-156, 2004.

- 17. Smith, J.; Kaufman, H.; and Baldasare, J.: Direct estimation considered within a comparative judgment framework, Am. J. Psychol. 97:343-358, 1984.

- 18. Kokich, V.O.; Kokich, V.G.; and Kiyak, H.A.: Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: Asymmetric and symmetric situations, Am. J. Orthod. 130:141-151, 2006.

- 19. Thomas, M.; Reddy, R.; and Reddy, B.J.: Perception differences of altered dental esthetics by dental professionals and laypersons, Ind. J. Dent. Res., 22:242-247, 2011.

- 20. Rodrigues, C.D.T; Magnani, R.; Candido Machado, M.S.; and Oliveira, O.B.: The perception of smile attractiveness, Angle Orthod. 79:634-639, 2009.

- 21. Sriphadungporn, C. and Chamnannidiadha, N.: Perception of smile esthetics by lay people of different ages, Prog. Orthod. 18:8, 2017.

- 22. Pinho, T.; Bellot-Arcís, C.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; and Neves, M.: Esthetic assessment of the effect of gingival exposure in the smile of patients with unilateral and bilateral maxillary incisor agenesis, J. Prosthod. 24:366-372, 2015.

- 23. Betrine Ribeiro, J.; Alecrim Figueiredo, B.; and Wilson Machado, A.: Does the presence of unilateral maxillary incisor edge asymmetries influence the perception of smile esthetics? J. Esth. Restor. Dent. 29:291-297, 2017.

COMMENTS

.