CASE REPORT

Asymmetrical First Molar Extractions

Extractions are generally used to relieve moderate or severe crowding, retract protrusive incisors, or balance maxillomandibular anteroposterior discrepancies.1 The choice of which teeth to extract requires a thorough evaluation of the patient’s dentition, considering treatment goals1,2 along with dental and periodontal characteristics.3,4 The teeth most commonly indicated for extraction are, in decreasing order, the first premolars, lower incisors, second premolars, first molars, and canines.3

First premolars are preferred for extraction because of their location and mesiodistal crown diameter, since the space can be promptly utilized to facilitate orthodontic biomechanics for alignment and retraction of the anterior teeth.5 On the other hand, first molars are the permanent teeth that tend to show the most structural damage, as the first permanent teeth to erupt and the most posterior in position.6,7 First molars with extensive tissue loss can sometimes be the best option for extraction,8,9 especially in cases with significant crowding, even though extraction of first permanent molars usually results in more complex orthodontic treatment.4

In extraction cases with asymmetrical structural impairment of the first permanent molars, asymmetrical extractions can be a viable option, despite the difficulty involved in closing the remaining spaces and the need for efficient anchorage control.7,10,11 This case report describes the treatment of an adult patient using an asymmetrical extraction pattern.

Similar articles from the archive:

Diagnosis and Treatment Plan

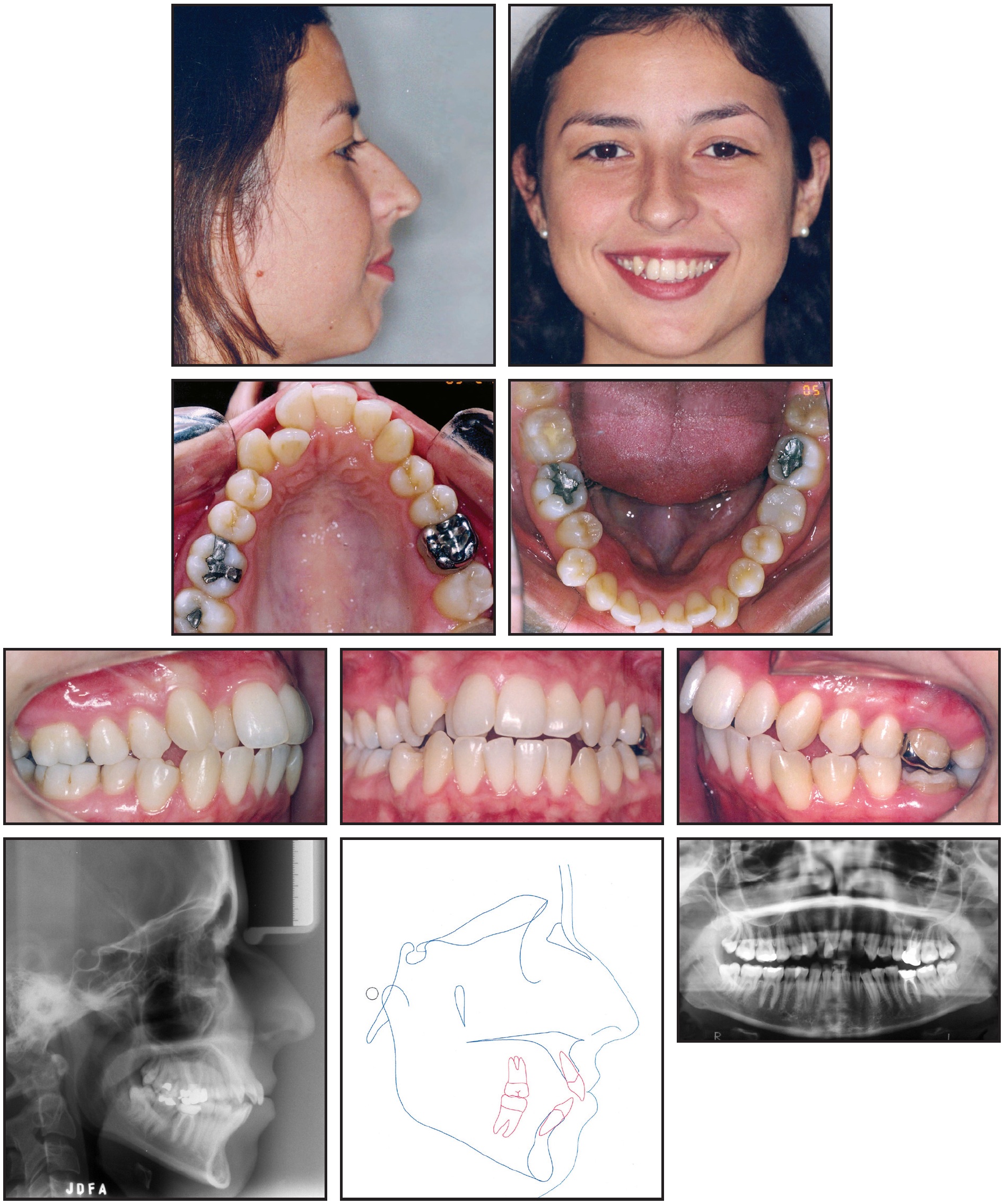

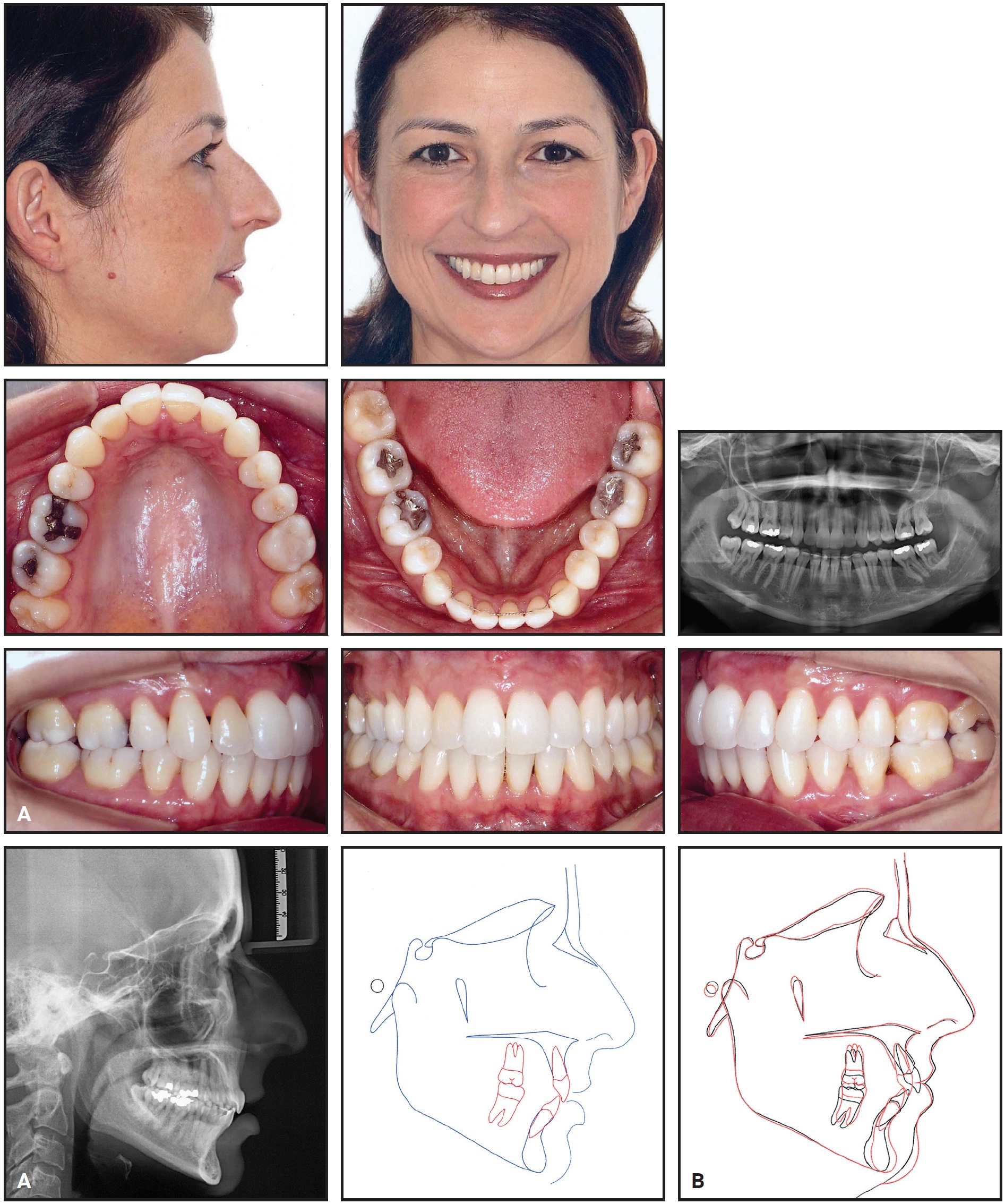

A 22-year-old female presented with the chief complaints of dental crowding, protrusive incisors, and a lack of passive lip seal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 22-year-old female patient with Class II, division 1 malocclusion; moderate crowding; protrusive incisors; and 3mm midline deviation before treatment.

The upper anterior region was contracted, the upper right lateral incisor was in crossbite, and moderate crowding was noted. The patient had a 3mm midline deviation to the right, with a dental discrepancy of −8mm in the upper arch and −6.5mm in the lower arch and a Class II, division 1 malocclusion. Extensive crown restorations were present on the upper and lower left first molars; the upper molar needed endodontic retreatment, and the lower one required a full crown restoration.

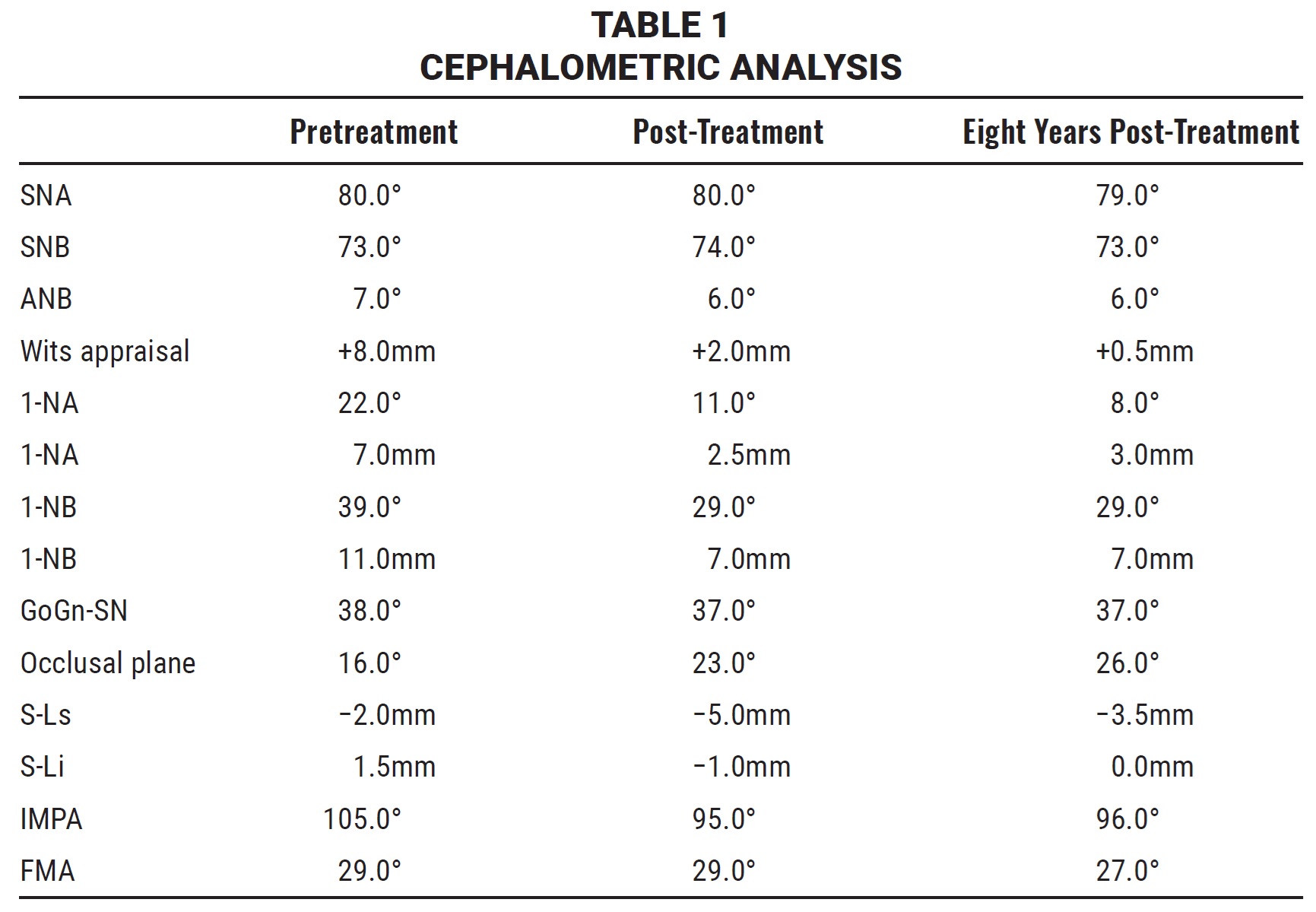

Cephalometric analysis (Table 1) indicated a skeletal Class II relationship (ANB = 7°; Wits appraisal = +8mm) with protrusive lower incisors (1-NB = 39°; IMPA = 105°) and a vertical growth pattern (GoGn-SN = 38°; FMA = 29°).

Orthodontic treatment goals were to level and align the teeth, reduce the protrusion of both upper and lower incisors, and establish disclusion guidance. The extraction of four teeth (one in each quadrant) would be required to gain enough space. Since the left first molars presented with extensive structural damage and needed endodontic and prosthetic treatment, while the left third molars showed acceptable morphological conditions, the upper and lower left first molars were extracted along with the upper and lower right first premolars.

Treatment Progress

An .022" × .030" preadjusted edgewise appliance was placed for 16 months of leveling and alignment. After 13 months of treatment, the required space had been gained, and correction of the upper right lateral incisor crossbite was initiated using an .018" stainless steel archwire with two boot loops positioned mesial and distal to the incisor. A posterior acrylic bite plate supported by the upper molars and premolars was placed for 10 days to disclude the anterior teeth.

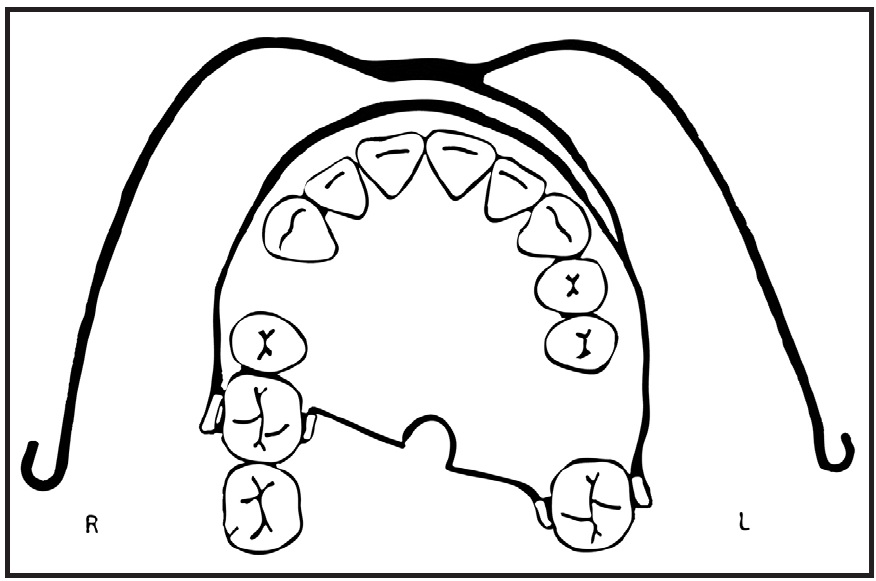

Portions of two headgears were combined to create an asymmetrical extraoral device delivering 300g of force on each side (Fig. 2). The inner bow was cut away from one headgear, and the right arm of the inner bow was removed from a second headgear. The first inner bow was then soldered to the left arm of the second headgear’s inner bow. A transpalatal bar was added to stabilize the upper and lower molars during distalization of the canines and left premolars and retraction of the incisors; both the headgear and the transpalatal bar were supported by the upper right first molar and upper left second molar. The headgear was worn for about 12 hours each night for 10 months. Thereafter, Class II elastics were worn 24 hours per day for 10 months on the right side and 14 months on the left.

Proper alignment was achieved within 25 months of treatment, but a black triangle was noticed in the region of the interdental papilla between the upper left lateral incisor and canine. To improve both esthetic and functional conditions, the incisor was reduced by .5mm on the distal aspect, thus shortening the distance between the contact point and the marginal bone crest and allowing the space to be filled by the gingival papilla.12

Fig. 2 After extraction of both left first molars and both right first premolars, asymmetrical headgear fabricated by soldering inner bow of one headgear to outer bow and left inner bow of another headgear. Transpalatal bar used to stabilize upper and lower molars during distalization and retraction.

Treatment Results

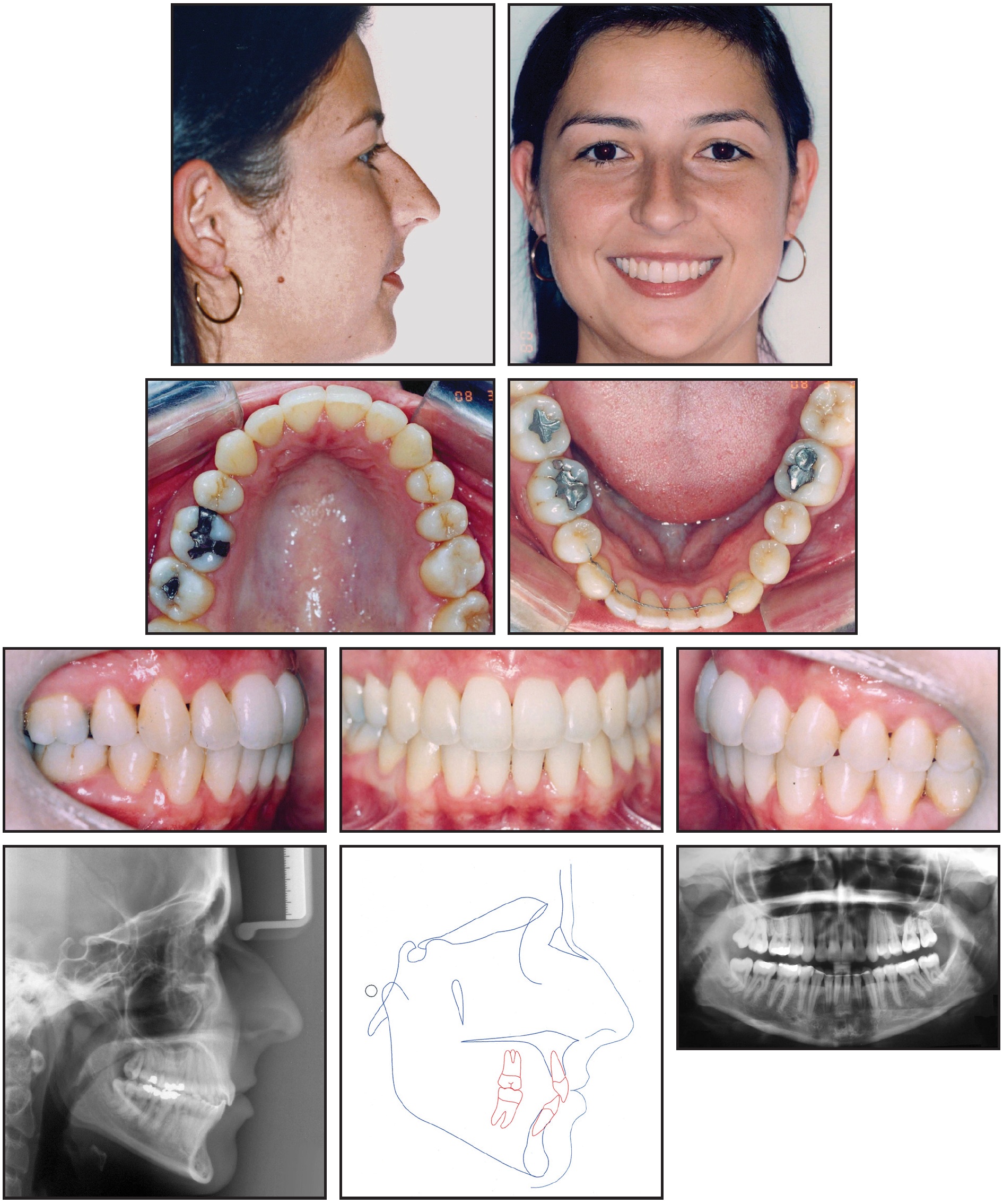

Total treatment time was 47 months (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Patient after 47 months of treatment.

The lower incisor protrusion was reduced by 4mm (Table 1), requiring a compensatory retraction of the upper incisors (4.5mm) to achieve a passive lip seal. Class I molar and canine relationships were achieved, and the upper and lower dental midlines were coincident. The left second molars were moved mesially, which allowed better positioning of the left third molars. The anteroposterior and vertical skeletal cephalometric measurements remained constant, with the exception of the Wits analysis, which was reduced by 6mm as a result of the increased inclination of the occlusal plane.

A retainer made of .018" twist-flex wire was bonded to the lower anterior teeth, and an upper removable retainer was prescribed to be worn 24 hours per day for one year and 12 hours per day for another year. Eight years after debonding, no clinically significant changes were noted in tooth positioning (Fig. 4, Table 1). Proximal contact of the left second premolars and second molars was stable despite the lack of fixed retention, and no interference was noted in the disclusion guidance.

Fig. 4 A. Patient eight years after treatment. B. Superimposition of cephalometric tracings before treatment and eight years after treatment.

Discussion

When arch space is needed and the first molars require extraction or extensive restoration, removal of the first molars is preferable to the extraction of healthy premolars.4,13 In the case presented here, moderate crowding in both arches, a dental midline deviation, protrusive incisors, and an unfavorable profile required the extraction of four teeth—one in each quadrant—and incisor retraction. The need for extensive restoration and endodontic retreatment of the left first molars, along with the acceptable morphology of the left third molars, justified the unusual choice of an asymmetrical extraction pattern involving two first molars on one side and two first premolars on the other.4,7,10

Extraction of first permanent molars usually leads to more extended and complex treatment,4 with a tendency toward marked mesiolingual inclination of the lower second molars.7 In our case, the lower left second and third molars underwent extensive mesial movement without significant mesial inclination, resulting in a more favorable position of the third molars relative to the anterior border of the mandibular ramus. A classic clinical effect linked to first molar extraction, attributable to the mesial movement of the second and third molars, is a counterclockwise mandibular rotation with closure of the mandibular plane.14 Our patient did not show any significant alteration in mandibular plane inclination, possibly because the first molars were extracted on only one side.

Another aspect of treatment involving upper first-molar extractions is the need for reinforced anchorage in the upper arch,4,7,11 particularly in cases of pronounced incisor protrusion and anterior dental crowding,7 as seen in our patient. This situation can be addressed with appliances for either reinforced anchorage10 or skeletal anchorage.15-17 Our use of a transpalatal bar and headgear, followed by Class II elastics, allowed distalization of the premolars and canines, dental alignment, and upper incisor retraction to take place without interference from excessive mesial migration of the left second and third molars. The incisor retraction also resulted in an esthetic posterior repositioning of the upper and lower lips and an improved passive lip seal.18

In treatment involving asymmetrical extractions, the difference in space obtained on the right and left sides can cause a midline deviation.4 In this case, even though the upper dental midline was deviated opposite to the side of the first molar extractions, the patient’s compliance with the asymmetrical headgear ensured enough anchorage support to correct the deviation. This demonstrates the importance of cooperation in cases where anchorage reinforcement is used instead of mini-implants.

REFERENCES

- 1. Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.W. Jr.; and Sarver, D.M.: Contemporary Orthodontics, 4th ed., Mosby, St. Louis, 2007.

- 2. Lim, H.J.; Ko, K.T.; and Hwang, H.S.: Esthetic impact of premolar extraction and nonextraction treatments on Korean borderline patients, Am. J. Orthod. 133:524-531, 2008.

- 3. Chung, K.R.; Choo, H.; Lee, J.H.; and Kim, S.H.: Atypical orthodontic extraction pattern managed by differential en-masse retraction against a temporary skeletal anchorage device in the treatment of bimaxillary protrusion, Am. J. Orthod. 140:423-432, 2011.

- 4. Ong, D.C. and Bleakley, J.E.: Compromised first permanent molars: An orthodontic perspective, Austral. Dent. J. 55:2-14, 2010.

- 5. Graber, T.M.: Maxillofacial orthopedics—A clinical approach for the growing child, Am. J. Orthod. 87:170, 1985.

- 6. Moyers, R.E.: Handbook of Orthodontics, 4th ed., Year Book Medical Publishers, Chicago, 1988.

- 7. Sanders, D.A.; Rigali, P.H.; Neace, W.P.; Uribe, F.; and Nanda, R.: Skeletal and dental asymmetries in Class II subdivision malocclusions using cone-beam computed tomography, Am. J. Orthod. 138:542.e1-20, 2010.

- 8. Munoz, A.: Correction of a Class II deep overbite skeletal and dental asymmetric malocclusion in an adult patient, Am. J. Orthod. 127:611-617, 2005.

- 9. Liu, R.; Xiaoqing, M.; Wamalwa, P.; and Zou, S.J.: Nonsurgical treatment of an adult patient with bilateral posterior crossbite, Am. J. Orthod. 140:106-114, 2011.

- 10. Schroeder, M.A.; Schroeder, D.K.; Santos, D.J.S.; and Leser, M.M.: Molars extraction in orthodontics, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 16:130-157, 2011.

- 11. Melgaço, C.A. and Araújo, M.T.S.: Asymmetric extractions in orthodontics, Dent. Press J. Orthod. 17:151-156, 2012.

- 12. Tarnow, D.P.; Magner, A.W.; and Fletcher, P.: The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla, J. Periodontol. 63:995-996, 1992.

- 13. Tayer, B.H.: The asymmetric extraction decision, Angle Orthod. 62:291-297, 1992.

- 14. Sandler, P.J.; Atkinson, R.; and Murray, A.M.: For four sixes, Am. J. Orthod. 117:418-434, 2000.

- 15. Kyung, H.M.; Park, H.S.; Bae, S.M.; Sung, J.H.; and Kim, I.B.: Development of orthodontic micro-implants for intraoral anchorage, J. Clin. Orthod. 37:321-328, 2003.

- 16. Chung, K.R.; Kim, S.H.; and Kook, Y.A.: The C-orthodontic micro-implant, J. Clin. Orthod. 38:478-486, 2004.

- 17. Galeotti, A.; Uomo, R.; Spagnuolo, G.; Paduano, S.; Cimino, R.; Valletta, R.; and D’Anto, V.: Effect of pH on in vitro biocompatibility of orthodontic miniscrew implants, Prog. Orthod. 14:15, 2013.

- 18. Kuhn, M.; Markic, G.; Doulis, I.; Göllner, P.; Patcas, R.; and Hänggi, M.P.: Effect of different incisor movements on the soft tissue profile measured in reference to a rough-surfaced palatal implant, Am. J. Orthod. 149:349-357, 2016.

COMMENTS

.