2001 JCO Orthodontic Practice Study, Part 3: Practice Growth

This final part of our report on the 2001 JCO Orthodontic Practice Study will highlight the growth that has occurred in case starts and gross income over the two years since the previous study. We will also present tables comparing practices of female orthodontists to those of male orthodontists, and practices affiliated with management service organizations to traditional practices.

The methodology of this 11th biennial survey of U.S. orthodontists was outlined in Part 1 (JCO, October 2001), which also discussed trends in orthodontic economics and practice administration during the 20 years of Practice Studies. Part 2 (JCO, November 2001) covered the factors that appear to be related to practice success in terms of net income and case starts.

Practice Growth

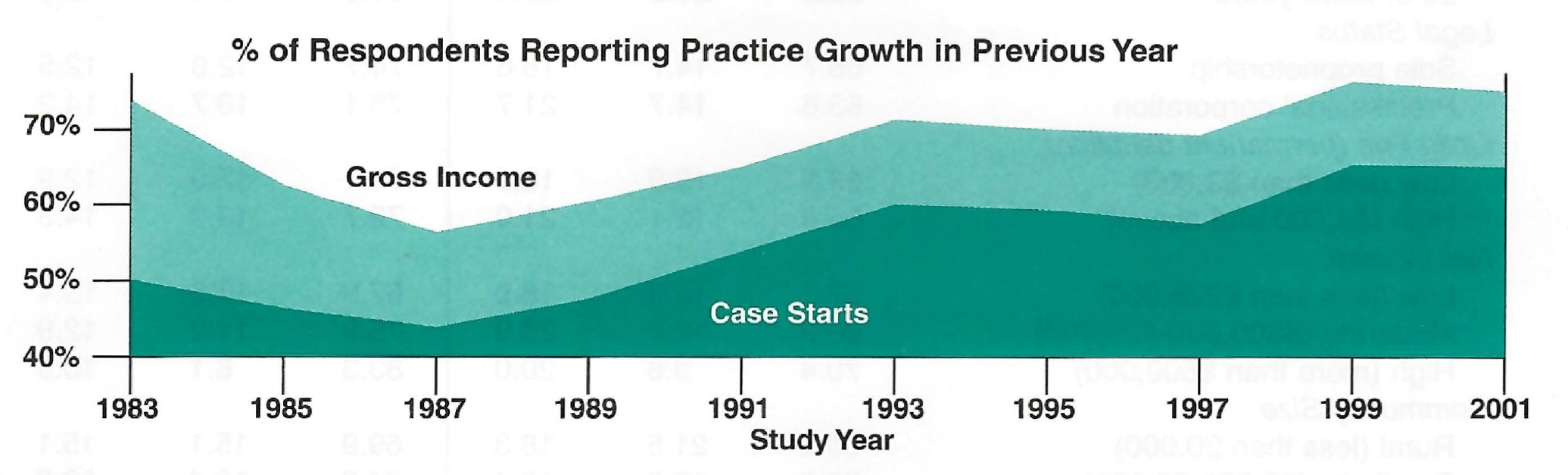

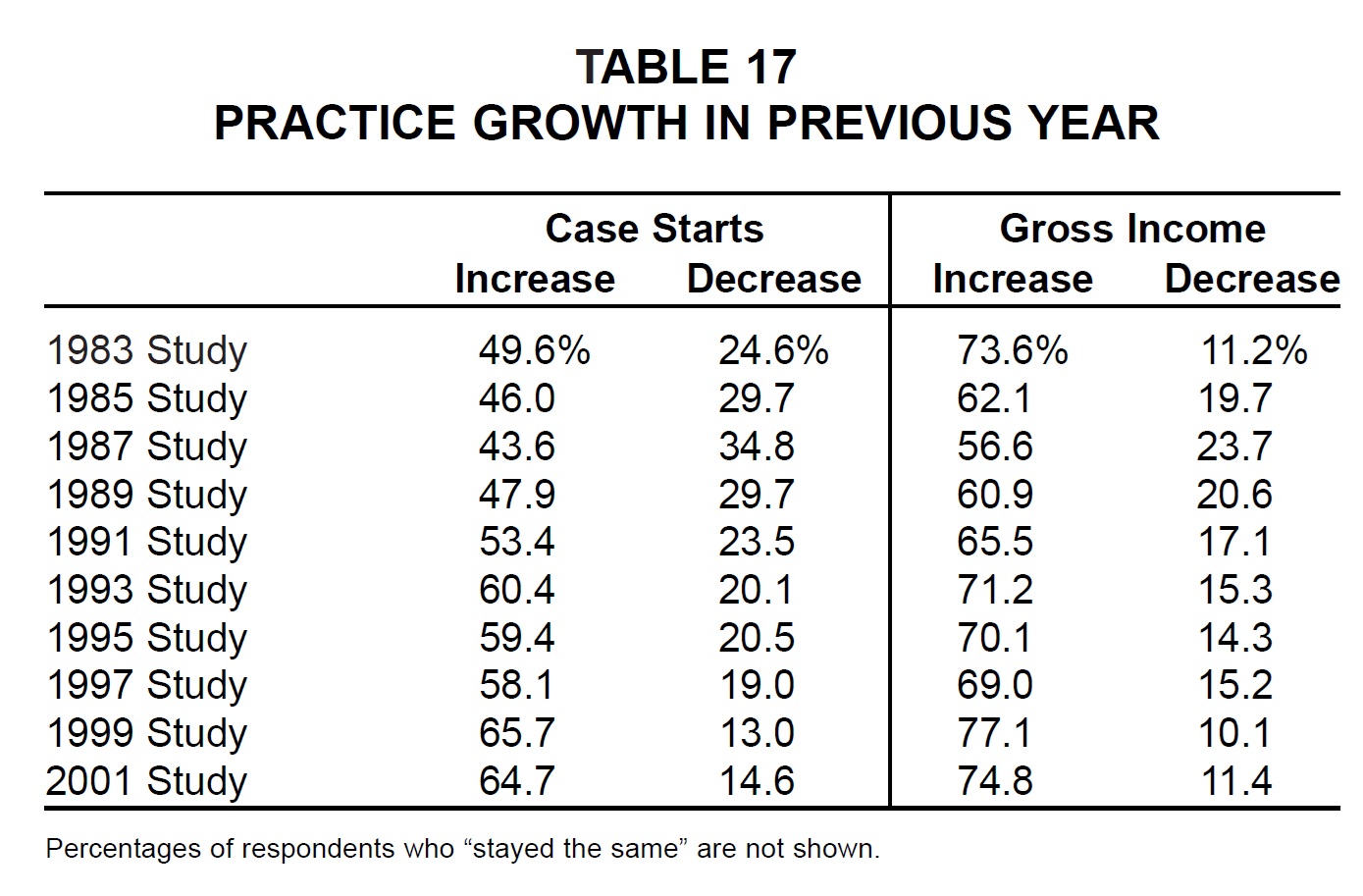

As in every survey since 1983, respondents were asked whether their practices' case starts and gross income increased, decreased, or stayed the same compared to the previous year. In the present Study, therefore, they were comparing figures from 2000 to those of 1999.

Similar articles from the archive:

The percentages of orthodontists reporting increases in case starts and gross income were the second highest ever (Fig. 6). Growth percentages were slightly behind those of the 1999 Practice Study, however, perhaps giving some sign of an impending economic downturn.

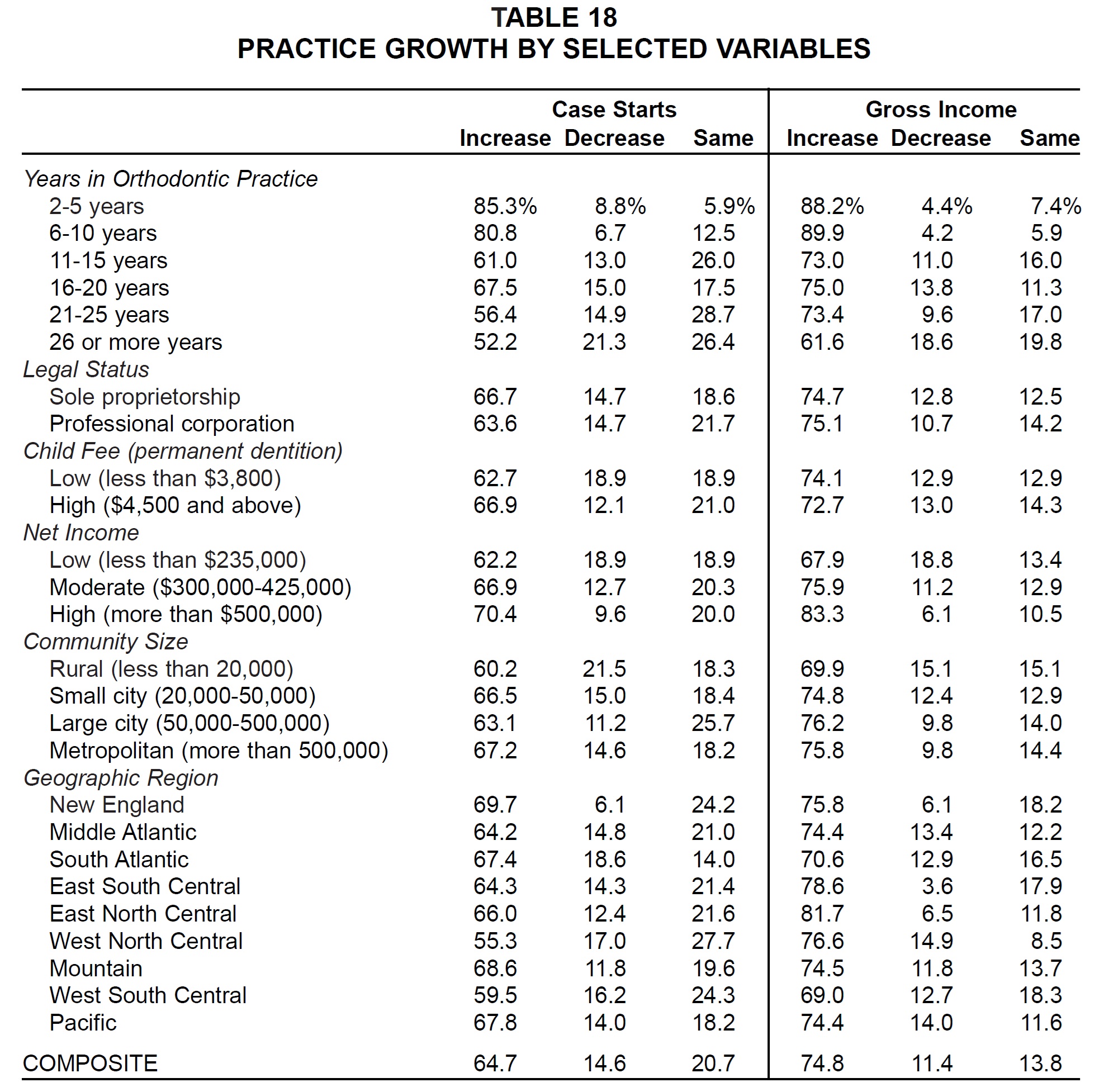

Orthodontists who had been in practice the shortest time were the most likely to be growing, as in every previous survey (Table 18). Most practice age groups showed less growth than in the 1999 Study, the exceptions being case starts for 2-to-5-year-old and 16-to-20-year-old practices. There were many more practices that stayed the same in the 11-to-15-year group compared to 1999.

The other groups that showed more growth in both case starts and net income in the 2001 Study than in the 1999 Study were low fee and low net income practices, metropolitan practices, and those in the New England, East North Central, and Pacific regions (Table 17).

Expectations for 2001

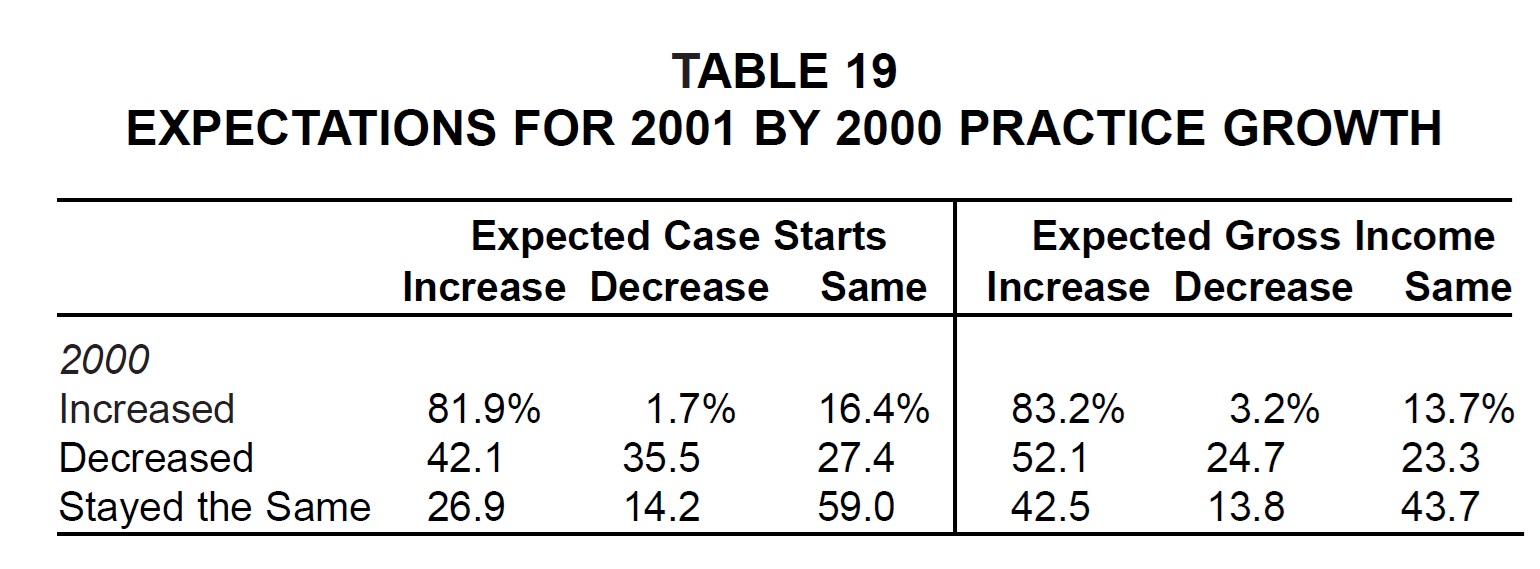

As in past reports, the respondents that reported increasing, decreasing, or staying the same in case starts or gross income in the preceding year were the most likely to predict the same results in the following year (Table 19).

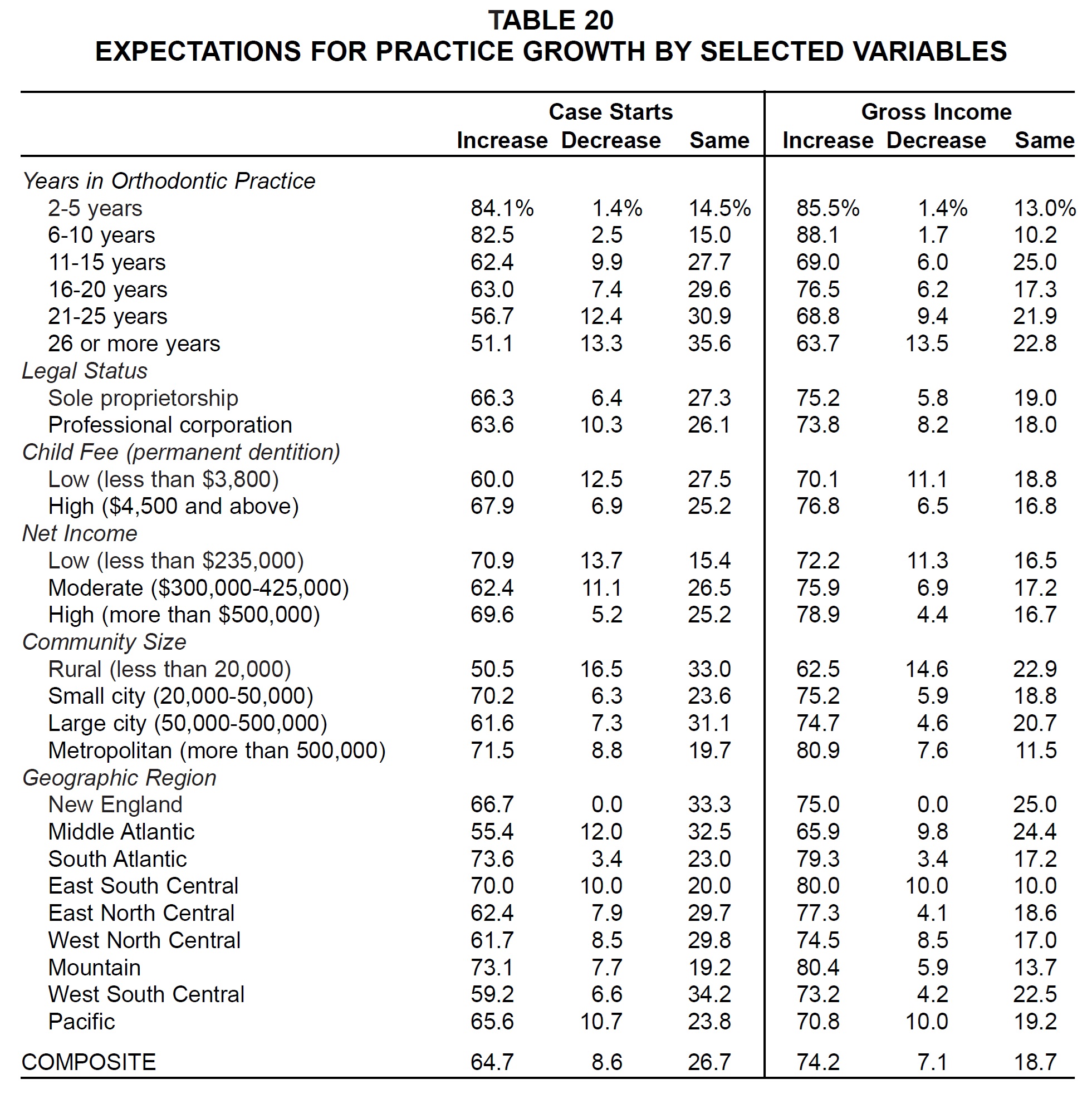

Despite the minor slowdown in growth since the 1999 Study, respondents were generally more optimistic about future growth than ever before (Table 20). The only groups that predicted less growth in both case starts and gross income for 2001 than had been predicted for 1999 were 2-to-5-year-old and 11-to-15-year-old practices and rural and West South Central orthodontists.

Reasons for Lack of Growth

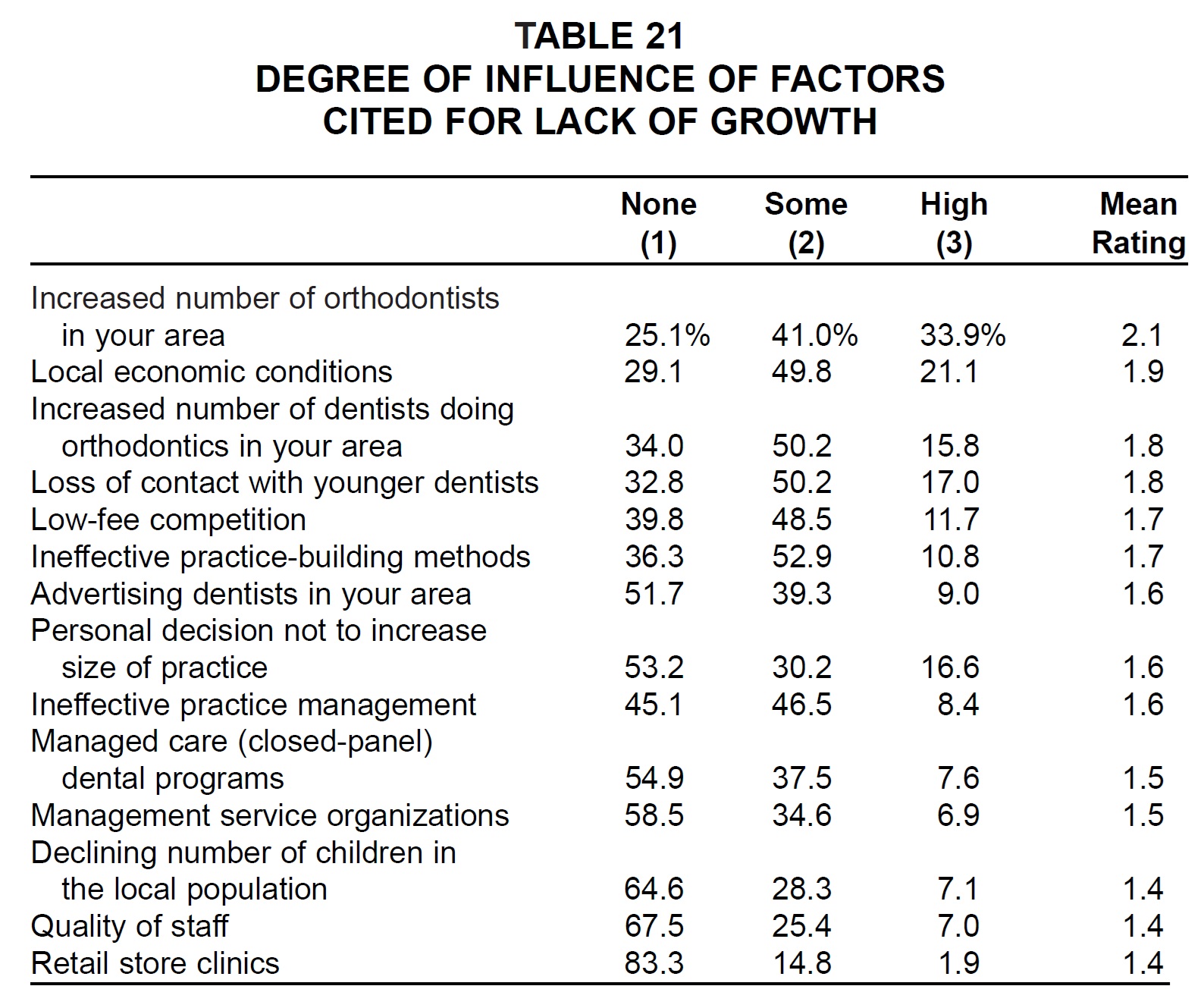

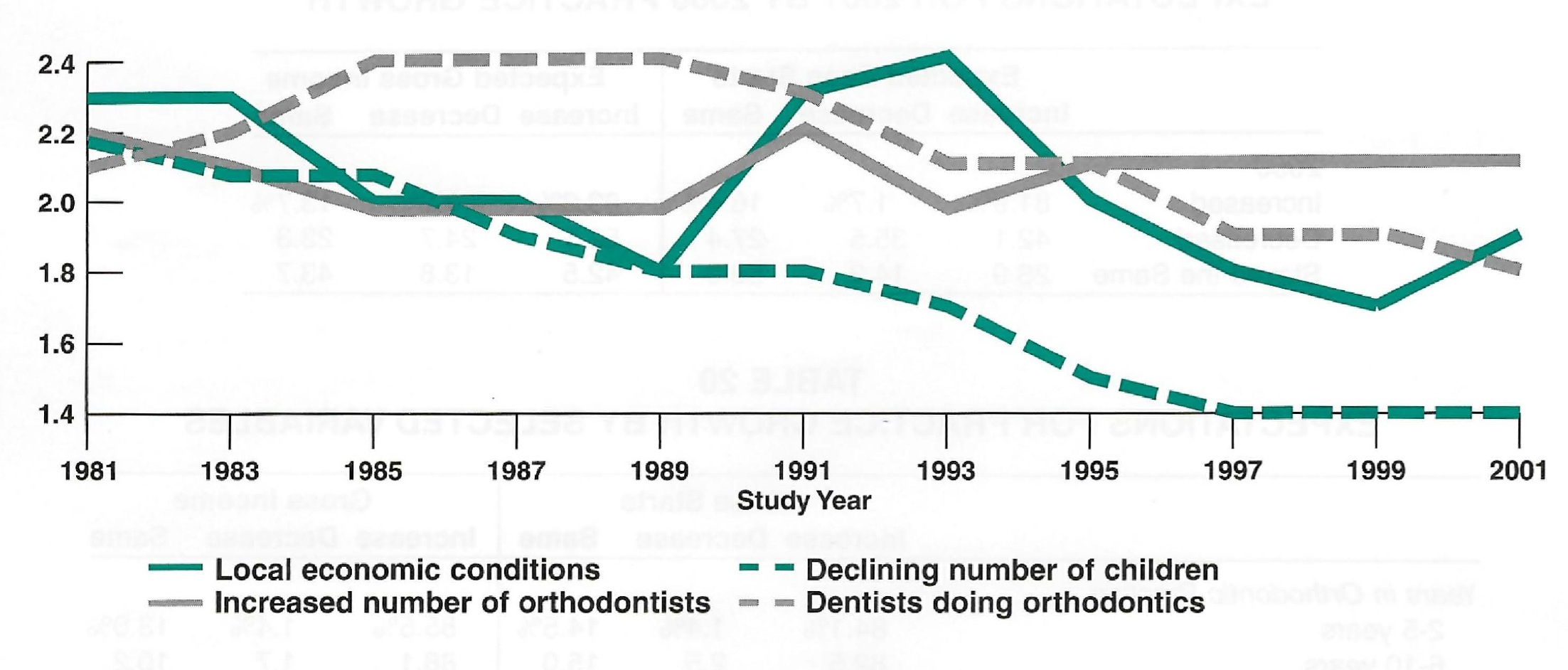

As usual, respondents who did not report increased case starts in 2000 were asked to rate the degree of influence of various factors (Table 21). Local economic conditions, which had been declining in influence since the 1993 Study, showed a slight increase from 1999. Competition from other orthodontists, general dentists, and low-fee practices was rated about the same as in the previous study. Availability of child patients, now considered a minor factor, has been showing a steady decline in influence since the first Practice Study in 1981 (Fig. 7). Managed care and management service organizations were seen to have little impact on growth.

Breakdowns by Sex of Orthodontist

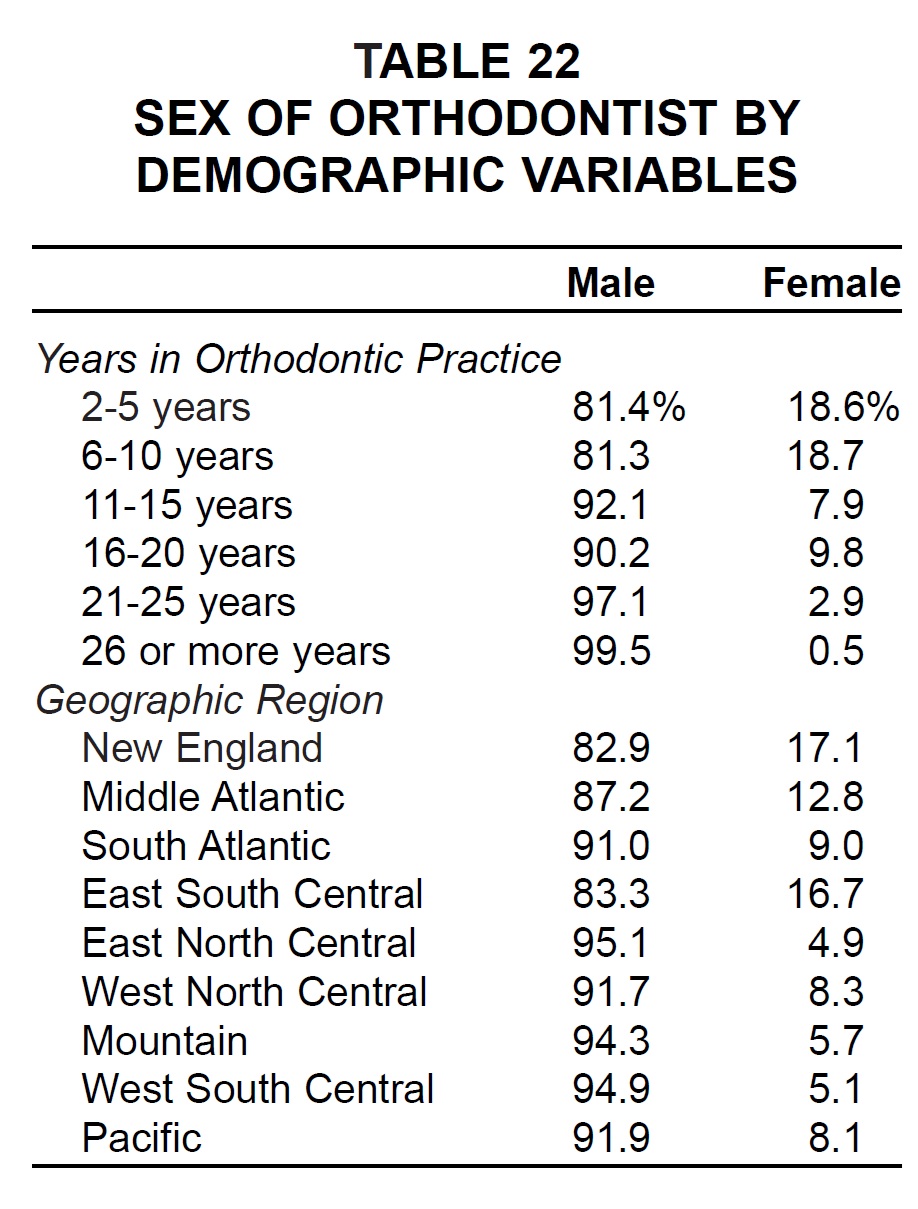

This is the second biennial report in which we have broken down selected variables for comparisons of male and female orthodontists. The percentage of female practitioners has risen gradually over the 20 years of these surveys and now stands at 8.6% overall. In fact, nearly 19% of all respondents who have been in practice 10 years or less are now female (Table 22). Geographically, higher percentages of female orthodontists were found in the East than in the West.

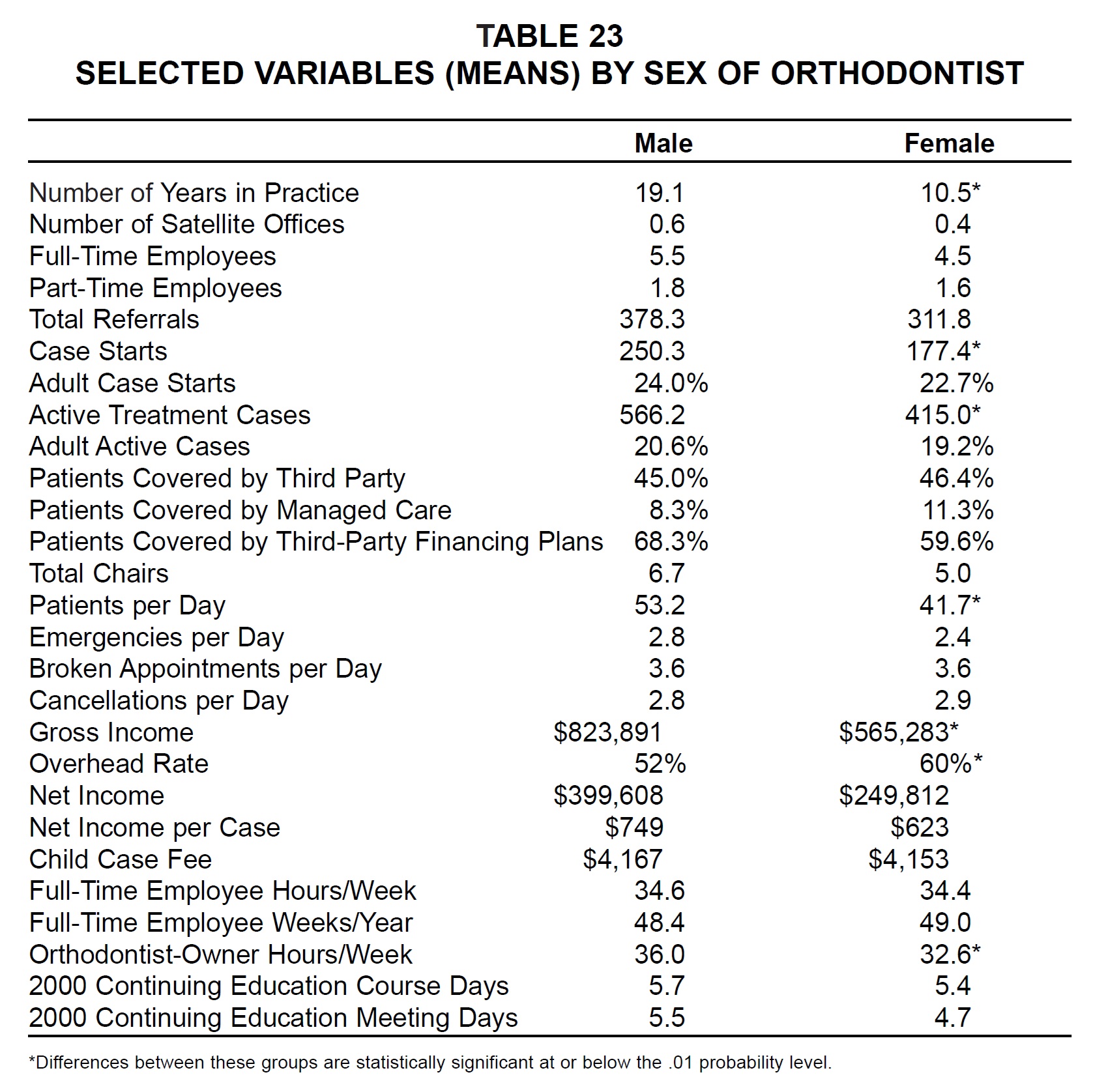

With women's practices an average 8.6 years newer than men's, there was naturally a substantial difference in practice size (Table 23). Female orthodontists had significantly higher overhead rates, although fees were about the same and net income per case was not significantly different. Women reported slightly lower percentages of adult patients, but slightly higher percentages of third-party and managed-care patients. Female respondents also reported working fewer hours per week and spending less time at courses and meetings.

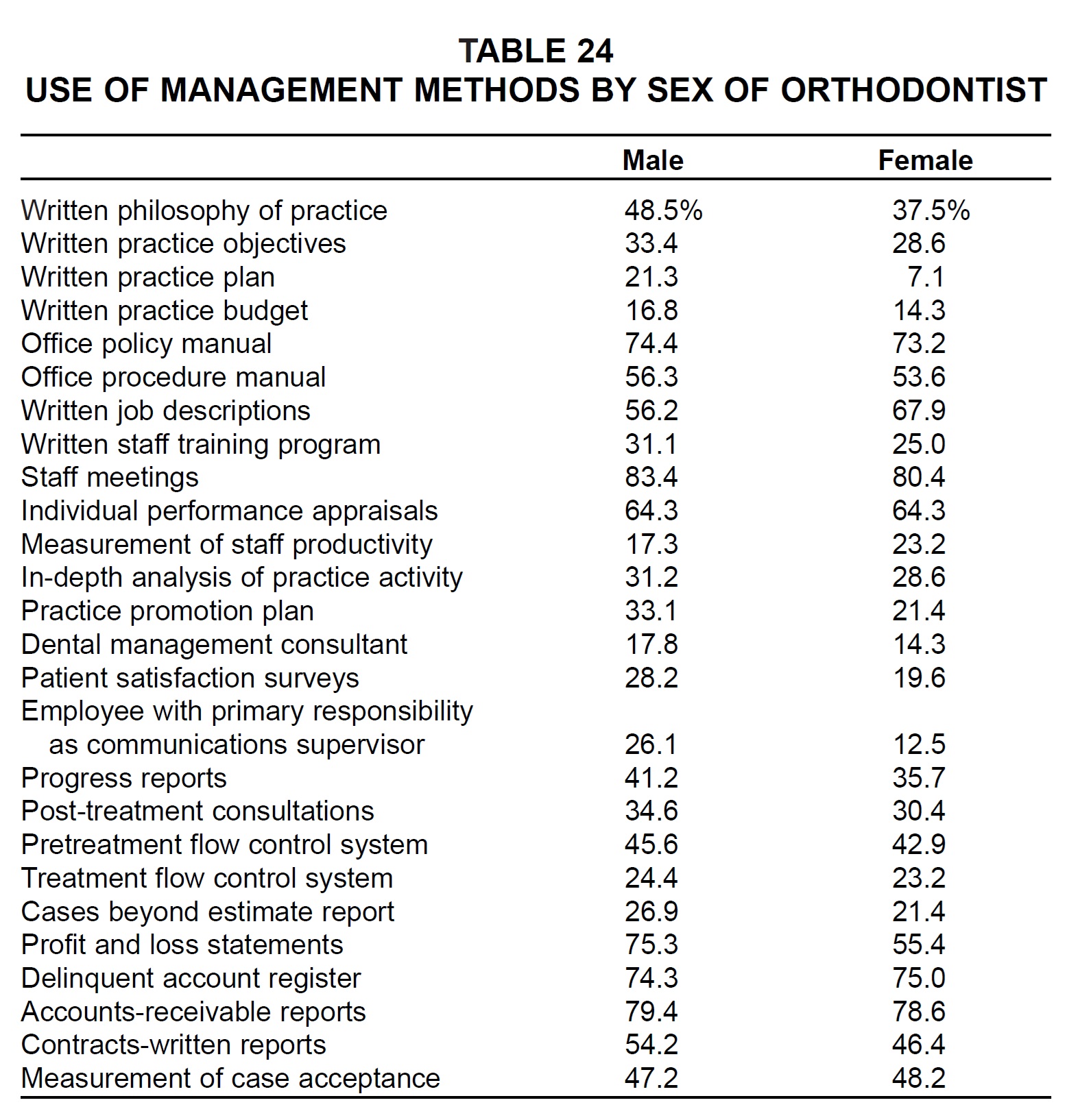

As shown in Part 2 of this series, smaller practices tend to make less use of management methods, delegation, and practice-building methods than larger practices do. The only management methods used by equal or larger percentages of female respondents than male respondents were office procedure manual, written job descriptions, individual performance appraisals, measurement of staff productivity, delinquent account register, and measurement of case acceptance (Table 24)--a similar list to that of the previous survey. As in the 1999 Study, women were less than half as likely as men to employ communications supervisors.

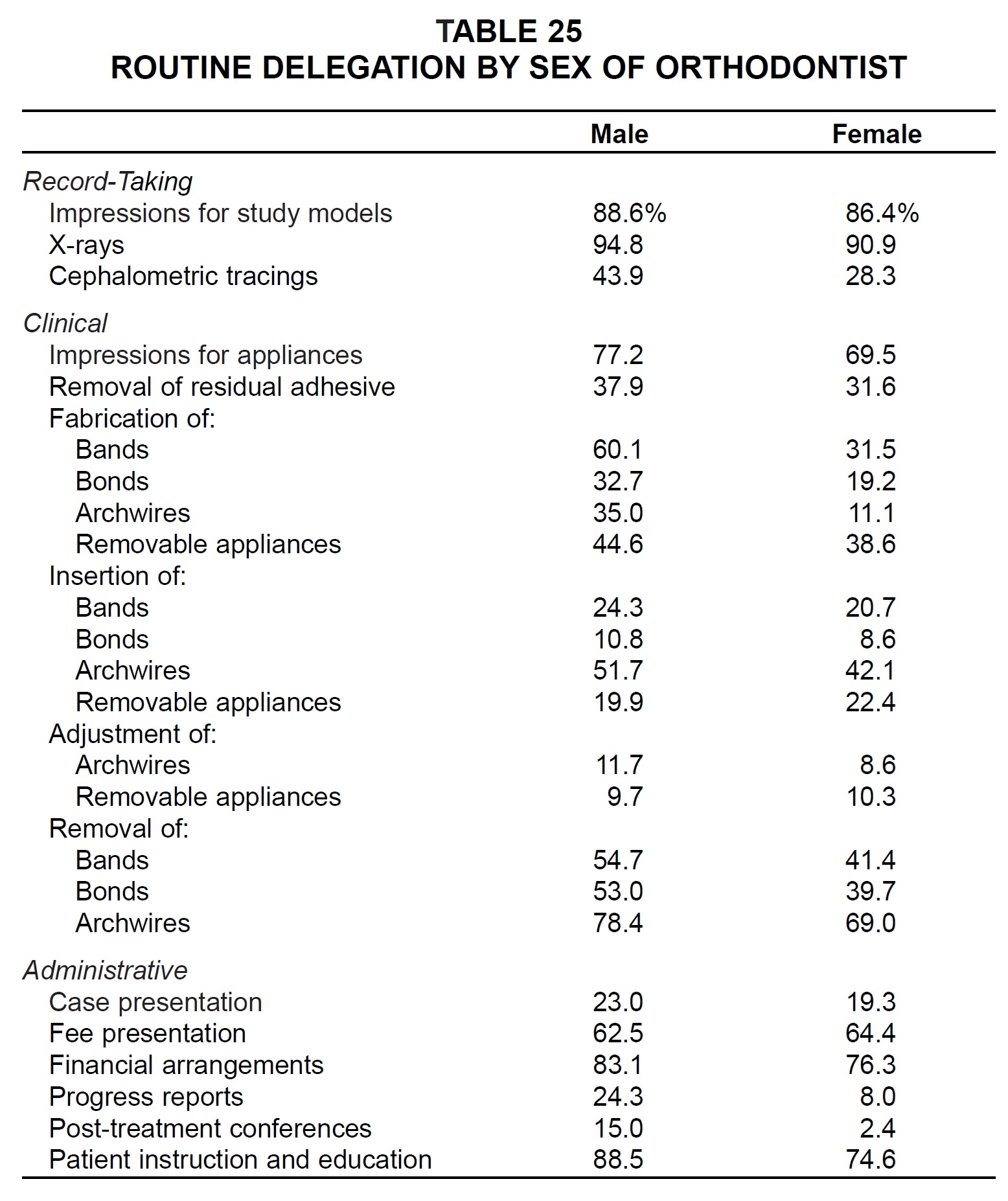

The only tasks delegated more routinely by female practitioners than by male practitioners were insertion and adjustment of removable appliances and fee presentation (Table 25). Fewer than 10% of the female respondents routinely delegated bonding, archwire adjustments, progress reports, or post-treatment conferences.

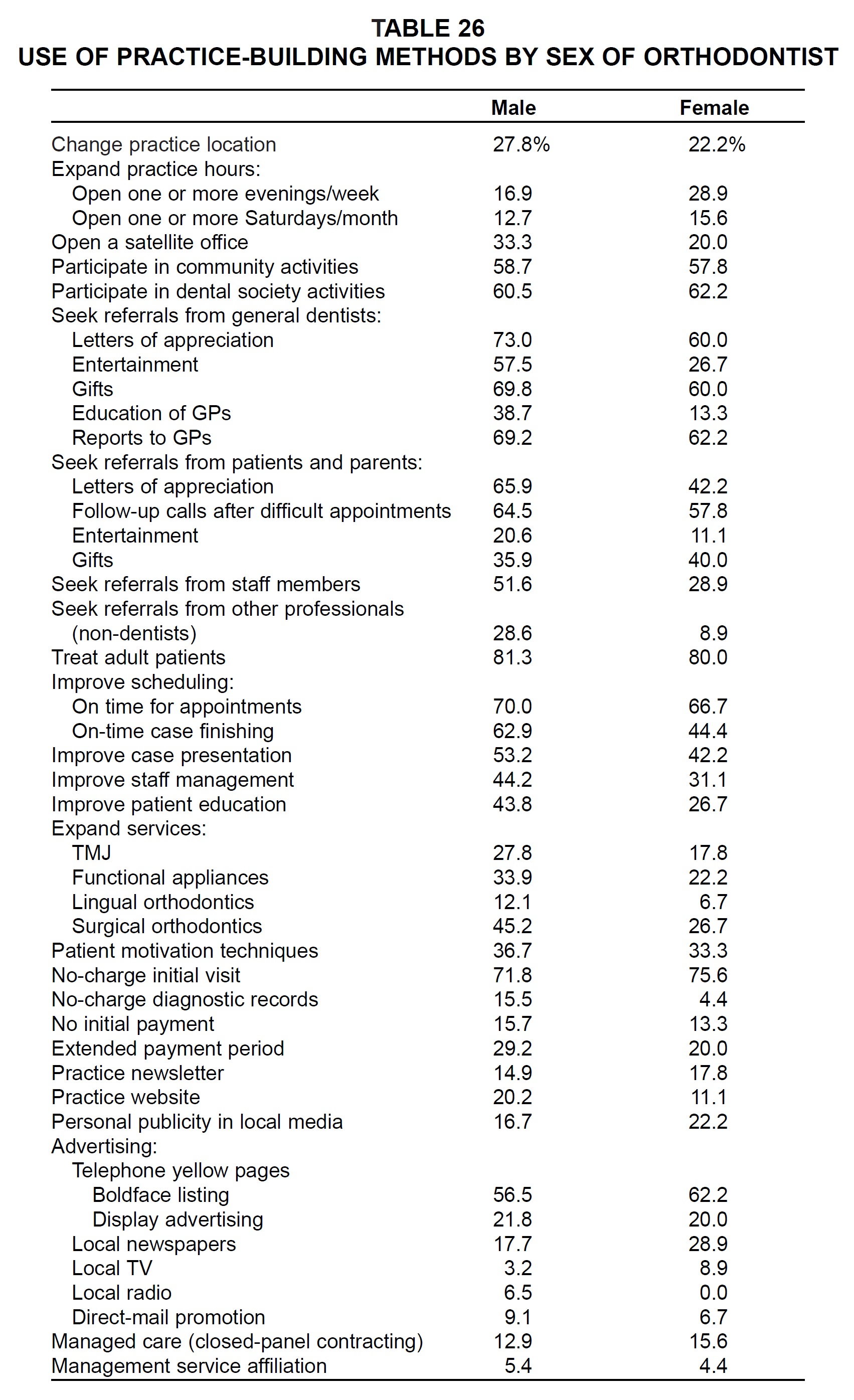

The only practice-building methods used more by women than by men were: expand practice hours; participate in dental society activities; gifts to patients and parents; no-charge initial visit; practice newsletter; personal publicity in local media; advertising by yellow pages boldface listing, newspaper, and TV; and managed care (Table 26).

Management Service Organizations

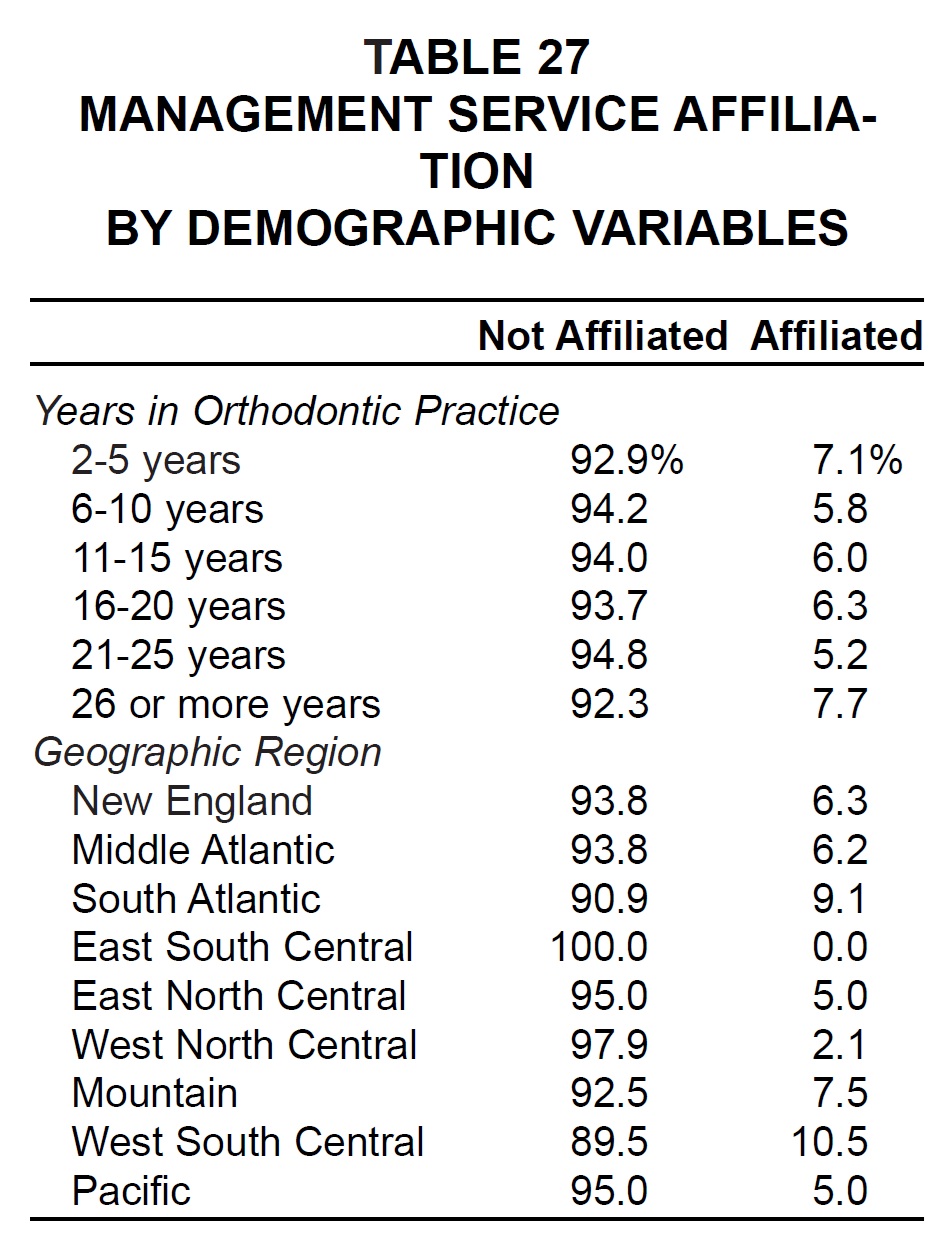

Only 6.3% of the single-owner practices included in this survey were affiliated with management service organizations--down from 9.8% in 1999. The MSO affiliates were much more evenly distributed by years in practice than in 1999, when they tended to be older (Table 27). The highest percentages of MSO affiliates were again found in the Mountain and West South Central regions.

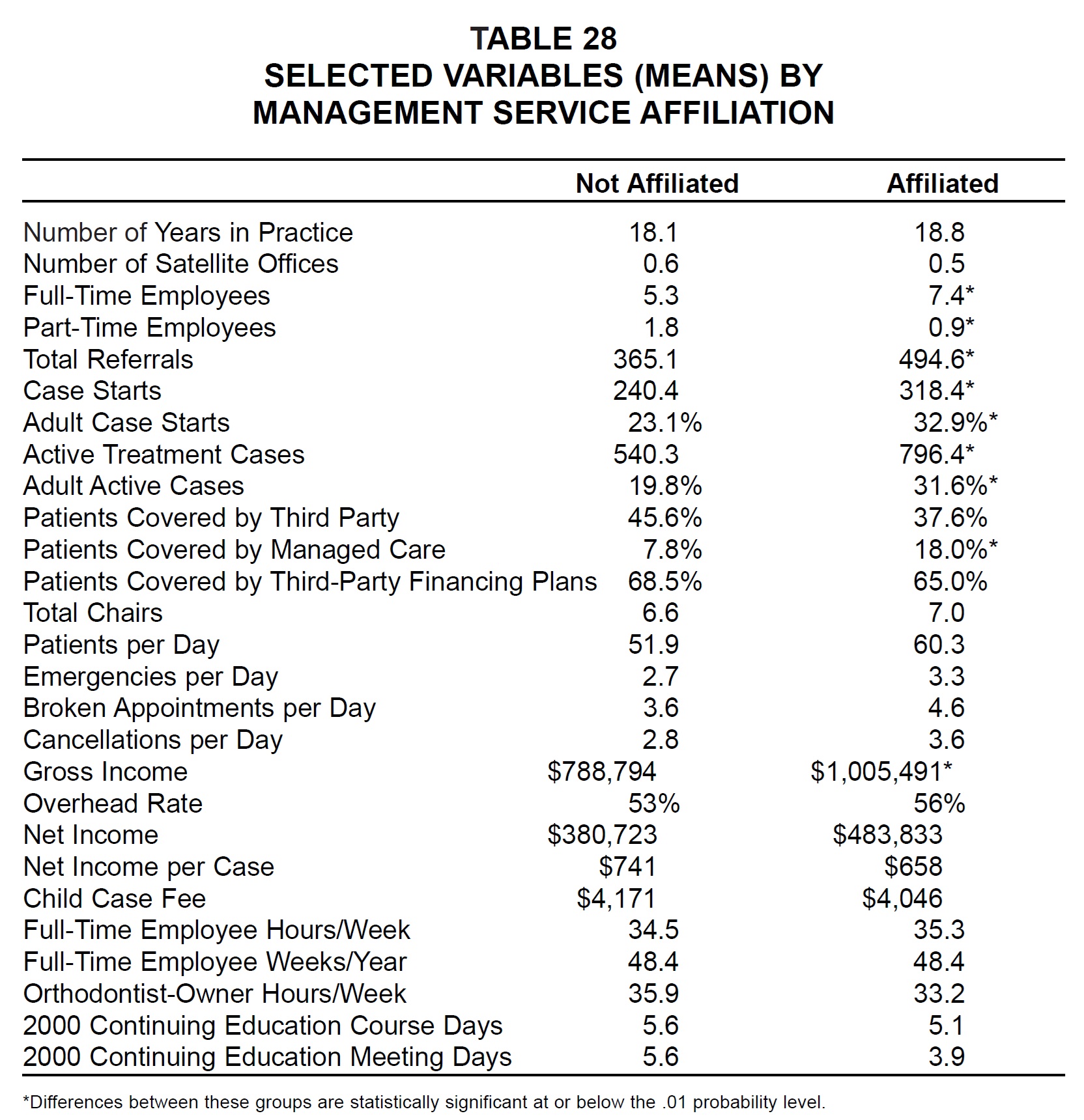

MSO practices reported significantly more employees, cases, adult patients, and managed-care patients than other practices did (Table 28). They also had significantly higher gross income, but when management fees were factored in, they had higher overhead and a less substantial advantage in net income. In fact, their mean child case fees and net income per case were lower than those of traditional practices.

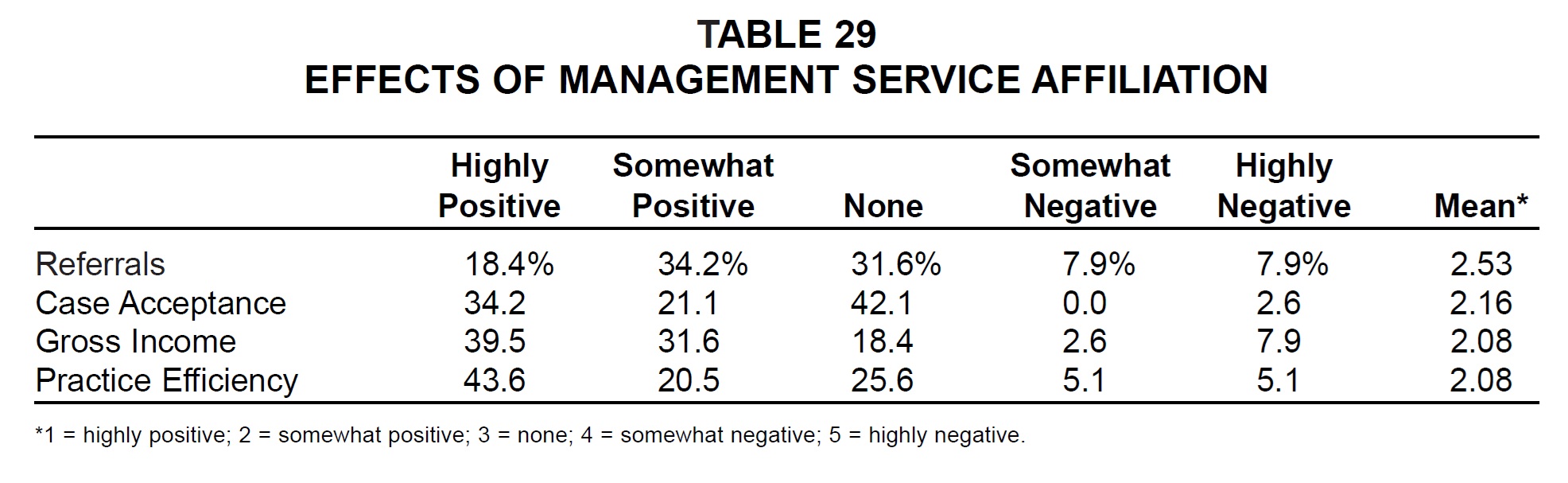

MSO practices were generally positive about the effects of their affiliation, with mean positive ratings slightly higher than those of the 1999 Study (Table 29). When the percentages of respondents calling the effect of affiliation either highly positive or somewhat positive were combined, the highest positive rating was for gross income (71.1%) and the lowest for referrals (52.6%). Conversely, the highest negative rating was for referrals (15.8%) and the lowest for case acceptance (2.6%).

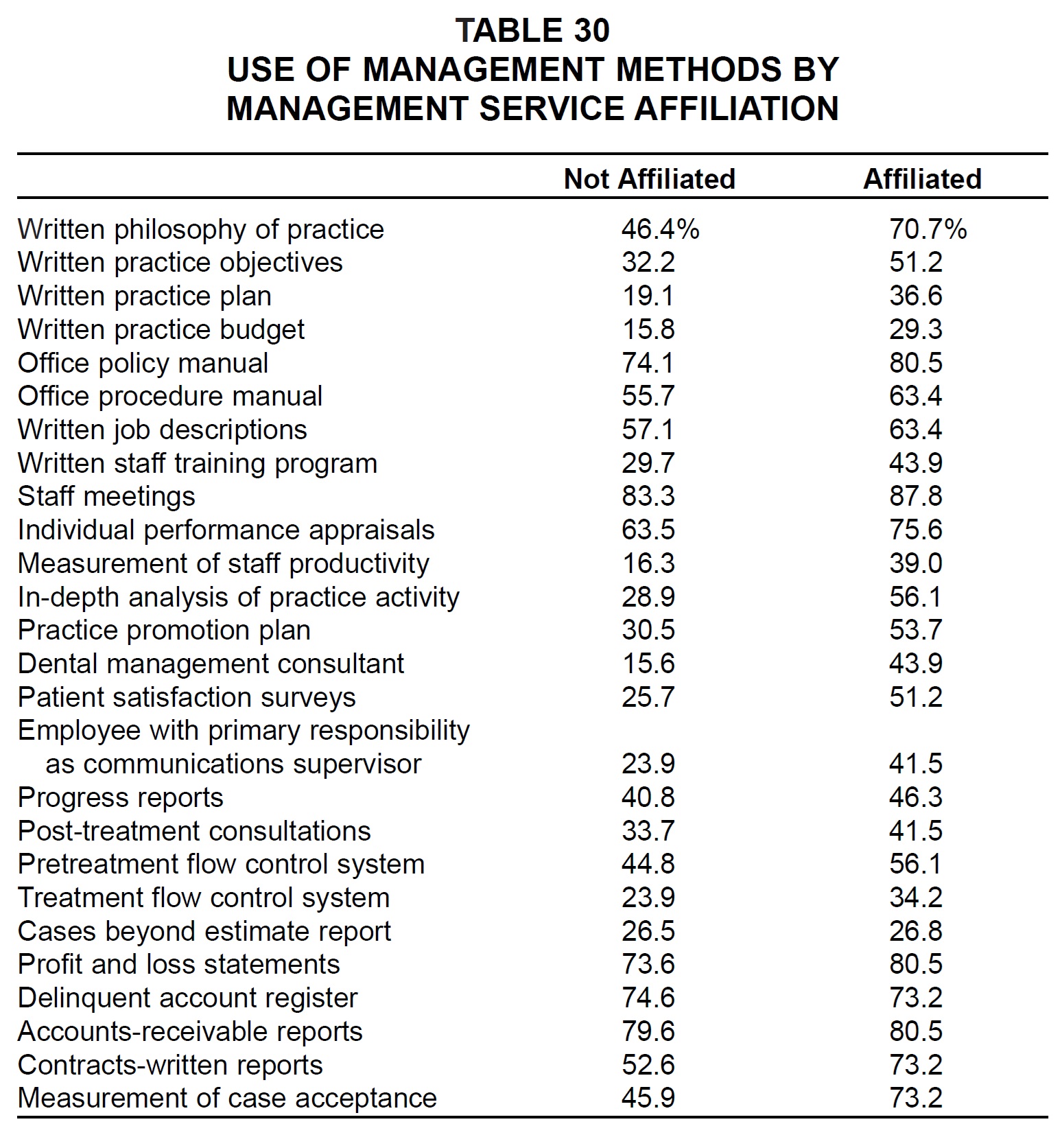

Affiliates of MSOs were much more likely than other practices to use the management methods surveyed, the only exception being delinquent account register (Table 30).

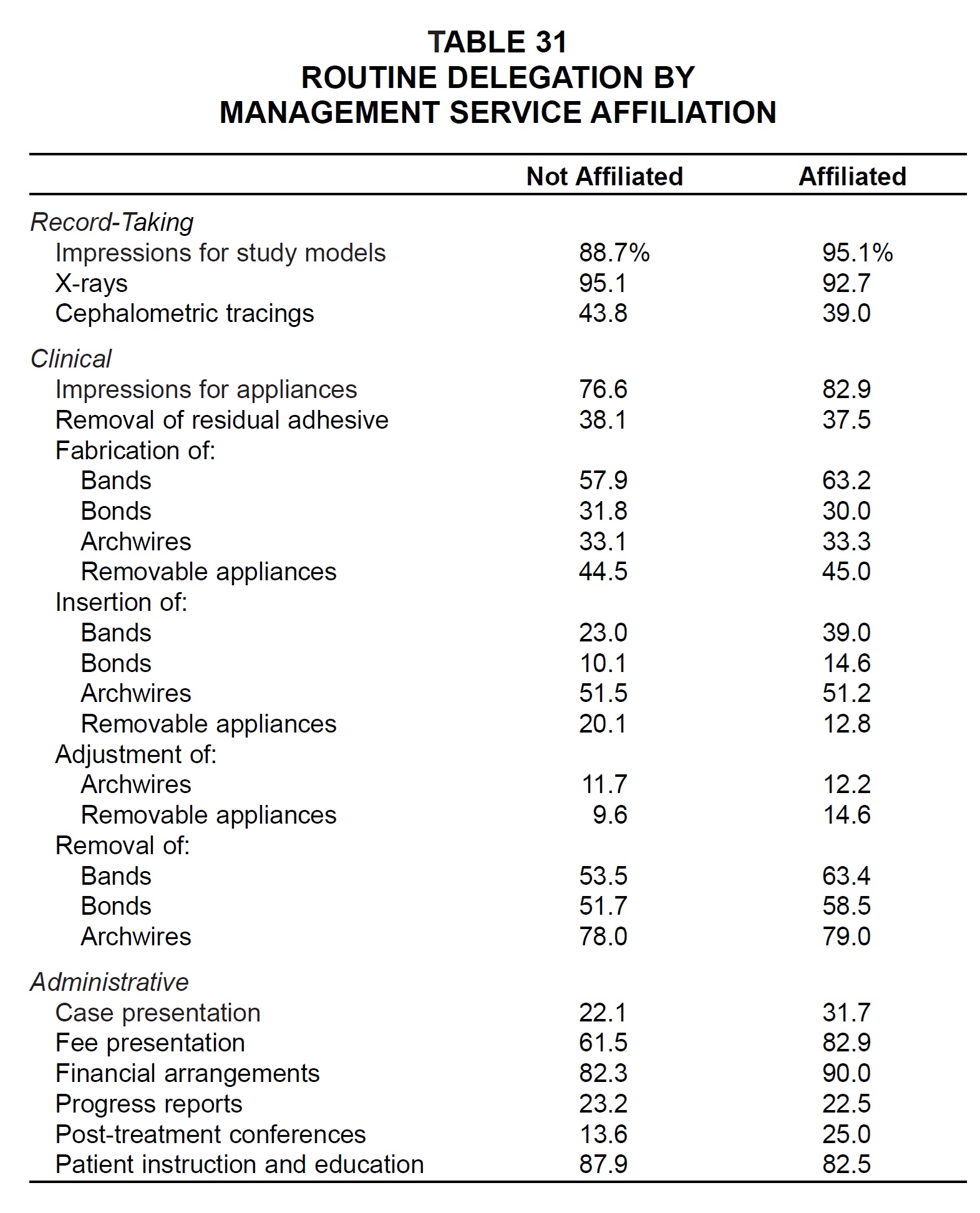

MSO affiliates were also more likely to routinely delegate most of the tasks listed, with the exceptions of x-rays, cephalometric tracings, removal of residual adhesive, fabrication of bonds, insertion of archwires and removable appliances, progress reports, and patient education (Table 31).

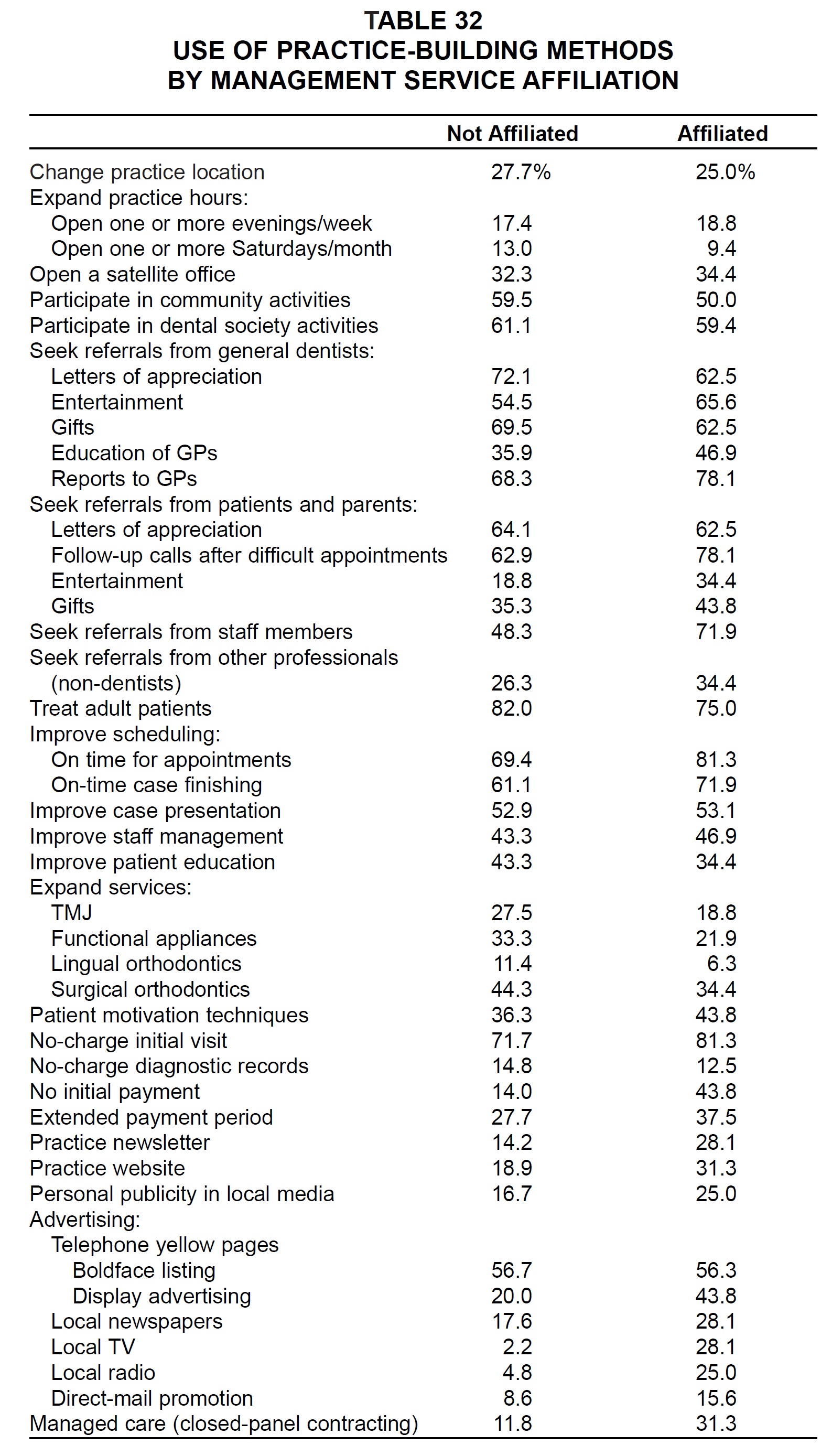

A majority of the practice-building methods in the survey were used more by MSO practices than by others (Table 32). These were: open one or more evenings per week; open a satellite office; entertainment of, education of, and reports to general dentists; follow-up calls after difficult appointments; entertainment of and gifts to patients and parents; seek referrals from staff members and from other professionals; improve scheduling; improve case presentation; improve staff management; patient motivation techniques; no-charge initial visit; no initial payment; extended payment period; practice newsletter and website; personal publicity in local media; all forms of advertising except yellow pages boldface listing; and managed care.

Conclusion

Results of the 2001 JCO Orthodontic Practice Study indicate that the economic prosperity that began around 1990 may finally be slowing, but that orthodontists in general are still better off than they were two years ago. Although case starts did not rise as rapidly since the 1999 Study as they had in the previous four years, there seemed to be plenty of available adolescent patients and even a slight uptick in adult patients. With orthodontists able to raise their fees 4-5% per year and overhead apparently under control, median net income showed a healthy 17% increase over the past two years. In the spring of 2001, at least, when the Practice Study questionnaires were filled out, orthodontists were as optimistic as ever about their future prospects.

As has been true for the entire 20 years of these surveys, the most successful practices appear to be those that make the best use of management and practice-building methods and that delegate as fully as possible to staff members. Improvements in internal and external marketing still offer ample opportunities for growth to those practitioners who seek it.