The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias, or thinking error, that leads individuals with low competence to overestimate their abilities. Identified by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in a 1999 study,1 this phenomenon occurs because inexperienced individuals tend to lack the self-awareness needed to recognize their own shortcomings. As they gain more knowledge about a subject, their initial overconfidence fades, making way for the development of true expertise.

For instance, young orthodontists with many academic accomplishments but little clinical experience might approach complex cases with confidence, but over time, unexpected challenges—such as growth-related changes, root resorption, periodontal complications, or the complexities of patient personalities—will expose the gaps in their understanding. Early in my own career, I was overly confident in my abilities, believing I was more skilled than the orthodontists around me. I quickly dismissed the value of premolar extractions, orthognathic surgery, and conservative treatment plans. Unaware of how much I still had to learn, I held others to a harsher standard than I ever applied to myself.

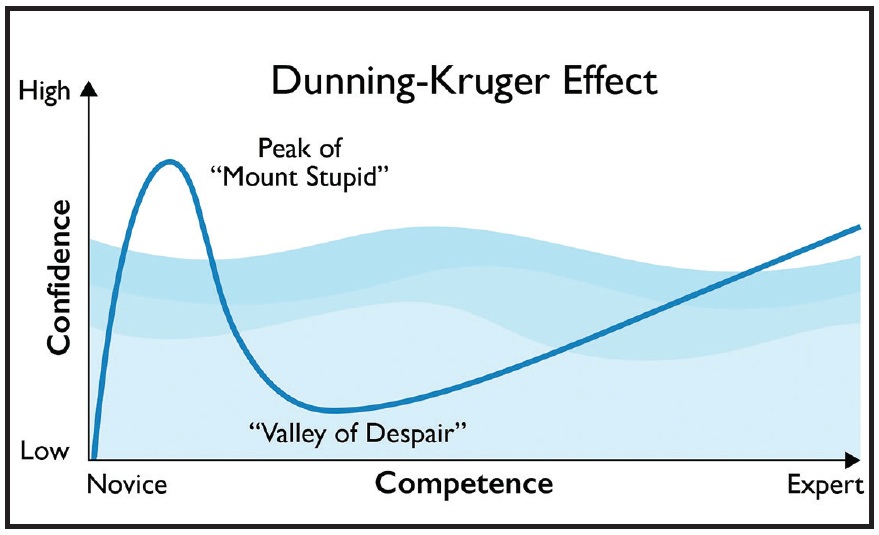

In popular culture, the Dunning-Kruger effect is often illustrated with a graph that demonstrates the initial inverse relationship between confidence and competence (Fig. 1). Confidence (Y-axis) rises sharply at low levels of competence (X-axis), forming a peak informally known as “Mount Stupid,” where individuals grossly overestimate their abilities. As they become aware of their limitations, their confidence plummets into the “Valley of Despair,” only to climb gradually as mastery develops.

Similar articles from the archive:

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER Prisoner 24601 July 2024

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER The Hardest Lesson January 2024

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER Walk Before You Run a Practice May 2022

What I like most about the graph is its resemblance to an iceberg. Much of the learning process is hidden beneath the surface, underestimated by those with limited experience. The iceberg’s tip, visible to neophytes, represents surface-level achievements such as income or case starts. The bulk of the iceberg—comprising the skills, struggles, and insight required to become a great orthodontist—remains unseen until you dive deeper.

If you find yourself slipping into the “Valley of Despair” a few years into practice, my advice is to go easy on yourself. These struggles are a natural part of maturation, especially when your intentions are good. After all, the downward slope of the graph is where the most valuable learning occurs—the bitter lessons of experience that help shape identity. Embracing humility with determination is the quickest way to begin your ascent.

Fig. 1 Conceptual illustration of Dunning-Kruger effect, showing “iceberg of learning.”

Looking back at my career, I realize my trajectory was a classic example of the Dunning-Kruger effect—I thought I knew it all. Only after repeated failures did I learn to approach my work with greater self-awareness and begin to evolve as an orthodontist. It was a challenging period, but it shaped the character I’m proud of today. As you work toward your own professional development, keep this principle in mind: Ego kills growth. Now read that again, right to left.

COMMENTS

.