Bracket Positioning for Smile Arc Protection

Ackerman recently wrote about disruptive orthodontic technology with the view that “orthodontics is the art of the possible” rather than “the science of the improbable”.1 According to him, “Nothing in orthodontics is sacred, and disruptive innovations are always around the corner.” Bracket positioning for Smile Arc Protection (SAP) is an innovation that blends the art of contemporary esthetics with the science behind three-dimensional control of tooth position, making superior esthetic results attainable and more predictable during orthodontic treatment.

In creating extraordinary esthetic enhancement through orthodontic treatment, it is essential that the clinician communicate to the patient what the new “possible” means and how crucial a role a pleasing smile arc plays. To a clinician who has already used SAP positioning with remarkable results, the idea that bracketing for SAP is a “disruptive” innovation will seem odd. This discussion is intended more for those clinicians who want to understand its tenets or may be uncertain about its benefits. The importance of a harmonious curve of the maxillary anterior incisal edges dates back more than half a century, when prosthodontists began to remark how such a curvature could produce a youthful and pleasing esthetic appearance. Although orthodontists have traditionally referred to a “curved smile line”, Sarver prefers the term “smile arc”.2 Building on the work of Ricketts and others, he considers this arc to be of prime importance in planning treatment based on upper incisor position, taking into account both the effects of projected biomechanics and the soft-tissue changes expected with aging. With the steady increase in the prevalence of nonextraction treatment,3 early 3D control of upper anterior tooth positions has become paramount in preventing the incisor flaring and flattening of the smile arc commonly associated with crowding relief.4

Similar articles from the archive:

The focus of this article is to document the philosophy behind and protocols for bracket positioning and other biomechanics that contribute to protecting or enhancing the smile arc in orthodontic patients. These protocols were developed through my many years of clinical case study and experimentation with SAP. The overriding objective is to marry the traditional orthodontic treatment goals of proper function and occlusion with modern standards of beauty.

Concept of Bracket Positioning

Positioning the upper brackets to protect or enhance the smile arc has come to be called SAP bracket positioning. Although bracket positions are individualized to meet each patient’s esthetic needs, the upper incisor brackets are generally placed more gingivally than the canine brackets. The lower posterior brackets are placed somewhat gingivally to avoid occlusion, while the lower anterior brackets are placed somewhat incisally to optimize overbite.

The steps involved in SAP positioning of the anterior brackets have been previously described.5-7 After recontouring the canines and lateral incisors (if required), the incisal edges of the canine bracket wings are positioned gingival to the mesiodistal contact line, as if the self-ligating bracket clip were closed. Next, the distance from the canine bracket slot to the incisal edge of the canine is measured. The central incisor bracket is placed about 1.5mm more gingivally from its incisal edge than the canine bracket is from its recontoured incisal edge. Finally, the lateral incisor bracket is positioned .75-1mm more incisally than the central incisor bracket.

SAP bracket positioning supports today’s esthetic philosophy of compensation for greater width in the upper posterior teeth, with minimal negative space in the buccal corridors (referred to as the “12-tooth smile”). This esthetic concept also calls for optimal axial inclination of the upper anterior teeth, with incisor dominance and a curved smile arc of the upper incisal edges, following the curvature of the lower lip in a posed smile. For many orthodontists, a combination of full enamel display of the upper anterior teeth with 1-1.5mm of gingival display is the most esthetically pleasing and youthful proportion for a posed smile when assessed in natural head position (NHP).8 Such dimensions are also beneficial if a smile is to age well.

Some practitioners have speculated that a more gingival positioning of the maxillary anterior brackets might cause undue tissue swelling. The solution for this problem is to ensure that no composite flash remains around the gingival portion of the pad. Of course, we also rely on good oral hygiene, proper nose breathing, and lack of sensitivity to composite.

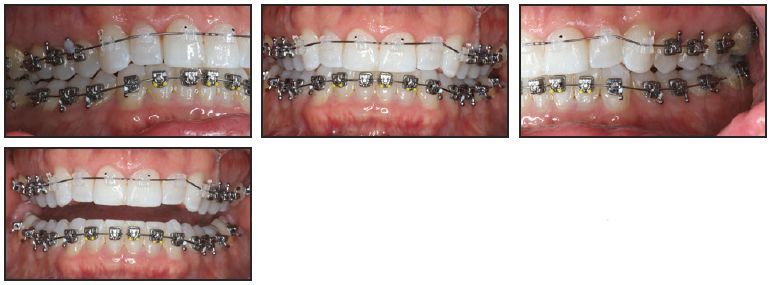

A technique known as the “Active Early” approach comprises progressive case-management strategies that complement SAP bracket positioning for early 3D control. Occlusal guides (bite turbos) and immediate light, short elastics are used from the beginning of treatment to match the lower occlusal plane with the upper. In a patient with deep overbite, this technique helps erupt the lower molars and extrude the upper anterior teeth as it moves them slightly clockwise. Case 1 demonstrates how the smile arc, enamel and gingival displays, and occlusal plane can be positively affected by SAP bracket positioning and the “Active Early” approach (Figs. 1-6).

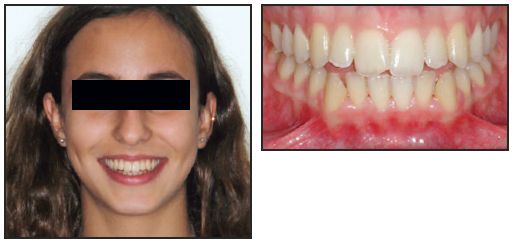

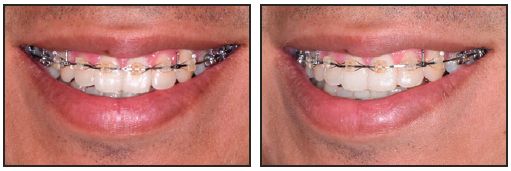

Fig. 1 Case 1. 17-year-old female patient with disappointing result from previous 3.5 years of orthodontic treatment. (Case courtesy of Dr. Nimet Guiga, Cascais, Portugal.)

Fig. 2 Case 1. Brackets bonded with Smile Arc Protection (SAP) bracket positioning. Progressive case management strategies included inverted upper anterior brackets; posterior occlusal guides (bite turbos); and immediate light, short Class III elastics.

Protecting and Enhancing Smile Arcs

Factors that can make it more difficult to protect existing smile arcs or enhance inadequate smile arcs during treatment include5:

- Inappropriate conventional bracket positioning, which typically reduces or flattens the smile arc (and wire plane) during leveling.

- The relative steepness or flatness of the occlusal plane (the flatter the plane, the more difficult it is to manage the smile arc esthetically).

- Incisor proclination, whether preexisting or iatrogenic.

- A particularly broad anterior archform, in which the excessive intercanine span tends to flatten the smile arc.

- Steep upper canine tips and inappropriate canine bracket positioning in relation to the incisors.

- Irregular shapes or size disproportions among the incisors and canines.

SAP bracket placement can positively affect each of these factors, as detailed below.

Fig. 3 Case 1. Smile arc developing after eight months of treatment.

Fig. 4 Case 1. Patient after 15 months of treatment, with smile exhibiting all desirable esthetic characteristics.

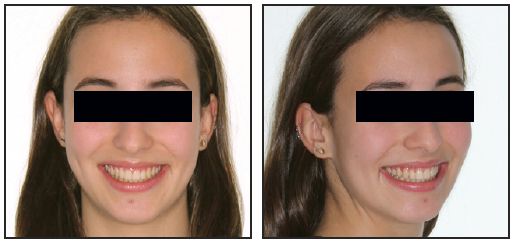

Fig. 5 Case 1. Comparison of pretreatment (A) and post treatment (B) photos, demonstrating improvements in smile arc, cant of upper occlusal plane, incisor and gingival display, and archform, with proper “white and pink” esthetic proportions.

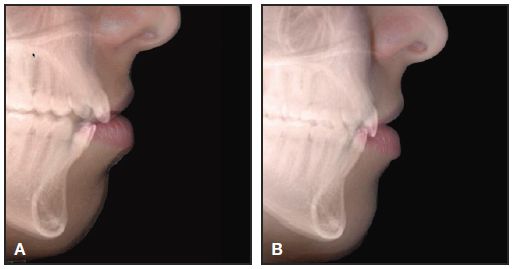

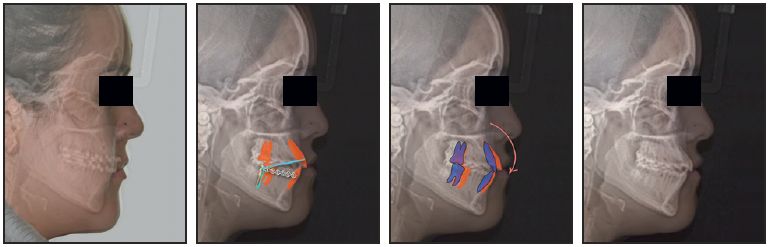

Fig. 6 Case 1. Comparison of pre-treatment (A) and post-treatment (B) lateral cephalograms, showing slight clockwise rotation of maxillary occlusal plane with upper incisor extrusion in relation to stomion.

Effect of Bracket Position on Wire Plane

If a full enamel display with 1-1.5mm of gingival display provides the most esthetically pleasing and youthful smile dimensions, it is important to appreciate the negative effect of leveling—especially upper incisor intrusion in a deep-bite case—on the smile arc. Upper incisor intrusion is only rarely esthetically desirable, even for a Class II, division 2 malocclusion. If the patient has a gummy smile, an esthetic smile arc should be developed by using SAP bracket positioning and temporary anchorage devices or utility aches for intrusion, rather than relying on bracket position.

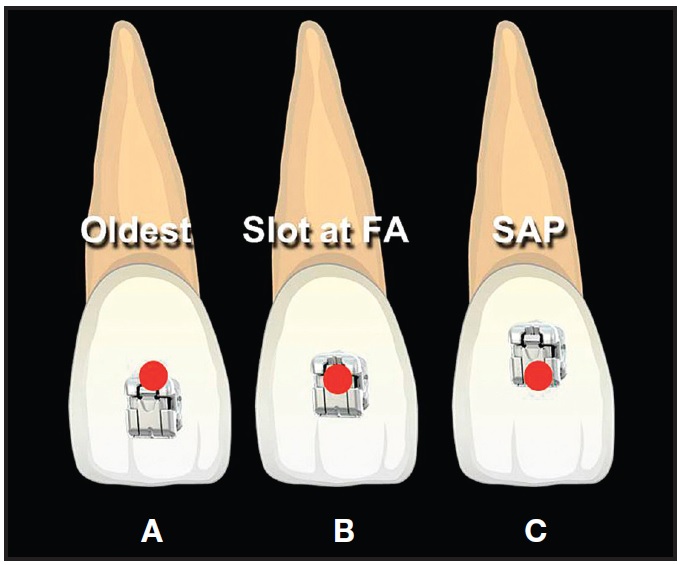

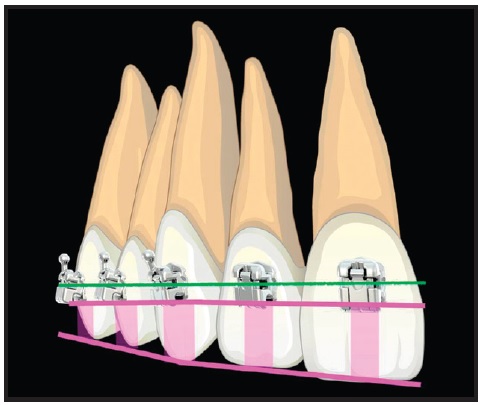

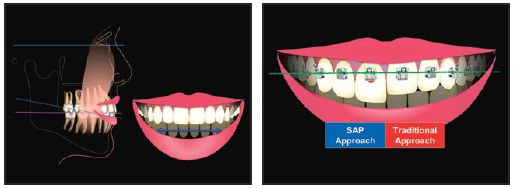

To develop a pleasing smile arc and positively affect the anterior portion of the upper occlusal plane cant, the maxillary anterior brackets are positioned more gingivally for SAP than in traditional techniques (Fig. 7). The maxillary archwire plane is then parallel to the upper lip; the incisal edges of the upper anterior teeth will follow the lower lip with treatment (Fig. 8). The divergence of the wire from the occlusal cusp tips or incisal edges increases from posterior to anterior (Fig. 9). The greater the differential from the buccal segments to the anterior segment, the more the wire plane helps increase the maxillary occlusal plane cant in relation to true Frankfort horizontal (NHP). When needed, miniscrews can be utilized as anchorage to intrude the lower anterior teeth, allowing more vertical movement of the upper incisors.

Fig. 7 Bracket placement concepts. A. Traditional. B. Slot at facial axis point. C. SAP positioning. (© Dr. Rungsi Thavarungkul, Bangkok, Thailand.)

Fig. 8 With SAP bracket positioning, maxillary archwire plane is parallel to upper lip; incisal edges of upper anterior teeth will follow lower lip during treatment. (Case image courtesy of Dr. Tomás Castellanos, Bogotá, Colombia.)

Fig. 9 To develop pleasing smile arc display and positively affect upper occlusal plane cant, maxillary anterior brackets must be positioned more gingivally for SAP than in traditional techniques. Divergence of wire from cusp tips or incisal edges increases from posterior to anterior. (© Dr. Rungsi Thavarungkul, Bangkok, Thailand.)

Favorable wire planes produced by SAP bracket positions induce extrusion of the upper incisors relative to the upper premolars, resulting in the application of a clockwise moment to the upper anterior teeth from the outset of treatment. When the occlusion is disarticulated with bite turbos and mechanics are supported by very light, short elastics from the first appointment, uprighting of proclined teeth will begin, even on light, round wires. Clinicians report that these techniques can improve upper incisor and gingival display, smile arc, and incisor inclinations as early as the third appointment. Taking “every patient, every appointment” clinical photos is exceptionally helpful in assessing esthetic progress, so that case management can be adjusted accordingly.

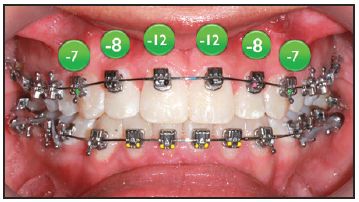

When additional retroclination of the incisors is desired, the mechanics can be further supported by inverting the upper anterior brackets 180°, producing active lingual crown torque in the slot with dimensional archwires9 (Fig. 10). Inversion does not alter the tip or in-out geometry of well-designed incisor brackets. Unfortunately, due to a number of common factors—oversize bracket slots, inconsistent slot geometries (as caused by poor manufacturing tolerance control10), overly large slot corner radii, variable self-ligating bracket rigidity, and use of excessively small wires— even the highest-quality appliances are not able to deliver consistent expression of their stated torque prescriptions, because torsional play overrides the differences between various prescription values. Moreover, most clinicians do not fill the slot, which further degrades torsional expression.

The H4* bracket, which features a one-piece self-ligating design, a rigid door, tight manufacturing tolerances, and reduced slot depth (.026" vs. the typical .028"), overcomes some of these challenges and improves efficiency by reducing torsional play. Its use in a well-developed clinical methodology can allow a more purely “straightwire” approach, even when the bracket slot is not filled. The combination of the H4 bracket and progressive “Active Early” case-management strategies goes a long way toward overcoming many of the control problems typically encountered with other passive self-ligating appliance systems.

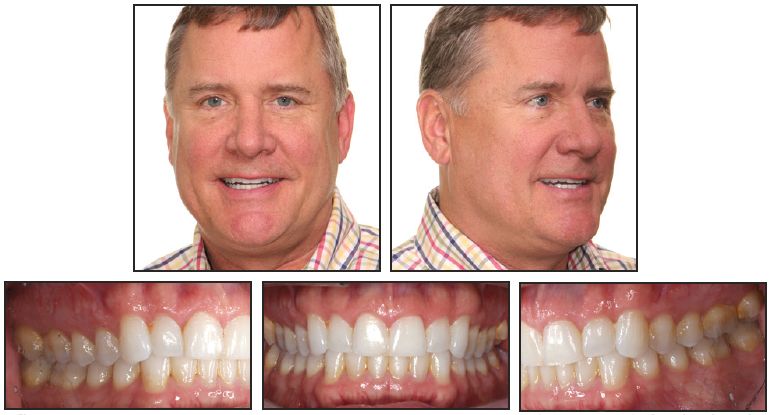

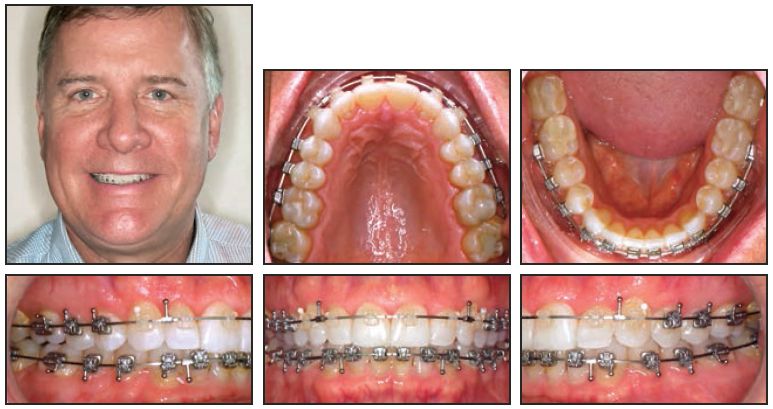

Case 2, in progress at seven months, demonstrates the effect of SAP bracket positioning on the wire plane and the resulting smile arc (Figs. 11-13).

Fig. 10 When additional retroclination of anterior teeth is desired, inverting upper anterior brackets 180° provides additional bracket torque, as indicated by circled numbers. (Case image courtesy of Dr. Tomás Castellanos, Bogotá, Colombia.)

Fig. 11 Case 2. 52-year-old male patient with reverse smile arc and “hanging” canines before treatment.

Fig. 12 Case 2. Initial bonding with SAP bracket positioning.

Fig. 13 Case 2. After seven months of treatment. Lower arch will continue to level.

Effect of Bracket Position on Occlusal Plane

Research has shown that actual clinical torsional play in self-ligating brackets can be as much as two and a half times more than predicted by mathematical models,11 making reliable expression of 3rd-order movements problematic. With SAP bracket positioning, the effective prescription of the bracket is reduced relative to the occlusal plane, so that torsional moments for uprighting proclined teeth are engaged early in wire progressions.

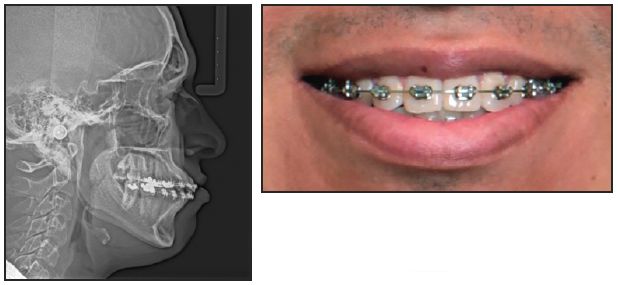

It is important to recognize that the maxillary occlusal plane, as viewed in NHP, is a significant contributor to the esthetics of the smile (Fig. 14). Obviously, the flatter the plane, the more difficult it is to manage the case esthetically (Fig. 15). Rotating the maxillary occlusal plane clockwise will produce more incisor display and a more convex smile arc. Counterclockwise rotation, which can occur when the upper anterior brackets are placed incisally to the recommended SAP positions, can result in esthetic decline.

In combination with the appropriate use of bite turbos and immediate light, short elastics, SAP bracket positioning helps control the cant of the maxillary occlusal plane from the outset of treatment, offering a wider range of treatment options. Individual bracket positions should be based mainly on the length of the canines and incisors, as well as the patient’s esthetic needs. If the occlusal plane is flat, the gingival bracket divergence should be increased even farther from traditional positioning to enhance enamel and gingival incisor display. In a deep-bite case, the SAP bracket divergence in the upper arch is counteracted by increased overleveling of the lower arch to achieve an optimal overbite. Because it is crucial not to deepen the bite while enhancing the smile arc with individual bracket positioning,4 anterior bite turbos should be used to allow eruption of the lower molars.

Fig. 14 Flat smile line detrimentally affects esthetics of post- treatment smile.

Fig. 15 With traditional bracket placement, treatment of brachyfacial patient with flat occlusal plane can result in flat smile line. (© Dr. Rungsi Thavarungkul, Bangkok, Thailand.)

Fig. 16 Case 3. 31-year-old female patient with proclined upper incisors and flat smile line before treatment.

Effect of Bracket Position on Proclination

One of the challenges presented by crowded nonextraction cases is to control or correct preexisting upper incisor proclination, or to prevent the proclination that often results from space-gaining mechanics. Incisor proclination adversely impacts esthetics in many ways. In the frontal smile, labially inclined incisors are visually shorter and make an esthetic smile arc more difficult to obtain by reducing incisor dominance and the effective crown height and enamel display, as demonstrated in Case 3 (Figs. 16-18). In the lateral smile, because the eye is capable of detecting roughly 5° or more of proclination, the viewer will be more sensitive to changes in axial inclination than to the anteroposterior position of the incisors.8

While esthetic incisor position has traditionally been assessed through cephalometric measurements, it can also be evaluated by means of photographs taken in NHP with frontal, 45°, and posed profile smiles. Again, “every patient, every appointment” clinical photos are important in tracking esthetic progress and adjusting case management accordingly.

Since the most effective application of force is close to the center of resistance, bracket positioning also has an important effect on torque.12 Gingival maxillary anterior bracket placement has been criticized because it lowers the effective torque in the slot. If the incisal portion of the pad is fully seated against the enamel, however, the change in effective torque will be minimal. With proclined incisors, this slightly lower effective torque actually improves appliance performance by offsetting the wire play associated with undersize finishing archwires. It is also useful in a situation where torque within the slot is desirable. SAP bracket positioning moves the wire plane closer to the center of resistance of the tooth, providing more control. In crowded nonextraction cases or patients with preexisting upper incisor proclination, SAP bracket positioning has a positive effect because it lowers the effective torque prescription. Upper anterior flaring can be controlled even more by inverting the brackets 180° and using .017" × .025" wires in the .022" × .026" slots of the H4 brackets.

Fig. 17 Case 3. Brackets bonded with SAP bracket positioning (anterior brackets inverted); .020" × .020" H4 Beta Titanium* archwire engaged after eight months of treatment.

Fig. 18 Case 3. Patient after 16 months of treatment.

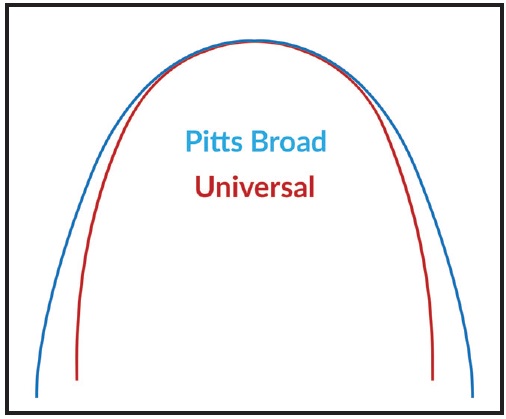

Effect of Broad Anterior Archform on the Smile Arc

Archforms that are excessively broad in the anterior region tend to flatten the smile arc as a geometric consequence of the extended intercanine span. This flattening effect is compounded by incisal bracket placement on the upper anterior teeth. Because the ligation method has no effect on archform, SAP bracket positioning must be combined with an improved archform to address this concern. The H4 Pitts Broad* archform (Fig. 19) is broad at the molars, filling out the buccal corridors; tapered in the anterior segment, improving incisor flow and presentation; and moderate in width at the canines, fostering a 12-tooth smile during animation, as shown in Case 4 (Figs. 20,21).

Fig. 20 Case 4. 25-year-old male patient who transferred in, after 5.5 years of treatment, with reverse smile arc and proclined incisors resulting from use of excessively broad anterior archforms.

Fig. 21 Case 4. After nine months of treatment with SAP bracket positioning and H4 Pitts Broad archform.

Effect of Steep Canine Tips on the Smile Arc

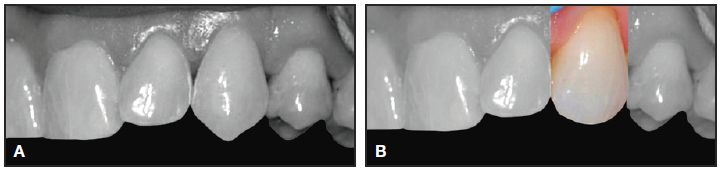

Esthetically shaped canines at the proper inclination are essential to a beautiful smile. Inappropriately shaped canines can create two esthetic problems. First, a steep, pointed canine tip results in a “hanging” canine when the contact point between the canine and lateral incisor is aligned (Fig. 22A). On the other hand, if the canine tip is aligned with the lateral incisor but the contact point is too gingival, the embrasure will be unsightly (Fig. 22B). Performing a positive or negative coronoplasty before bonding will optimize the esthetic contours of the canine while still allowing canine disclusion (Fig. 23), as shown in Case 5 (Fig. 24).

Fig. 22 A. If bracket is placed too incisally on steep, pointed canine, contact will be too gingival. B. If canine tip is aligned with lateral incisor, but contact point is too gingival, embrasure will be unsightly.

Fig. 23 A. Typical “hanging” canine. B. Idealizing canine contours prior to bonding promotes correct bracket positioning.

Fig. 24 Case 5. A. 11-year-old female patient with steep, pointed canines before treatment. B. Canine disclusion achieved after contouring prior to bracketing.

Effect of Irregular Tooth Shapes and Proportions on Bracket Position

Irregular tooth shapes or size disproportions among the incisors and canines are best addressed through positive or negative coronoplasty prior to bracketing or, at least, early in treatment. Improving the height-width ratio of the “white and pink” tissues is a critical esthetic requirement. Of the three means of crown lengthening, two can be performed by orthodontists: adding composite resin to the incisal edges, or soft-tissue revision with a diode laser. Today’s composite resin is easy to apply and durable over the long term. (The third method of crown lengthening is to lift a periodontal flap and recontour bone around the labial aspect of the tooth, which is generally performed by a periodontist.)

The esthetic principle of incisor dominance dictates that the upper central incisor must be the predominant tooth in the esthetic smile.11 This means it must display the widest “actual” and “visual” crown and the widest flat surface for light reflection.13 It must also be the longest tooth by both actual length and proximity to the idealized lower lip curvature in the posed smile. SAP bracket positioning facilitates incisor dominance because the divergence in bracket progression places the central incisor bracket at the most gingival position of the upper anterior teeth.

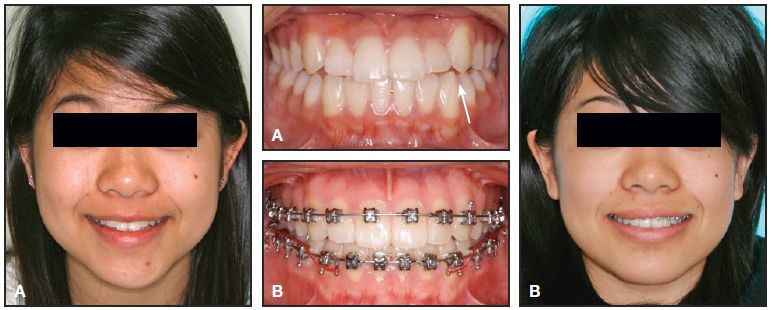

Case 6 exemplifies the standards of today’s smile esthetics, including proper dental and gingival display and a 12-tooth smile with a pleasing smile arc. Treatment with SAP bracket positioning and progressive case-management strategies also resulted in an improved occlusal plane in this patient (Figs. 25-29).

Fig. 25 Case 6. 21-year-old female patient with hypertrophic masseter muscles, Class III tendency, proclined upper incisors, and reverse curve smile arc before treatment. (Case images courtesy of Dr. Tomás Castellanos, Bogotá, Colombia.)

Fig. 26 Case 6. Treatment plan involved extracting third molars; injecting botulinum toxin in masseters one month prior to treatment; performing gingival recontouring and positive coronoplasty with composite resin; placing temporary anchorage devices in upper posterior buccal shelf; and engaging light, short Class III elastics at first appointment to distalize lower arch.

Fig. 27 Case 6. After nine months of treatment, showing maxillary anterior brackets bonded with SAP bracket positioning and inverted for additional crown torque (circled numbers).

Fig. 28 Case 6. A. After 12 months of treatment. B. After 15 months of treatment and gingival recontouring.

Fig. 29 Case 6. Comparison of photographs taken before treatment (A), after debonding (B), and after gingival recontouring (C), showing effectiveness of SAP bracket positioning and progressive case management strategies.

Conclusion

The two keys to the acceptance of any disruptive technology are adequate education and the means to adopt the disruptive idea. In terms of the SAP bracketing concept and its recommended case-management strategies, education of all the stakeholders—including patients, referring dentists, parents, hygienists, and the orthodontist’s own staff—must convey a keen understanding of “what is possible”. For stakeholders to embrace the SAP philosophy, they must first appreciate what a truly beautiful smile entails. The use of highquality comparative photographs is invaluable in creating this understanding.

The SAP technique can easily be incorporated into a practice by using a combination of well-designed orthodontic appliances manufactured to exacting standards and effective clinical protocols, as described in this article. Clinicians thus have the means to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of treatment while providing consistently excellent case results. Treatment planning for esthetic smile design will become more and more predictable as it helps orthodontists open up “the art of the possible”.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: I would like to acknowledge Dr. Rungsi Thavarungkul (Bangkok, Thailand) for his excellent illustrations of the dentition in support of the concepts explained in this discussion. I give particular thanks to Dr. Duncan Brown (Calgary, Alberta) for his editing assistance and to Drs. Nimet Guiga (Cascais, Portugal) and Tomás Castellanos (Bogotá, Colombia) for their excellence in orthodontics and for contributing cases shown in this article. I would also like recognize three groups of orthodontists for their contributions to my efforts in achieving the highest level of esthetics while ensuring proper occlusion and function. The first includes the dedicated teams at OrthoEvolve, OC Orthodontics, and the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry orthodontic clinic, where I teach. These teams have been instrumental in the development of the “Active Early” case-management strategies recommended here. The second group is the University of the Pacific residents who have worked diligently to employ these protocols. The third group comprises orthodontists around the world who have helped experiment with the concepts of SAP bracket positioning and the other recommended strategies.

FOOTNOTES

- *Trademark of Ortho Classic, Inc., McMinnville, OR; www.ortho classic.com

- **Trademark of Ortho Technology, Lutz, FL; www.ortho technology.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ackerman, M.B.: The next disruptive innovation in orthodontics, Ben There Done That, June 2016, orthopundit.com, accessed Nov. 15, 2016.

- 2. Sarver, D.M.: The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: The smile arc, Am. J. Orthod. 129:96-111, 2001.

- 3. Janson, G.; Maria, F.R.T.; and Bombonatti, R.: Frequency evaluation of different extraction protocols during 35 years, Prog. Orthod. 15:51, 2014.

- 4. Ackerman, J.L.; Ackerman, M.B.; Brensinger, C.M.; and Landis, J.R.: A morphometric analysis of the posed smile, Clin. Orthod. Res. 1:2-11, 1998.

- 5. Pitts, T.: Begin with the end in mind and finish with beauty, Eur. J. Clin. Orthod. 2:39-46, 2014.

- 6. Pitts, T.: Secrets of excellent finishing, News Trends Orthod. 14:6-23, 2009.

- 7. Pitts, T.: Begin with the end in mind: Bracket placement and early elastics protocols for smile arc protection, Clin. Impress. 17:4-13, 2009.

- 8. Cao, L.; Zhang, K.; Bai, D.; Jing, Y.; Tian, Y.; and Guo, Y.: Effect of maxillary incisor labiolingual inclination and anteroposterior position on smiling profile esthetics, Angle Orthod. 81:121-129, 2011.

- 9. Pitts, T. and Brown, D.: Overcoming challenges in PSL with “active early” and H4, Protocol 7:8-18, 2016.

- 10. Dalstra, M.; Eriksen, H.; Bergamini, C.; and Melsen, B.: Actual versus theoretical torsional play in conventional and self-ligating bracket systems, J. Orthod. 42:103-113, 2015.

- 11. Bhuvaneswaran, M.: Principles of smile design, J. Conserv. Dent. 13:225-232, 2010.

- 12. Sardarian, A.; Danaei, S.M.; Shahidi, S.; Boushehri, S.G.; and Geramy, A.: The effect of vertical bracket positioning on torque and the resultant stress in the periodontal ligament—A finite element study, Prog. Orthod. 15:50, 2014.

- 13. Brandao, R.C.B. and Brandao, L.B.C.: Finishing procedures in orthodontics: Dental dimensions and proportions (microesthetics), Dent. Press J. Orthod. 18:147-174, 2013.