MANAGEMENT AND MARKETING

Influence of Student-Loan Debt on Orthodontic Residents and Recent Graduates

This column is compiled by JCO Contributing Editor Robert S. Haeger, DDS, MS. Every few months, Dr. Haeger presents a successful approach or strategy for a particular aspect of practice management. Your suggestions for future topics or authors are welcome.

The cost of college and the ability to repay student loans are major topics of debate in our universities today. For example, should a private college stop offering degrees in teaching when the tuition reaches $60,000 per year? Similarly, how do orthodontic students grapple with their debt loads as tuition continues to escalate faster than anticipated income? This month's column addresses the issues of student loans and mounting debts, as well as their impact on the lifestyle and expectations of current residents and recent graduates.

I would advise every orthodontic program applicant and resident to analyze the implications of this article. The statistics presented here can shape your outlook on future employment and help you plan where to live - or at least make you consider buying a less expensive car. These numbers may also make you think twice about the programs where you apply. Knowledge is king: knowing more about debt load, income opportunities, and lifestyle options will serve to align your expectations with reality, which will ultimately make you happier.

RSH

Similar articles from the archive:

Influence of Student-Loan Debt on Orthodontic Residents and Recent Graduates

According to the ADA's 2015 Supply of Dentists Survey, there are around 10,000 orthodontic specialists in the United States, making orthodontics the largest of the nine recognized specialties.1 The 65 accredited orthodontic programs in the United States graduate approximately 380 students each year.2

The average student-loan debt for 2013 dental-school graduates was more than $215,0003; the average debt of orthodontic residents in a May 2007 survey was $165,226.4 According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the mean annual wage for an orthodontist in 2013 was $196,270,5 up from $176,900 in 2006 (an 11% increase over seven years). Residents responding to the May 2007 survey expected to earn an average $137,570 after graduation, increasing to an average $306,336 five years after graduation (a 123% increase over five years). The reality is that while student-loan debt is steadily increasing, salaries are not keeping pace. Orthodontic graduates' expectations of their earning potential may not be rational in the current economy.

We have seen no studies comparing student-loan indebtedness to average salaries and available associate positions since the 2008 economic recession. During that period, orthodontic graduates' ability to find ideal job situations appears to have declined substantially. Fewer established practices have been available to purchase, and most owner-orthodontists do not need full-time associates. Multispecialty corporate offices and general dentists offering "in-house" orthodontics have increased the competition for graduates. To make things worse, tuition rates for orthodontic programs have risen over the past few years, so that many students are graduating with significantly higher debt loads.

This study assesses the financial hardships facing recent orthodontic graduates and current residents, with the aim of identifying methods to manage these obstacles more effectively.

Methodology

Two surveys were designed for distribution to current orthodontic residents and recent graduates (less than seven years from graduation). Residents were asked 38 questions and graduates 50 questions about their demographics, education, debt, and career choices. The study was approved by the institutional review board of A.T. Still University and administered in coordination with the Pacific Coast Society of Orthodontists (PCSO).

Questionnaires were e-mailed in March 2015 to the PCSO's membership list of 427 graduates and 265 residents. Over the next two months, two reminder e-mails were sent to those who had not responded. No compensation or other incentives were offered for completing the survey, which was submitted anonymously using SurveyMonkey.com. A total of 102 graduates (24% response rate) and 72 residents (27%) replied, for an overall response rate of 25%.

Results

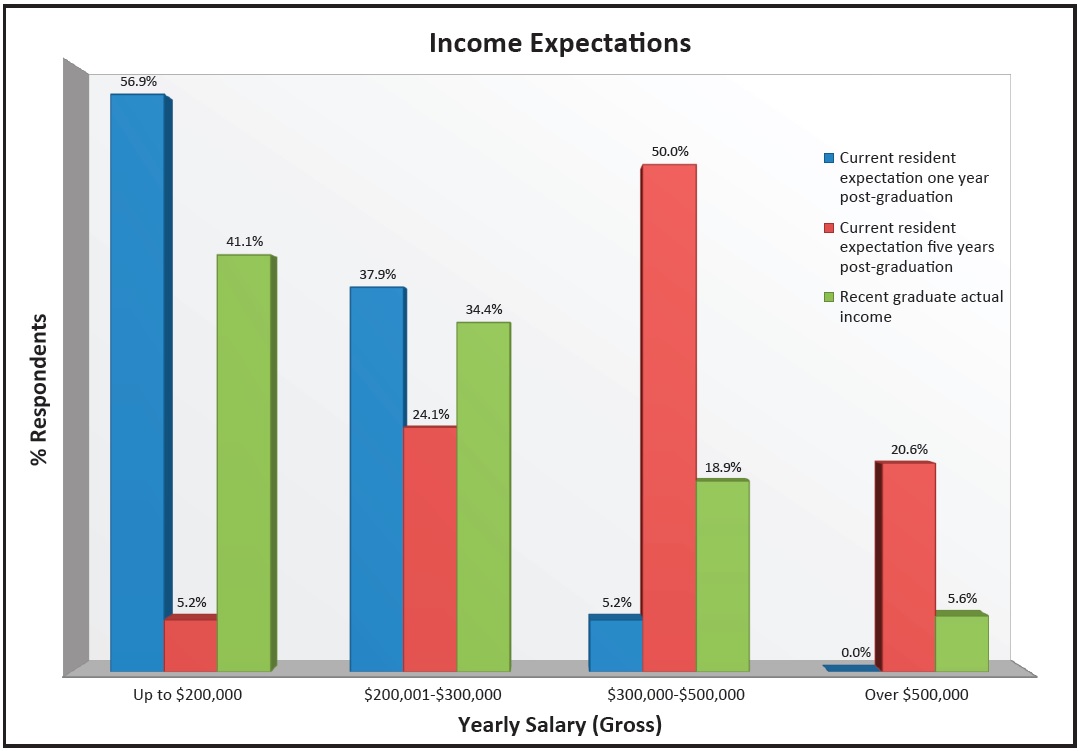

Of the 174 respondents, 63% were male and 37% were female, with an average age of 30-34 (Table 1). Residents came from orthodontic programs in 28 of the 50 states, the most common being California (not surprising since only PCSO members were surveyed). About 56% of the recent graduates had practiced orthodontics for three to seven years; 61% were practicing in urban areas (population greater than 50,000), while 37% were practicing in suburban areas (2,500-50,000). Eighty-two percent reported working full-time, defined as 30 hours or more per week.

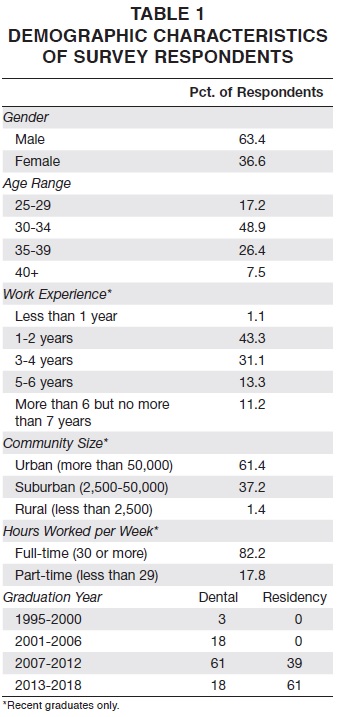

Sixty-four percent of all respondents reported no debt from their undergraduate education. On the other hand, about half of the total respondents had dental-school debt of more than $200,000, and 32% had residency debt greater than $200,000. Moreover, 78% of the respondents indicated that they received no stipends from their residency programs.

Fifty-five percent of the recent graduates reported residency tuition costs between $50,000 and $200,000; 53% listed the same range for dental-school tuition (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Dental-school and residency loan debt for current residents and recent graduates.

In contrast, 44% of the current residents reported tuition costs of more than $200,000 in their programs, while 71% said they had paid more than $200,000 for dental school. A majority of the graduates had completed dental school between 2007 and 2012. Comparing 2010 data from the American Dental Education Association (ADEA) to figures from 2014, tuition increased by an average 14.6% per year during that period.3 As a result, students are entering their residency programs with substantially more dental-school debt than in previous years. It should be noted that the ADEA data include undergraduate debt, which was found to be negligible - 86% of the ADEA respondents reported undergraduate debt of $25,000 or less.3 Almost half of all respondents to our study indicated that tuition costs had influenced their choices of residency programs.

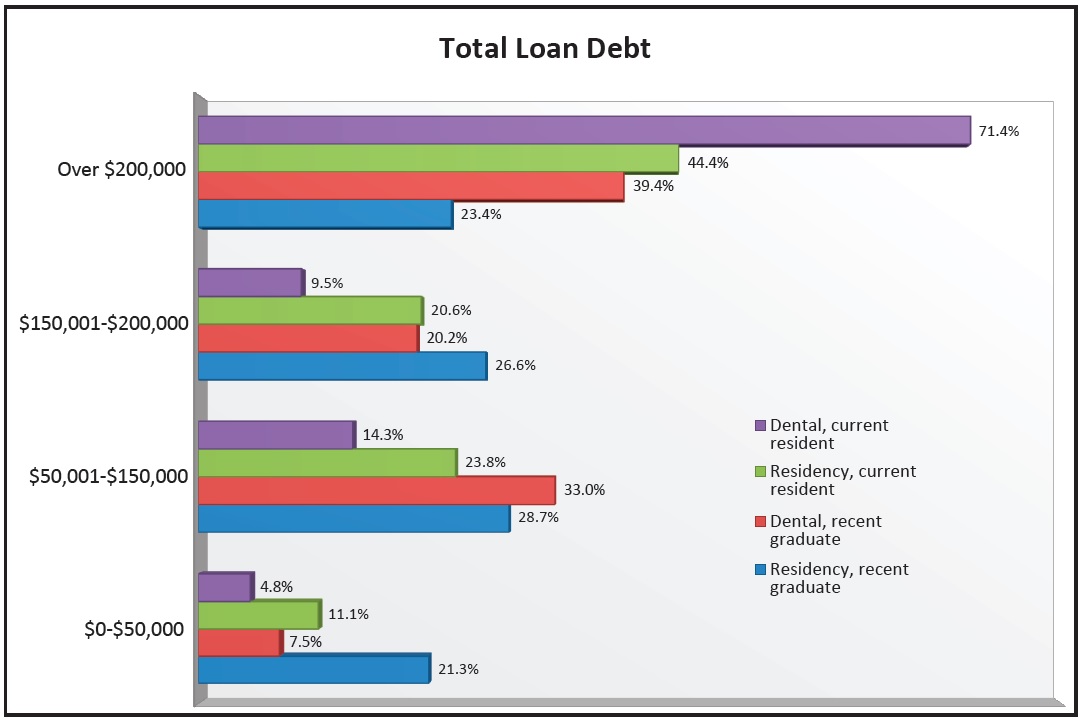

Eighty-seven percent of the graduates had started working within three months of graduation, but 80% said it was difficult to find ideal positions. In addition, half of the graduates reported difficulty finding work in their preferred states. These results are corroborated by the 2013 Benson & Clark annual resident survey, which showed that at least 68% of the responding graduates since 2010 had found it difficult to obtain positions.6 Among the current residents in our survey, 70% anticipated having difficulty finding work after graduation, with 52% hoping to locate private-practice positions, either as an owner or an associate, and 28% considering corporate practice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Practice mode of recent graduates immediately after graduation and currently; anticipated employment of current residents following graduation.

Almost all planned to work full-time.

The most common practice modality immediately after graduation was orthodontist-owned private practice (52%), followed by corporate dental practice (32%). This trend continued for several years after graduation; at the time of the survey, 64% of the graduates were in private practice as either owners or associates, while 24% were in corporate settings. The proportion of those who owned their practices increased from 27% to 51% as years in practice increased.

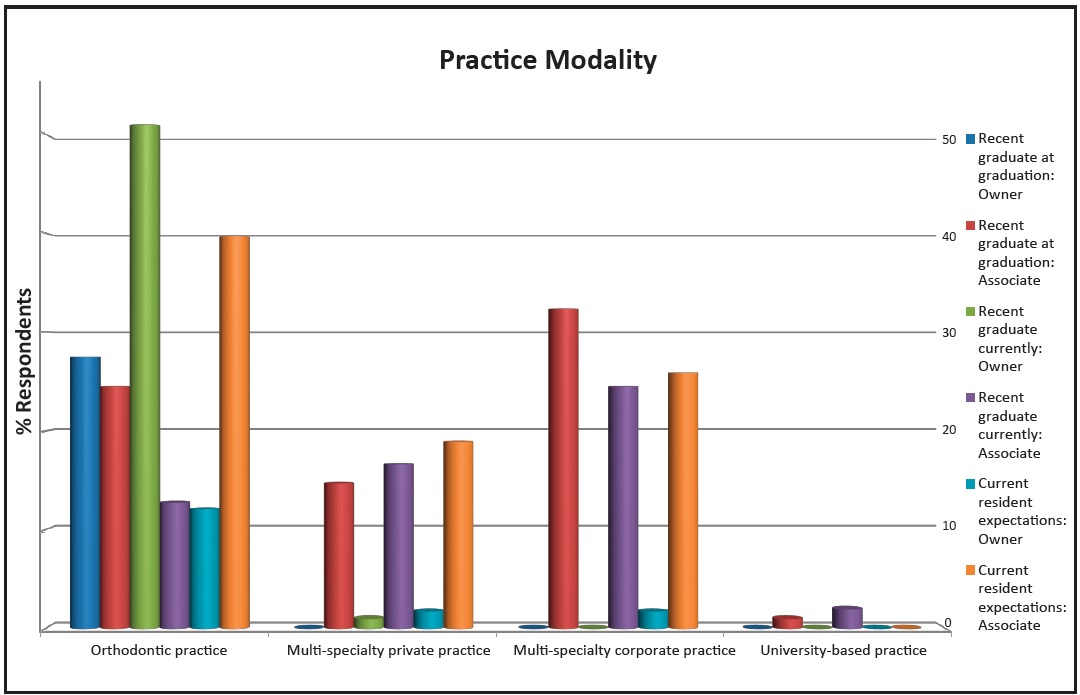

Seventy-six percent of the graduates had worked four years or less, and 75% reported an income range of $100,000-300,000 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Expected vs. actual income for graduates and residents.

Nearly half had expected to have higher incomes at this point in their careers, by an average of about $150,000. This reality stood in stark contrast to the responses of current residents: 95% anticipated earning $100,000-300,000 immediately after graduation, and 50% expected to earn $300,000-500,000 within five years.

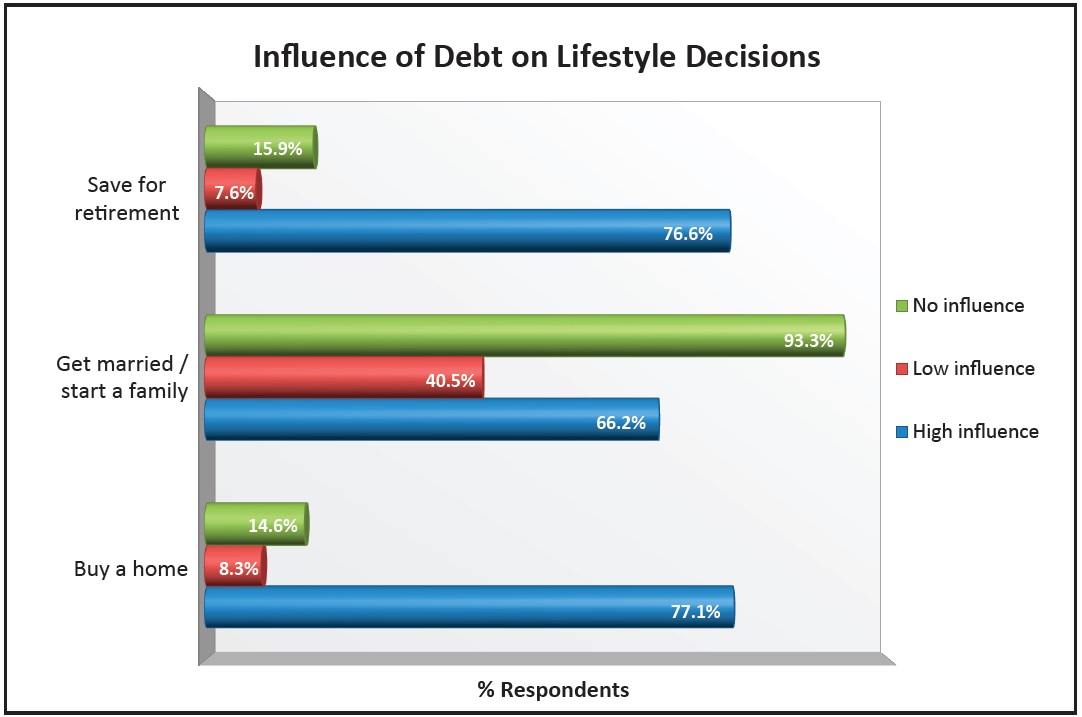

The amount of education debt had an obvious impact on the timing of other lifestyle and financial decisions, with about 77% of all respondents indicating they were unable to purchase homes or save for retirement (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Influence of debt on lifestyle decisions (combined data from graduates and residents).

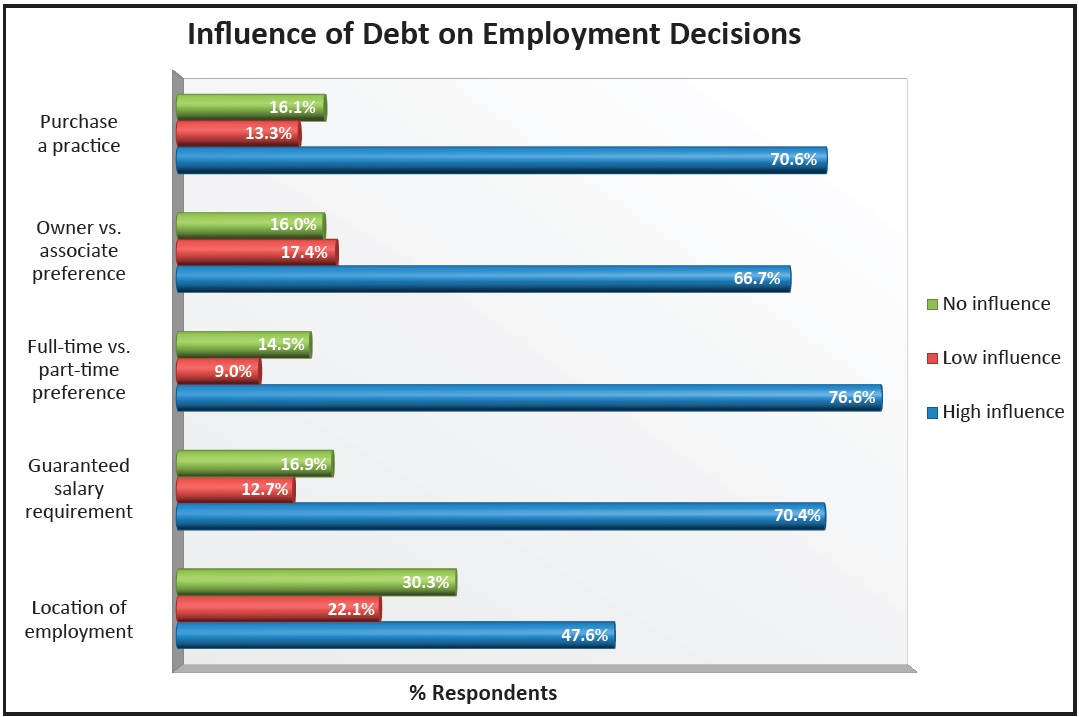

About 71% percent said their debt load had left them incapable of purchasing practices, and 67% felt their debt had greatly influenced their decision to associate rather than own (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Influence of debt on employment decisions (combined data from graduates and residents).

Among the various types of debt instruments, 86% were Stafford loans (subsidized or unsubsidized), 66% were PLUS loans, 42% were private loans, and 58% came from private sources; most residents had loans from more than one source. In terms of repayment, 54% of the graduates said they paid $1,000-3,000 per month, while 38% paid more than $3,000 per month. Thirty-two percent of the residents expected to pay more than $4,000 per month after graduation. Thirty-one percent of all respondents used or planned to use an income-based repayment option; 25% used or planned to use either standard (10-year) or extended (25-year) repayment plans. Seventy-five percent of the recent graduates reported using deferment or forbearance on their student loans. Half felt they were on track to pay back their loans on time, but 17% did not believe they could pay their loans as scheduled, mainly because their expenses exceeded their income.

Smart debt management and financial planning are crucial to the success of recent graduates. Among our respondents, 39% reported that their residency programs had offered financial planning, typically in the form of seminars. Fifty-seven percent would likely have used financial-planning services if they had been available, with group and individual financial counseling the most popular choices. Forty-three percent of the respondents said they had felt informed regarding their financing options when they entered their residency programs.

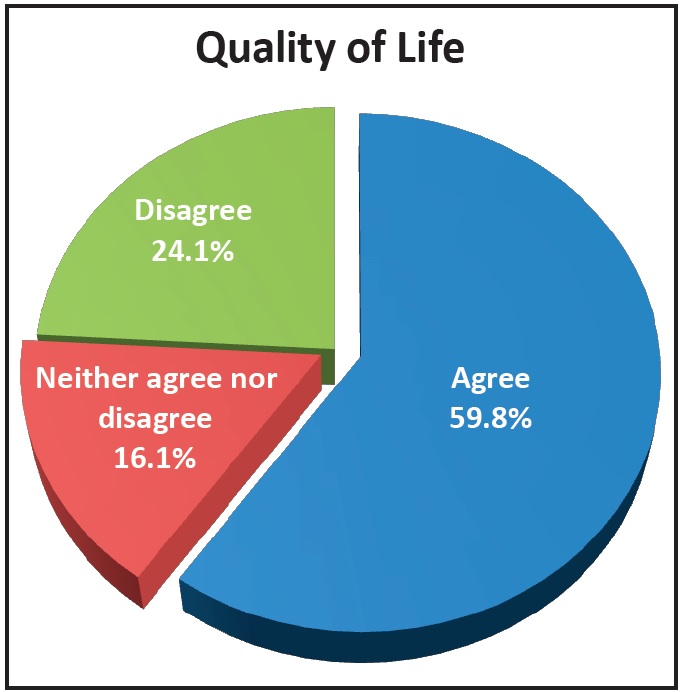

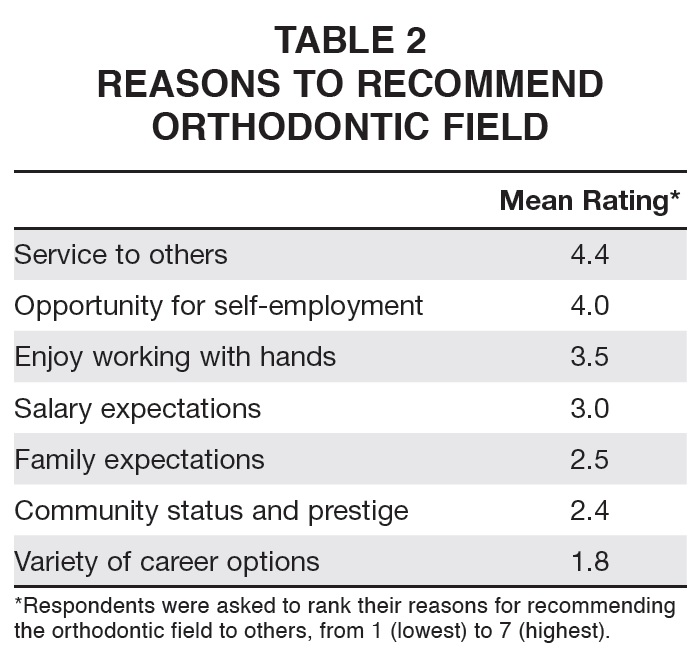

Despite the financial obstacles, 60% of the graduates agreed that they were satisfied with their quality of life as orthodontists (Fig. 6). Their primary reasons for recommending the orthodontic field were the opportunities to become self-employed and to provide service to others (Table 2). Similarly, 50% of the respondents to a 2012 survey of dental students perceived orthodontics to have the highest quality of life among nine specialties.7 Thirty percent believed that orthodontists had the second-highest incomes, just behind oral surgeons.

Discussion

The Graduate Medical Education (GME) program for non-hospital-based dental residency programs formally ended in 2006. In response, the Teaching Health Center (THC) GME program was created by the Affordable Care Act to increase the number of primary-care residents and dentists being trained in community-based settings.8

This program applies to general and pediatric programs, but not to orthodontic programs. Several loan-forgiveness programs are offered at the state and federal levels, but again, none apply to orthodontics.9 Only 9% of the respondents to our survey planned to use loan-forgiveness programs, and all of these cited the Income Based Repayment Plan - a repayment plan rather than a forgiveness program. The best alternative for orthodontic graduates is the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, which still has several drawbacks. First, the graduate has to provide general dentistry, which would not earn enough income to repay the typical debt accrued by an orthodontic resident. Second, the recipient has to make 120 qualifying payments while enrolled in the program. Although both the ADEA and ADA have advocated on behalf of GME and loan forgiveness for dentists, no viable option is available to the orthodontic specialist.

Fig. 6 Responses of recent graduates to statement, “I am satisfied with my quality of life as an orthodontist.”

The financial burden placed on new orthodontists is a significant problem that the profession must address. Just as the economic downturn affected the retirement plans of more established orthodontists,10 the ripple effects continue to be seen among those just starting their careers. Notably, there are fewer practices available for purchase as established orthodontists are extending their careers. The Practice Opportunities and Careers section of the AAO website recently listed 158 available positions and 700 registered job seekers.11 Of those 158 available positions, only 52 were practices for sale. In a 2011 editorial, Scholz observed that a resident would need to purchase an office with enough immediate cash flow to cover both living expenses and debt repayment; a satellite office with potential would not suffice.12 He suggested that sellers willing to finance these busier offices would attract more buyers.

Individual comments from residents responding to our survey highlight the impact of this debt crisis. Among their top concerns was the influence their loan debt would have on career choices as they prepared for graduation. Respondents felt that job placement would be difficult and that they would need several places of employment to achieve fulltime status. In one example, the combined household debt of married dentists who were both in a residency program surpassed $1 million. They were well aware of the financial difficulties they would face as they started their careers. Another resident expressed uncertainty that student debt could be completely repaid within 20 years, considering the compounded interest and monthly payments.

Recent graduates offered some advice and perspective, with mixed success in terms of loan repayment. One respondent reported paying off the loans within two years by choosing a less populated area with more need for an orthodontist. Another admitted that the current salary level would have been sufficient in a state with a lower cost of living. Several respondents suggested asking for help from orthodontic associations to address student-loan debt and income instability. One graduate mentioned having been told in dental school to apply only to residency programs that would be "affordable". Nearly half of our respondents cited tuition as a factor in selecting their programs. Unfortunately, this tendency may leave the specialty unable to attract the best-qualified future residents, as opposed to those most able to pay tuition.13

The PCSO recently mailed a survey to all orthodontic program directors within the region regarding the information on financial planning offered to their residents. All the directors who responded agreed that debt load and repayment were significant issues and that more could be done to support residents in meeting these challenges. Many said they offered practice-management courses, which tended to focus on association agreements, transitions, and office management, with little emphasis on personal finances; few offered true financial planning or debt education. Although individual faculty members can give advice, they might not be qualified to handle the significant debt issues facing residents. The challenge is to provide an unbiased outside source to address these issues on a personalized basis. Most respondents to our informal survey were receptive to the idea of a financial-planning course, in either a group or individual setting. Since the financial needs of each resident are unique, one-on-one sessions would be most beneficial for personal budgeting and debt reduction, while group sessions at national meetings could be useful in addressing common issues faced by graduates. Panel discussions among peer groups could alleviate some students' anxiety about all-encompassing debt loads.

Management of expectations regarding realistic income, repayment options, and budget analysis is imperative for new graduates. More than 70% of our respondents felt that their student debt had affected their ability to buy a home, save for retirement, or purchase a practice. This situation affects not only the dental profession, but the community at large. The trend among health-care professionals toward delaying major life decisions is bound to continue, and the long-term impact on the economy has yet to be determined. Postponement of retirement savings may certainly result in less turnover of orthodontists who are reaching retirement age, further exacerbating the saturation of graduates seeking employment.

Limitations of our study include a low response rate, narrow geographic distribution, and selection bias. Some addressees may have chosen not to participate because they had little to no student-loan debt, skewing the results toward a higher average debt. In a climate where high student-loan debt is a hot topic, residents with limited loans may have been hesitant to share positive experiences. In addition, our survey included areas with a higher overall cost of living, which may have inflated the relative impact of tuition and living expenses. The PCSO region has a higher density of orthodontists, which may reduce both owner-orthodontist incomes and associate wages compared to other regions. It may also limit the number of practices available for purchase, restricting more graduates to associate positions. An expanded study on the national level would provide a more accurate representation of total debt and income levels. Extension of the survey beyond orthodontics would paint a broader picture of the financial burden of the dental profession and specialties as a whole. Finally, a comparison of debt for residency programs with and without GME stipends would be informative.

Long-term ramifications of high student-loan debt are yet to be determined. Dental students and residents may continue to overextend themselves financially, since that is perceived as the new norm. The results of this survey should be a cautionary tale, not a justification for increasing indebtedness.

Conclusion

Our survey suggests that student debt is a great concern to the new generation of orthodontists, and that the size of their loans significantly affects career and lifestyle decisions. Despite these concerns, orthodontics still ranks relatively high in terms of both quality of life and salary. Orthodontics can remain among the top specialty professions as long as debt management is a priority in career planning. Although debt education should start at the dental-school level, it is never too late for students to consider it. It is the responsibility of professional organizations, educators, and practicing orthodontists to guide new professionals through the obstacles they face.

We offer the following suggestions to better educate and prepare residents as they enter the workforce:

• Association advocacy to include orthodontics in both THCGME funding and the Dental Faculty Loan Repayment Program, or to provide other student-loan forgiveness programs for orthodontists, in conjunction with ongoing efforts to control student-loan interest rates and tuition increases.

• Annual-session programs geared toward financial planning, including optional one-on-one sessions, group seminars, and question-and-answer panel discussions involving new and established practitioners.

• Stronger practice-management seminars within every residency program, preferably within the last six months of the curriculum, to review employment choices, contracts, and practice financing.

• Two to three association-sponsored, unbiased financial-planning sessions during residency. The first session, scheduled upon acceptance to a program, should assess current debt load, options for financial aid during residency, and projected repayment terms, along with post-graduation income projections and advice on establishing personal budgets. An optional mid-residency session should reevaluate and update goals and expectations. Session three, around graduation time, should review repayment options, projected repayment terms, income forecasts, and personal budgets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The authors would like to thank the PCSO Board of Directors and staff for their support with this project and Dr. James D. Seward for assistance with the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Dental Association: Distribution of dentists, www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/publications/survey-report-archives, accessed July 28, 2015.

- 2. American Association of Orthodontics: Accredited orthodontic programs, www.aaoinfo.org/education/accreditedorthodontic-programs, accessed July 1, 2015.

- 3. Garrison, G.E.; Lucas-Perry, E.; McAllister, D.E.; Anderson, E.; and Valachovic, R.W.: Annual ADEA survey of dental school seniors: 2013 graduating class, J. Dent. Ed. 78:1214-1236, 2014.

- 4. Noble, J.; Hechter, F.J.; Karaiskos, N.; and Wiltshire, W.A.: Motivational factors and future life plans of orthodontic residents in the United States, Am. J. Orthod. 137:623-630, 2010.

- 5. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Occupational employment statistics, www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291023.htm#(2), accessed July 31, 2015.

- 6. Overcash, C.: Residents’ survey, Orthod. Prod., Aug. 6, 2014, www.orthodonticproductsonline.com/2014/08/residentssurvey, accessed July 2, 2015.

- 7. Dhima, M.; Petropoulos, V.C.; Han, R.K.; Kinnunen, T.; and Wright, R.F.: Dental students’ perceptions of dental specialties and factors influencing specialty and career choices, J. Dent. Ed. 76:562-573, 2012.

- 8. Health Resources and Services Administration: Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME), bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/teachinghealthcenters, accessed July 31, 2015.

- 9. American Dental Association: Dental student loan repayment programs and resources, ebusiness.ada.org/assets/docs/2312.PDF?OrderID=645534, accessed July 31, 2015.

- 10. Sturgill, J. and Park, J.H.: Changes in orthodontists’ retirement planning and practice operations due to the recent recession, J. Clin. Orthod. 49:240-248, 2015.

- 11. American Association of Orthodontics: Practice opportunities and careers, www.aaoinfo.org/careers, accessed Aug. 7, 2015.

- 12. Scholz, R.P.: Orthodontic education—The times they are a changin’, Angle Orthod. 81:1111-1112, 2011.

- 13. Turpin, D.L.: Debt: A fact of life for postgraduate students, Am. J. Orthod. 132:275-276, 2007.