THE EDITOR'S CORNER

The Complexities of Partial Treatment

The subject of partial treatment comes up frequently in both the orthodontic literature and day-to-day practice. While the main focus of our clinical activities is always on comprehensive treatment of both growing and non-growing patients, situations inevitably arise that call for only partial treatment. Examples include palatal expansion when the only manifestation of malocclusion is a posterior crossbite, tipped molars that require uprighting prior to prosthetic restoration of adjacent edentulous spaces, and single-tooth crossbites. These corrections are frequently referred to as "minor orthodontic tooth movement".

I must say I cringe every time I hear that phrase, remembering the voice of one of my former colleagues in the University of Tennessee Department of Orthodontics: "There ain't no such thing as 'minor' orthodontics!" To perform any tooth movement, the orthodontist must have an intricate understanding of the physiology of tooth displacement and the biomechanics of forces, moments, and vectors, along with a firm footing in patient management. This is true whether we are moving one tooth or guiding the growth of an entire orofacial complex.

Similar articles from the archive:

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER Primum Non Nocere April 2008

- THE EDITOR'S CORNER More on Limited Treatment September 2005

In some ways, partial orthodontic treatment is actually more difficult than comprehensive treatment from the clinician's point of view. Any orthodontist who has been in practice for more than a few years has developed preferred treatments for each of the major categories of malocclusion. All Class I crowded cases that come through the office will be treated essentially the same, allowing for the minor variations that make each and every case unique. The same holds true for Class II and Class III treatment. Psychologists refer to this phenomenon as "chunking"--it's a hallmark of someone who has achieved the status of "expert". But one of the salient differences between partial and comprehensive treatment is that most cases requiring partial treatment do not lend themselves to stock procedures. In other words, the expert cannot always "chunk" in these situations; treatment plans, procedures, and appliances frequently have to be individualized for each case.

Granted, there are some situations involving "minor tooth movement" that can be standardized. For example, probably 90% of the growing patients I treat who need maxillary transverse expansion are handled in roughly the same way: apply a rapid palatal expander, correct the crossbite, then transition to full fixed appliances if the situation calls for it. Most partial treatments, however, do not lend themselves to standardization. I don't think I have managed tipped-molar cases the same way twice. The individualization required to treat such cases is so disruptive to the flow of a busy, high-volume operation that several of my friends have deemed it better to refer them to colleagues with slower-paced, "boutique"-style practices.

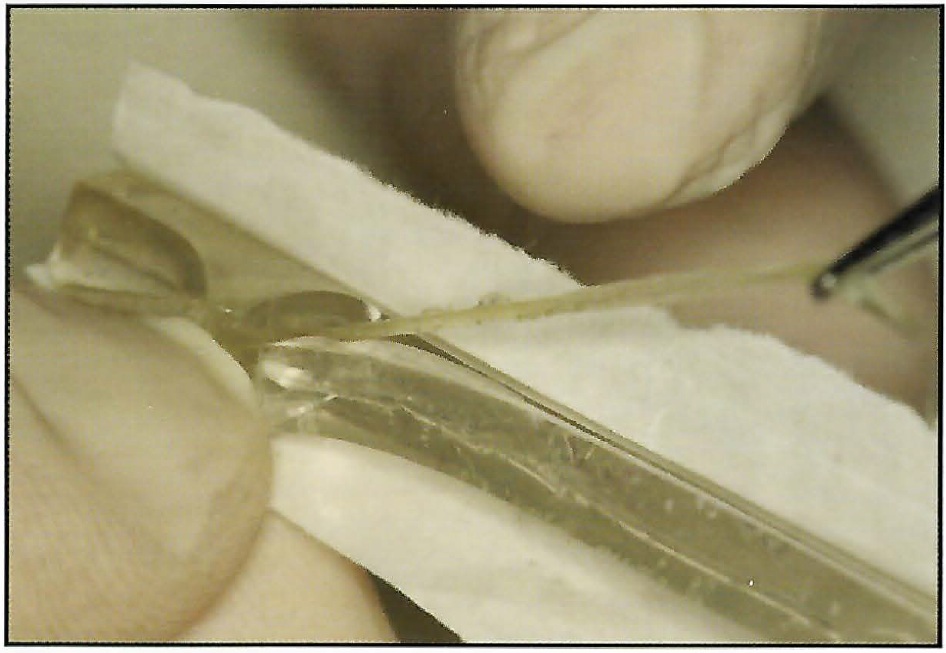

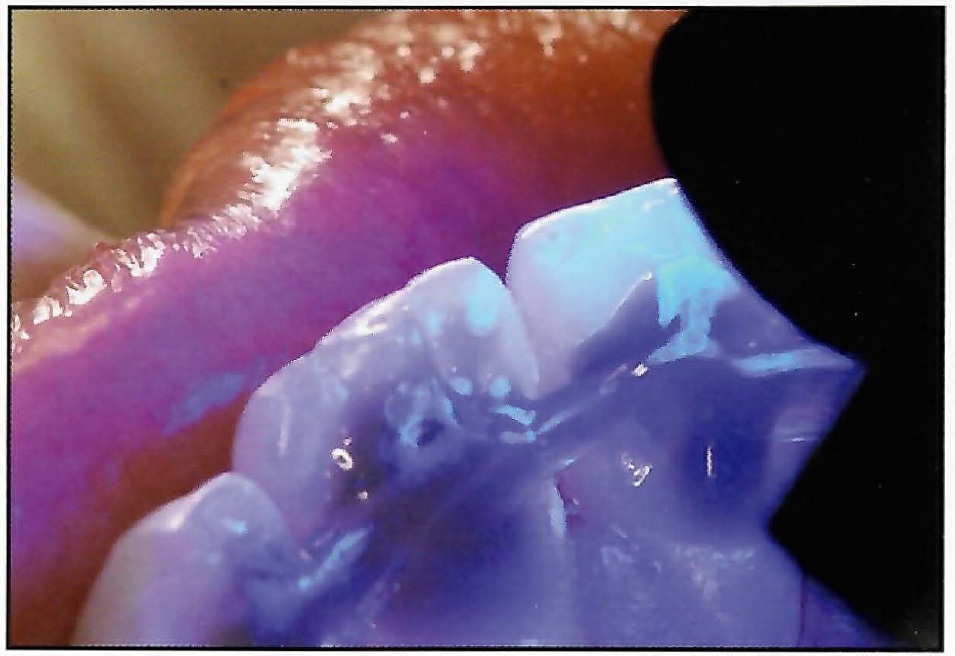

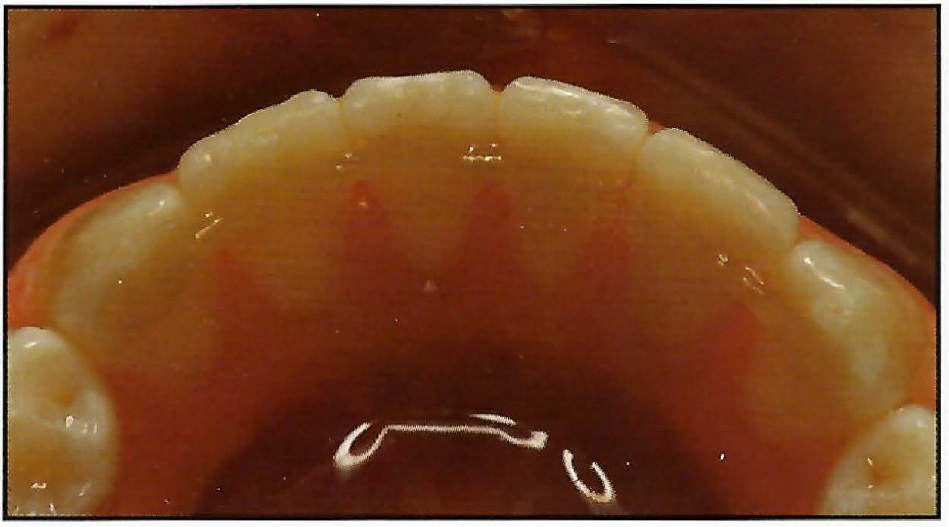

One of the most frustrating types of partial treatment is the forced eruption of fractured teeth. This kind of case usually requires endodontic treatment prior to eruption. If the tooth was not in proper position before the fracture, it will not only have to be erupted, but will also have to be repositioned before final restoration. And where there is not enough of the clinical crown left to allow bonding a bracket, some way of connecting an attachment to the tooth must be devised for eruptive force application. To further complicate the issue, even if we are able to erupt the fractured tooth to a vertical level high enough to provide sufficient margins on a crown, we may still have to esthetically recontour the labial gingival crest and maintain an acceptable crown-root ratio. Again, individualization rather than standardization is the rule.

In this month's issue of JCO, Dr. Ansari and colleagues present a partial-treatment case involving two fractured teeth--a maxillary central incisor and its adjacent lateral incisor. One had enough crown left to attach a bracket, the other did not. By employing an individualized treatment approach, the authors were able to accomplish the dual goals of appropriate crown-root ratio and pleasing gingival esthetics, and they produced an entirely acceptable overall occlusion. Although each of us has treated similar cases, I sincerely doubt that any of us has treated them in exactly the same manner. There are many possible ways in which these fractures could have been handled successfully, but the authors' approach is unique, and the results are self-evident. We can all learn something from reviewing this case.

RGK