Every March 14, mathematicians celebrate the concept of pi--the number you get by dividing the circumference of a circle by its diameter. The chosen date, 3/14, is derived from the value of pi, 3.14. Of course, the number stretches out to the familiar 3.1416 and well beyond. Ad infinitum, as a matter of fact. It is what the Greeks called an irrational number, because it is not determined by simple division, and since you cannot ever arrive at the value to the last decimal place, even 3.14159265 is an approximation. Someone calculated that pi may become known to the 51 billionth digit. How one would use that data has not yet been determined.

Although orthodontists are not often concerned with the value of pi, it is commonplace to see measurements in orthodontic research carried to two decimal places, or to hundredths of a millimeter. To keep things in perspective, the difference between 1.14mm, rounded to 1.1, and 1.16mm, rounded to 1.2, is .1mm. That's .0039 inches.

What are the practical limits of linear and angular measurements in the mouth? They should be judged by two factors: the accuracy of the measuring instrument and the precision needed. As the accuracy of our measuring tools improves, it becomes apparent that we can measure more accurately than clinical orthodontics requires, at least under the present state of the art. The crudest of the measuring instruments, and the one we use the most, is the human eye. With the eye alone, an orthodontist can bring teeth into a reasonable occlusion, appearance, and stability. More accurate tools such as cephalometric measurements may set goals and help determine if they have been reached, but the eye is the primary judge of treatment success.

Similar articles from the archive:

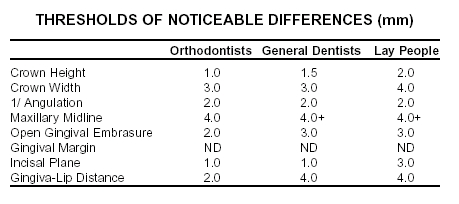

A recent study compared the points at which dentists and lay people perceived a noticeable difference in incrementally altered dental esthetics.1 The results were as shown in Figure 1.

The table shows that the orthodontists' collective eye, while uniformly more sensitive than that of general dentists and lay people for the changes studied, was oblivious to 1mm of change in some perceptions and as much as 4mm in others. This sets a kind of standard for the "orthodontist's eye" as a measuring instrument and suggests that whole numbers should suffice for clinical purposes.

We frequently see studies comparing bonding materials in which results are carried to two decimal places and the differences among them may be found to be statistically significant. These studies may be important in evaluating and comparing the characteristics of various adhesives, and they must be viewed in light of their objectives. Nevertheless, they highlight the difference between academic research and clinical practice. In bonding studies, regardless of measurable or even significant differences in research results, all the materials evaluated may be adequate for the designated clinical task. Furthermore, the strongest bond may not always be the best bond; it may make debonding unnecessarily difficult and even destructive to surface enamel. Because the studies are not always able to isolate one independent variable, it may be a stretch to extrapolate from in vitro to in vivo. The success rate in the mouth may be strongly related to bonding procedures in a particular office. So while lab testing has its virtues, the ultimate test for the clinician is what works in your office.

In cephalometric analyses we make distinctions that are no greater than the error in identifying points or than the thickness of the pencil used for tracing. The possibility of error in drawing, even in how you hold your wrist, and in measuring angles may be greater than any discernible difference. Yet there is comfort in numbers, especially if they can be shown by some test to be statistically significant.

Should we give up precise measurements? Of course not, but we should use numbers in proper context, and in many cases give the clinical priority over the statistical.

ELG

REFERENCES

- 1. Kokich. V.O. Jr.; Kiyak, H.A.; and Shapiro, P.A.: Comparing the perceptions of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics, J. Esthet. Dent. 11:311-324, 1999.