How Are We Doing?

Phoebe Lee Grisham, my maternal grandmother, was a remarkable woman. Widowed in her early 50s, she finished raising a brood of 11 children, took charge of four orphaned grandchildren, and provided refuge for a widowed daughter and her two children. Phoebe inherited a 200-acre North Texas farm from her husband, and she kept it going by raising cotton and corn throughout the Great Depression, even while neighbors all around her were going broke.

Today, my magnificent "Me-Ma" couldn't even ante up in the farming game, much less survive and prosper. Technological advances have made farming much less labor-intensive and more productive, but have also resulted in much greater capital requirements. Whereas you could farm through the 1930s with a couple of mules and a plow, nowadays you must have a tractor with an air-conditioned cab and at least 2,000 acres.

Of course, technology cuts both ways. The laborsaving implements that greatly increased the productivity of the remaining farmers also produced a surplus of agricultural commodities, driving down their prices. To maintain the same relative standard of living, U.S. farmers (now 3% of the population vs. more than 50% in the 1920s) have had to farm more land, borrow more money, produce more, and sell more-- then compete with others who were doing the same thing. In a global economy, the economic pressures only increase further. Farmers have begun to feel like Lewis Carrol's Alice, who was told she had to run faster just to stay in the same place.

The 1993 JCO Orthodontic Practice Study indicates that orthodontists have been suffering from an economic dilemma much like that of the farmers. Productivity has increased in our offices because of a convergence of improved technology and expanded use of auxiliary personnel. The median gross income of orthodontists has more than doubled over the past 12 years, which may seem satisfactory until one notices that median overhead increased from 49% to 56% during the same period. Median active cases did move upward in 1992 for the first time since the 1983 Study, but only by 4%. While the consistent increases in gross and net income are somewhat reassuring, they paint an incomplete picture, leaving out the problem of an eroded standard of living.

The only realistic way to evaluate a price or fee over time is to relate it to a common denominator, such as the average hourly wage. In 1952, the average hourly wage was $1.62; in 1992, it was $11.45. Thus, the average 1952 wage earner had to work 432 hours to purchase orthodontic treatment, which then cost about $700. In 1992, he average laborer expended only 279 hours to purchase a child's orthodontic treatment costing a median of $3,200. For orthodontists, that represents a 35% reduction in fees. Had orthodontists adjusted for wage inflation since 1952, the average fee today would approach $5,000.

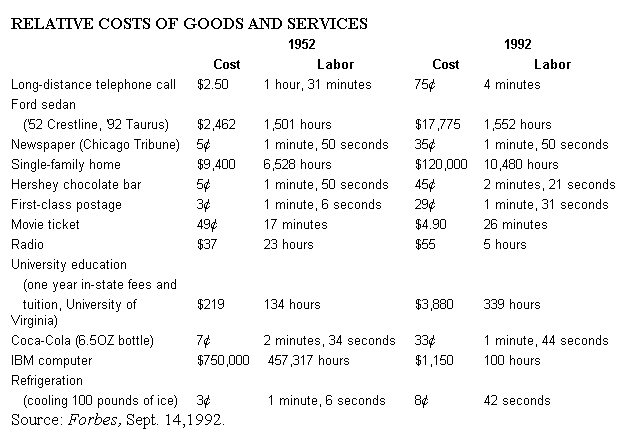

To focus on this point, we need only look at how the prices of many common goods and services have changed over the past 40 years (Fig. 1). Labor-intensive commodities-- particularly in fields controlled by unions and strong labor cartels, such as education, industry, and construction-- have more than kept pace with inflation. Like other technologically driven goods and services, however, orthodontics is a better value today than ever before.

Of course, price alone can't measure the value of a professional service; certain subjective features defy quantification. For instance, how can you compare the comfort and efficiency of today's bonded brackets and low-force wires with the bands and crowbar forces of yesteryear? The difference is noticeable enough that more patients than ever seek orthodontic treatment, but it's difficult to measure.

In any event, it appears that orthodontists are stuck with the predicament of having to increase fees to keep pace with inflation, while simultaneously improving productivity and lowering overhead, just to prevent further relative deterioration of their living standards-- not an easy job considering the increasing intervention of such third parties as insurance companies, preferred provider organizations, and government bureaucracies.

I think orthodontists will persevere and the profession will emerge from this persistent economic tribulation even stronger and more respected, but I anticipate changes in the delivery of orthodontic services within the next five to 10 years that will make the last 20 seem like slow motion. Economically and professionally, the near future offers more challenge and excitement than any era in memory.