DR. BARNETT Pat, how are practicing orthodontists going to make use of computer technology that is on the horizon today?

MR. TRACY Jay, the explosion in computer technology is made up of a combination of factors:

1. More powerful multi-user, multi-tasking operating system software that will absorb input simultaneously from different work stations and respond instantly with visual and audible output.

2. Interfaces that will eliminate most of the troublesome--and labor-intensive--"keyboarding" that plagues the systems of today.

3. Electronic forms that will be stored magnetically on the hard disk, called out automatically by the program, merged electronically with the printed data, and imaged on paper by a laser printer (including the logo). The old-fashioned, costly preprinted forms will become a thing of the past. This applies to stationery, statements, payment coupon books, treatment plans, accounting reports, letters, appointment slips, and more.

4. Simplistic systems designs that will shorten the learning curve for practice personnel and dramatically reduce the training hazard of personnel turnover. This is due to the sharply declining cost of memory chips, which limit the size of computer programs. And the most welcome news is that it will ail be in graphic form. The endless streams of numbers on paper, so characteristic of today's systems, will be a thing of the past--they will be supplanted by charts and graphs. Artificial Intelligence techniques boasting a knowledge base of the practice will devour the more mundane decisions--leaving the more important items for human intelligence.

DR. BARNETT Won't these sophisticated systems be more complex for the user?

MR. TRACY I am describing systems that will be so utterly simple that non-accountants will be able to input complex accounting data without any idea about how double-entry bookkeeping works, and so simple that no typing skills will be necessary to run the word processing. The computer can type, so we can begin to let it compose as well as type the letters. The programs will trigger letters automatically--filling in the variables where they belong in the letters to make most communications completely automatic operations.

DR. BARNETT What breakthroughs are making this possible?

MR. TRACY There have been so many advances in information systems technology in the last few years--not only in systems design, but in the integration of hardware and software--that the small, 32-bit IBM desktop computer (PS/2, Model 80) that you can afford in your office today is the equivalent in raw power to one sold by IBM in 1975 for $3.5 million (an IBM System 370, Model 168). That computer had to have chilled water plumbed in to keep it cool, occupied a large computer room requiring strict environmental controls, and consumed large amounts of electrical energy. This was not only the top of IBM's line, but the most advanced large-scale mainframe that you could buy back in 1975.

The trick in the late 1980s is to harness this power in an effective manner by utilizing fourth-generation, non-procedural languages, as opposed to the current practice of using outmoded procedural languages such as COBOL and BASIC. These languages are expensive and time-consuming to program and require monumental amounts of time to maintain.

DR. BARNETT What do you visualize this multi-user, multi-tasking environment will do for us?

MR. TRACY Multi-user means that you have a number of people in the practice who are simultaneously sharing a common data base. Multi-tasking means that one user on one work station can process several tasks simultaneously at high speed. Let's say that the bookkeeper wants to look at a payment history while on the telephone. At this same instant, treatment plans are being examined and treatment is being posted to patient charts in the operatory, while again at the same time, the receptionist is booking patient appointments. I will give my first piece of advice--don't try this scenario with present systems, particularly those utilizing keyboards as the primary means of recording data.

To grasp the dramatic changes in operating systems that have occurred in the transition from 8-bit machines to the present 32-bit machines over the past 10 years, refer to the table (Fig. 1). The 32-bit processor on the far right has the capability of performing admirably in a multi-user, multi-tasking situation, but it takes something like XENIX (UNIX), which is a multi-user operating system, to permit you to share a common data base. An MS DOS or OS/2 operating system would never be capable of doing these things for an orthodontist. Unlike a commercial enterprise--which is neatly cordoned off into departments like accounting, marketing, sales, and manufacturing--the orthodontic office revolves around a central patient data base.

DR. BARNETT So you're saying that my current office system is quickly becoming outmoded?

MR. TRACY I think that it is important to consider how far information systems provided to orthodontists have progressed from the early 1970s up to this point--and in many cases at tremendous expense and effort to the pioneers. Take your situation, for instance. You started out with an IBM mag-card Selectric typewriter for your letters and an IBM System I for your accounts receivable. Then you replaced that with an IBM System 23. These "ancient" machines seem very slow and cumbersome compared to the affordable machines of today. Back then you did not expect to have a total practice information system-- you just wanted to accomplish your billing and speed up your letters.

The floppy disks (which were great at the time) could never have accommodated a modern large-scale relational data base, nor could the small amount of expensive random access memory handle the large programs of a total information system.

DR. BARNETT Pat, what do you think would be the ideal setup for the orthodontist within the next five years? What would be possible and practical within the orthodontic office?

MR. TRACY What I see is an information system that ebbs and flows as the practice does. When you're seeing patients, information flows semi-automatically into the charts that are contained on the hard disk, flows in and out of the accounts-receivable file, and in and out of the appointment book for the scheduling of practice resources. The watchword of these kinds of systems will be simplicity. A person who comes to work in the practice in a given occupation should, within a week or so, be completely trained and competent to interface with the system--whether it's the receptionist who's booking appointments, or the bookkeeper who is posting the payments to accounts receivable or making the bank deposits.

Scheduling of patient appointments will improve dramatically when you are able to insert all of the future appointments contained in long-term treatment plans for all active patients, 36 to 48 months in advance. Then you will begin to see where the gaps are going to come in the appointment book, where you need to plug in those new starts, and when you need those new starts to begin treatment. When you base the appointment schedule only on the current population and you only look three to six weeks in advance, you really don't have time to react to that kind of a schedule change. Now, for the first time, you will be scheduling with accurate data according to your future practical capacity.

Simplicity provides protection against errors, whether inadvertent or otherwise. When an employee leaves and is replaced by a new one, the learning curve will be absolutely minimal. This system will necessarily be organized according to the job descriptions, not organized from a functional standpoint as are most of the menu-oriented systems of today. Menus based upon function rather than job description are confusing, to say the least. The system as I see it should ask what you want it to do. If you want to perform a task the receptionist normally does, you should go to the receptionist work station. It will not matter that the practice may be small enough that your receptionist is also your bookkeeper. The point here is that bookkeeping and reception activities should not be all intertwined or commingled in the menu structures.

DR. BARNETT Will there be a reduction of labor cost as a part of what we can expect to happen in the future?

MR. TRACY Yes. Most of the systems today are labor-intensive. In other words, you have to put in 10 pounds of input to get 1 pound of output. So you have a lot of keyboarding to do. For instance, when you enter into a contract for 24 or 36 monthly payments, you know that in advance. There's no need to pound 36 payments into the keyboard, one a month, for the next 36 months. You might instead use a laser printer to print up coupon books with bar codes on them. Then it is just a matter of running a wand over the bar code on the coupons when the patients send them in with their checks. This captures the data automatically, plus there's no room for error and it doesn't require skill. The wand works the same as the laser scanner you have seen in the grocery store. The laser reads that bar code label, looks up that item in the inventory file, and lists it on the cash register. In your practice, by moving that wand over the bar code you have accomplished two things. You've prepared your bank deposit, and you've credited that payment to accounts receivable. And you have done it with lightning speed and with complete and total accuracy.

DR. BARNETT Are you saying that the orthodontist can reach the point where bookkeeping can be done on a part-time basis?

MR. TRACY That's right. Let's say in a very large practice one person can wand in an hour what would normally take a whole day of keyboarding. Not only would you have a speed factor of 10 or 15 to 1, but there would be no comparison from an accuracy standpoint because your errors in wanding approximate one in 10 million characters captured. Keyboards produce a minimum of one error in 100 keystrokes.

This bar-code scanner is not necessarily limited to the recording of payment coupons. Once you establish a treatment plan for a patient that goes over x number of months, you know in advance exactly what services you're going to perform and when. With a little imagination, it is easy to visualize that it is just a question of wanding in the procedures as they are done. Exceptions will be accomplished otherwise, but these probably occur only 15-20% of the time.

The picture that is evolving is one of capturing all the data for the charts, all of the data for the financial accounts, and all of the appointment data. To my way of thinking this is a much better way than having typists keyboard the data. The other means of eliminating labor is to use devices such as a mouse or a touchscreen. These devices eliminate the need for typing capabilities and use approaches that are very akin to human nature.

DR. BARNETT What do you mean by that?

MR. TRACY Well, a child starts pointing a finger at a very early age. Imagine having a CRT screen in the operatory that approximated a schematic of the mouth, with some buttons drawn on the face labeled "banding" and "bonding" and so forth. Entering this data becomes a matter of touching those buttons and posting that to the chart. In the war zone of the operatory, it's difficult to plant a keyboard device, and you don't really want to increase the amount of paper. Most systems today require you to fill out numerous forms and pieces of paper and then dump them into big baskets on a typist's desk for keyboarding. Suddenly these methods become extraneous and old-fashioned.

DR. BARNETT What would be the value of recording in electronic form the actual treatment that occurred on each visit?

MR. TRACY When you design a treatment plan that carries with it a certain fee, you assume a certain profit on that fee. Now, we know we live in the real world, where there are going to be broken and missed appointments, broken appliances, poor toothbrushing habits, and so on. Also, there are going to be some variances in cooperation as well as people who don't pay the fee. These are the reasons that you need to compare the actual happenings in the practice with what you planned to happen when you took the case. If you had a system that permitted management by exception, you would look at the ones that aren't profitable and then try to analyze the reasons. Is this a problem in our operatory? Do we need better training in banding or bonding? Or is it certain kinds of malocclusion?

DR. BARNETT How is all this instantaneous information going to help us bring in more patients?

MR. TRACY In today's market, you need to know what factors are affecting your practice, both pro and con, and take these into consideration in your planning for profit. You need to react fairly quickly. If you have the right information system, you can project what your new starts will be, how much income these patients will provide you, etc. From this information, a mathematical model of the practice can be built. By entering different numbers of starts at different fee schedules, in conjunction with different levels of active patients, you can determine the financial effects of implementing various strategies before the fact. One conclusion could be that you raise your fees and take in a smaller patient population. That may be more desirable than trying to increase the number of patients by lowering your fees.

What I'm trying to emphasize here is that the primitive information systems of the past provided only sporadic information that is not readily available or not available on an ongoing basis. If these systems are not very comprehensive about details on treatment as well as finance, then they must be replaced.

The most important factor in an information system is the accuracy of the information--the integrity of the data base. The second most important aspect is the timeliness of the information. If you get the information two or three weeks late, chances are it's too late to do anything about it. Then there is the principle of management by exception. There is no reason with the state of computer technology today for an orthodontist to look at reams and reams of paper to find two or three nuggets of information. The system should print out bare-bones, minimum information--only the exceptions.

DR. BARNETT What would be an example of an exception?

MR. TRACY As I understand it, it has been customary to send statements to every patient who has a balance. But not everybody wants a statement. When you give them a coupon book and a payoff schedule in lieu of a statement, they are able to record their payments on the stub and check the payment off. This saves you the cost and effort to print, fold, stuff, postmark, and mail hundreds of statements each month. By using the principle of management by exception, you now only mail statements to those accounts who either had a miscellaneous charge of some kind outside the contract, or who are delinquent in their contract payments.

Most people make decisions based on what they know in the present and what happened in the past. If you have a good information system, you can take that third item into consideration--the future. This permits you to take corrective action now to start improving your marketing techniques, to start a training program to lower your labor costs, to buy some new equipment where it needs replacing. Whatever the problem might be, it can be pinpointed by looking at your projections and seeing the trends. Of course, it's also obvious that you don't want to hire three more people to keep track of all this new information.

DR. BARNETT Pat, what conclusions can an orthodontist draw from these predictions?

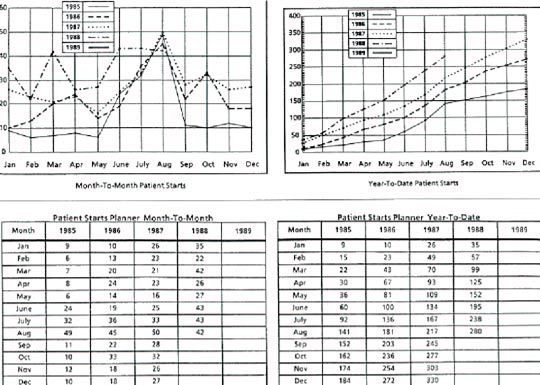

MR. TRACY As I see it, the critical aspects of today's successful practice are finance and marketing. These tasks have always been intimidating to orthodontists, whose primary training and skills have been in diagnosis and treatment of patients. Also, it is unrealistic to believe that the average practitioner can afford professionally trained accountants and marketers on the payroll. The answer to this dilemma lies in the future computer system, which will automatically produce a month-by-month history of patient charges, contract payments, starts, delinquency, expenses, and profits for the past four years, in both numeric and graphic form (Fig. 2). The orthodontist can then estimate the figures for the next year and determine whether to increase starts, raise fees, reduce delinquency, or trim expenses.

Orthodontic computer systems of the future will resemble those formerly affordable only by large corporations. Not only will they drastically reduce the clerical skill and time required to maintain them, but they will assimilate a "knowledge base" about the practice and translate this information into the more workable form of charts and graphs to improve decision making. Thus, the long-sought goal of "simplifying complexity" through computerization can finally be achieved.