JCO ROUNDTABLE

Reminiscences of the '30s

DR. WAHL The 1930s were a time of great change in our profession. Graduate courses were being introduced in the universities; fullbanded treatment was becoming fashionable; cephalometric radiography was finding clinical applications; new materials were coming into use. You could say that the '30s marked the beginning of modern orthodontics.

It was also the time when I grew up. While you gentlemen were pinching bands, I was pitching pennies. My first recollection of braces was that only the rich kids had them. My second was that I wanted no part of them. Never did I think I would end up as an orthodontist.

Back then, marketing was something you did at the neighborhood grocer's. But for dentists getting out of school in the year of the 1929 stock market crash, there were pressing economic concerns. What was it like getting started in orthodontics then? What was your educational preparation?

DR. MUCHNIC When I graduated from USC in 1929, the only exposure we had to orthodontics was a course given by Dr. James McCoy. None of the courses at the time was longer than six weeks, as far as I know, except the Angle course.

DR. SIDLOW At that time the University of Michigan took only one orthodontic student per year, and it wasn't me. So I had to apprentice myself to another doctor. I was more or less a lab boy, but I could take one or two cases--patients who didn't know I was inexperienced. I was paid very little. Every time he had a good month, he'd give me a check for, say, $25.

DR. WAHL Dr. Farber, you went to school at NYU, trimming models by hand for Dr. Martin Dewey. In 1934 you started working for your uncle, Dr. Abelson. What did you do as a preceptee in his office?

DR. FARBER I did all the labor. I did the banding, made the appliances, took the impressions, and trimmed the models. What I got in return was free office space. You see, they had what was called a "clinic" practice. In the morning the fees were lower than in the afternoon. The low-fee treatment was more impersonal. In the afternoon, I had a small office for my own patients. That's how I developed my practice.

Remember, that was during the Depression, and orthodontics was still a big luxury--at least it was in the East. When I started practicing in Hollywood in 1942, within six months I had a bigger practice than I had had in New York after six years. The economics here in California were much better. And when I opened in the Hollywood Professional Building, there were several dentists in there who had been upset with extractions; since I was still basically conservative, they found my work attractive.

DR. WAHL In 1934, only 14 of the 91 specialists in New York City and Brooklyn had been trained at university-affiliated schools,1 and only six universities had graduate orthodontic departments.2 Most orthodontists were trained by preceptors or in a proprietary school such as the Angle, Dewey, and International schools3 (Fig. 1). Dr. Gawley, you are the only graduate of a university orthodontic program in our group. How did you start out?

DR. GAWLEY I practiced general dentistry in northern Ontario for 15 years. For five of those years I practiced with a foot engine. When I started at SC, the orthodontic program was one year, going 5½ days a week; or you could take a two-year course half time. Dr. (Spencer R.) Atkinson was head of the department, with Dr. (C.F. Stenson) Dillon second in charge. There weren't many specialists then in small towns. As far as I know, I was the first specialist in Alhambra, outside of an eye-ear-nose-and-throat man. But since I was on the staff at the University of Southern California, any patients coming into the school who lived anywhere near Alhambra had no chance of getting treated at the clinic. They had to come to me!

DR. SIDLOW In the late '30s I took a two-week course at Columbia under Bob Strang. It was a very sad course, because we realized that we were finishing cases that were failures. I could show a case where I had lined up the teeth on a very narrow jaw that looked beautiful, but all the teeth were tipped off their base. Orthodontics as it was practiced prior to Tweed was in very bad shape. Many of us thought we might have to give it up.

DR. WAHL You had annual national and regional meetings of the AAO, as we do today. But with no continuing education requirements, there were very few short courses to choose from. What did you do to keep abreast of the latest developments?

DR. MUCHNIC All the members of the Southern Section of the Pacific Coast Society of Orthodontists, from Bakersfield to San Diego and from Santa Monica to San Bernardino, could hold their meetings in a room the size of my study. There were about 20 of us. We'd meet three or four times a year, just like we do now. But we'd go to each other's offices--everybody was downtown then--and see what the others were doing. They weren't very happy with their training, either.

In those days papers were always discussed--rather heatedly at times--and from these discussions we learned a lot. Now papers are rarely discussed, which is too bad both for the essayist and the audience. In the older journals many of these discussions were printed following the articles. I know of one instance where a heated discussion caused an essayist to refuse to publish another paper. That was Dr. Crozat--a great loss to the profession.

DR. SIDLOW It wasn't at all uncommon for someone to send his followers to a rival's lecture simply so they could boo!

DR. MUCHNIC There was another group of orthodontists, the Angle Society, who wouldn't associate with our PCSO group at all. Dr. Angle had no use for the AAO, although he just about started it around 1900. And as far as Angle was concerned, his was the only society. He really put the fear of God into them. There was no room for deviation. It's my personal feeling that they were so unsure of themselves that they dared not deviate, for fear of what might happen. Dr. Angle was a brilliant man, but he was also a very dogmatic man. The story goes that he'd wander into one of his disciples' offices and open one of the drawers, and if he found an instrument that didn't belong there, the man was out! A PCSO member could not publish in The Angle Orthodontist, as I recall, and vice versa, although there were probably a few exceptions in the East. But after Angle died, there were fewer and fewer of his graduates left, while the AAO continued to grow.

DR. WAHL Did you have study clubs?

DR. MUCHNIC Yes. Atkinson organized us into two study groups around 1933-34. We'd go out to dinner and then meet at his home in Altadena. There were only six or seven of us. He'd lecture to us about all phases of orthodontics, although he might start out on one subject and finish on another. He was a very fine photographer as well (Fig. 2).

DR. SIDLOW In the late '30s it was very chic to go to Europe and take a course. I was in Vienna the day (Prime Minister Engelbert) Dolfuss was shot. I was there to study under Albin Oppenheim--the one who did some studies on cementum that were not very favorable to orthodontics. He developed a rubber dam to make elastics, because he contended that the heavy forces were damaging the cementum.

DR. MUCHNIC Spencer Atkinson was from a very prominent Southern family who had some clout with the State Department. He discovered that Oppenheim was in trouble--because he was part-Jewish, he was on the Nazis' "hit list". Atkinson saw to it that Oppenheim got out with all his furniture, all his models--the whole works. He left for America the day before they came to arrest him, and he would say later that there was at least some satisfaction to hear that they had sent a limousine for him.

DR. SIDLOW There was another man in Vienna by the name of (Bernhard) Gottlieb. He and Oppenheim were enemies. I kept in touch with Gottlieb and, along about 1940-41, was influential in getting him a job teaching oral pathology at the University of Michigan. We knew he wasn't getting much money, so we organized little courses, where eight to 10 of us would chip in about $25 so he could take back with him $200 to $300.

DR. FARBER When I came to California, I met two people who influenced my way of practicing. One was Herb Muchnic, and the other was Gene (I. Eugene) Gould. Gene introduced me to Oppenheim, who impressed me as not only a wonderful person, but as one with a whole new attack. He taught me extraoral anchorage.

I used to go to Gene's office about once a week. He was using a great many removable appliances. He used what is now described as a Schwarz plate--split uppers, split lowers--and headgear. He had been a classical Angle man who moved away under Oppenheim's influence. I learned from Herb, too. He was very friendly and very supportive when I came to town--which you don't find much any more.

DR. MUCHNIC I was influenced by Hays Nance, who was trained by Albert Ketcham, another Angle graduate. We used to visit each other's offices. You know how we used to display our models in those glass cases? I'd go to Nance's office in Pasadena and look at his cases, and they were just gorgeous!

DR. WAHL By the time of Angle's death in 1930, it was considered sacrilege to extract teeth. Yet the concept of extracting to create space had been quite prevalent in the late 19th century. As late as 1892, Angle himself had believed extractions were justifiable.10 In the mid-'20s some of Angle's own followers--including Frank Casto, Martin Dewey, Lloyd Lourie, and Albert Ketcham--broke away and were branded as "Angle-Worms" and "Angle-Phobes". Ketcham apparently received hundreds of unsigned postcards, each bearing only the picture of a jackass. At any rate, the nonextraction pendulum had reached its apogee by the mid-'30s.

DR. MUCHNIC The influence of Angle was so strong--I had a case where all four cuspids were blocked out. I sent the patient back to her dentist suggesting that he take out her four first bicuspids. The dentist brought me up before the dental society! Fortunately, there were enough of our group who explained it was such an obvious case that it just had to be done.

DR. SIDLOW There was a man in Massachusetts who wrote an article where he said that orthodontics was easy. He advocated taking out first bicuspids to make room. Well, they wanted to crucify him! Because, according to Angle, you never compromised the arch. The other thing was that we had no mechanism to parallel roots. All you could do was tip.

DR. MUCHNIC So what happened was that you started to produce double protrusions. What else could you do when you had a crowded arch? Of course, there were times when all the teeth were in but the upper cuspids were blocked out, and they would wink at it. They never admitted it, but they extracted. You couldn't expand it that much.

DR. WAHL When did you finally break away from the nonextraction camp?

DR. MUCHNIC Around 1940 another Angle graduate, Charlie Tweed, appeared on the scene. He was a man of great courage. He realized he wasn't getting anywhere with some of his cases unless he extracted. And we realized that we were having a tough time expanding teeth in order to avoid extraction. At one PCSO meeting, he chartered a couple of Pullman cars and brought to Los Angeles a whole flock of patients, in all stages of treatment, so we could examine them. That was when Angle's hold started to break.

DR. WAHL All of us have known dentists who withhold referral of youngsters until full eruption. It would seem that the orthodontic profession is responsible for a good part of that attitude. In the '30s, did you do what we now call "first-phase" treatment?

DR. GAWLEY Oh, yes. To me there's nothing quite so stupid as leaving a child with a crossed lateral incisor, rather than getting some of the deciduous teeth out of the way to make room for that incisor to cross over. I put on a clinic some years ago where I showed what could be done if a child is missing, say, the lower second bicuspids. If the arch was crowded, you could take out the primary second molars, put bands on the six-year molars and lateral incisors, and draw the deciduous first molars back. And the deciduous molars would take the first bicuspids with them.

DR. WAHL Did you use headcaps in early treatment?

DR. GAWLEY Yes, but as you know, it's got to be consistent for it to work. For many years I've advocated the use of a high labial, as a lip bumper, along with the headgear. They have to wear either one or the other. Another invention of mine was a unilateral, swivel-type facebow. Another idea, for ectopically erupted molars, was a brass separator wire soldered at its tip to a thin (.012" or .014") ligature wire used as a threader. Of course, you have to make sure there are no bumps when you solder it.

DR. FARBER I was originally trained as a children's dentist. The Johnson appliance lent itself very nicely to that, since it was essentially a 2 x 4 appliance. That, plus a headcap and a lingual arch, gave you an armamentarium which was almost equivalent to what you use today.

DR. MUCHNIC The McCoys (Drs. James D. and John R.) had an axiom that you treated a malocclusion when it first appeared, no matter how early. I didn't follow it that closely, but I did treat in the mixed dentition.

When Oppenheim came to USC, he showed us what he was doing with headgear. He had been treating some of the royal heads of Europe, including the Hapsburgs, with headgears! His was an .045" labial wire that had a prong at the midline, attached to a kind of handlebar. This, in turn, was connected by elastics to a hairnet, similar to that used at one time by Angle. Unitek made a complete assembly in the late '40s, except that we had hooks sewn to the hairnets. But it was almost impossible to get the boys to wear them. I tried them on my own kids. Half the time we'd find them on the floor in the morning. It was only when Sy Kloehn came out with the neckstrap in the early '50s that headgears began to take off.

DR. WAHL The edgewise mechanism had been commercially available since the late 1920s, but it still hadn't surpassed the fixed appliances of the time--such as the McCoy open tube, the Atkinson universal appliance, and the Johnson twin arch--in popularity by the early '30s. Even Angle's ribbon arch, introduced in 1916 and the predecessor to the edgewise mechanism, was still being used. Minor tooth movement was achieved with the Oliver upper labial arch and Mershon lower lingual arch; this was called the labiolingual appliance when they were used in combination.

While bodily control of teeth was possible with most of these fixed appliances--in skilled hands--they were all developed with expansion and subsequent tipping in mind. It is ironic that the edgewise system derived from Angle, the man who spoke most vehemently against extraction, became extraction's most popular vehicle.

DR. MUCHNIC In the early '30s, the Krupp people in Germany came out with a new material, stainless steel, which they thought might be useful in dentistry. I, who was using the McCoy open tube, and others who were using the Mershon arch began to see that you could use a much lighter wire with stainless steel. The McCoy technique used an .025" gold wire, and labiolingual wires were typically .036" to .040".

These things came together, and Atkinson developed a bracket similar to the ribbon arch bracket, in stainless steel, with a vertical slot where the ribbon arch would go in, and another slot to the gingival to receive a second wire. These were pinned in exactly like you pinned in the ribbon arch. It was the first fullbanded appliance that I used. Of course, the McCoy appliance used bands, but you usually banded only the four anteriors and the molars, sometimes the first bicuspids. And then with finger springs, you could get the other teeth into place.

DR. WAHL Until mid-century there was no such thing as a preformed band. A strip of metal, carrying the appropriate bracket, was closely adapted around each tooth, pinched against the lingual surface, and then flame-soldered. Tiny eyelets were often soldered to the labial surface of the band for rotational control. Some practitioners preferred to fit the molar bands "indirectly" on stone or amalgam dies, and molar attachments were also soldered on individually.

Where did you get your bands and wires before there was a Rocky Mountain or a Unitek?

DR. SIDLOW Precious metals we'd buy from houses like Aderer. All our wires were gold. Band material was platinum. In the mid-'30s, Rocky Mountain came out with steel banding material, which you could adapt better because it was thinner-gauge than the gold. I welded the attachments myself for a long time, but after World War II, I called the Veterans Administration and said, "You know, the war produced some very good dental assistants. Why don't we try to get some of the fellows into our offices? A dental assistant doesn't have to be a woman." The man they sent became the first one in a new program. We had a pay scale based on $30 a week, which was pretty princely for those days. He later studied dentistry and eventually became dean of the University of Detroit Dental School.

DR. MUCHNIC S.S. White supplied you with most everything you needed in the way of edgewise and ribbon arch. And many of the orthodontists were innovative. The fellows themselves came up with all kinds of things. I gave a paper once where I tried to show that stainless steel could be used in the mouth. But the McCoys and others were very leery of it, persisting in calling it "iron". They said, "You watch and see, you'll begin to get rust marks on it."

DR. FARBER It was the late '40s before I saw any preformed bands. And they weren't preformed very much; they were more or less cylindrical. They did have a little indentation for the buccal or lingual groove, but they were not contoured. I remember when the people from Unitek began to ask what we'd like in a band, things began to change.

Rocky Mountain was the first orthodontic supply house. They brought out the first welder in the early '30s. Before that, our supplies were garnered by a salesman. He would scrounge up pliers from optical houses and from a wide variety of other sources. In order to get a welder other than Rocky Mountain's when I first came to California, I had to buy a set of universal brackets from a guy named Ret Alter, who was the forerunner of Unitek. It was an improvement over the early RM welder, and I still have the brackets!

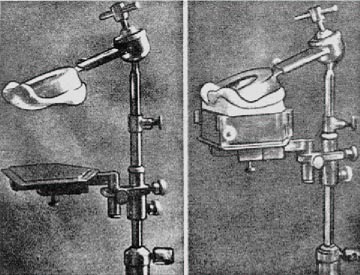

DR. WAHL Dr. Muchnic mentioned the McCoy brothers earlier. Their office, built in 1926 five miles away from downtown Los Angeles, was the envy of their colleagues.12 It occupied the entire third floor (more than 2,700 square feet) of a building owned by the brothers. Its richly decorated interiors blended with the building's Spanish Colonial Revival architecture, and it featured such amenities as an outdoor patio, a staff kitchenette, an x-ray/photography room, a lab, an intercom system, and foot-operated faucets. It was designed for smooth patient flow, with two operatories per doctor and an open secretary's station that commanded a view of both the reception room and the operatories. The McCoys estimated the cost of equipping their entire 14 rooms at less than $12,000--an amount barely enough to cover the cost of today's panoramic unit. I assume your first offices were not so opulent (Fig. 3).

DR. FARBER I started with a one-chair office, rented for I think $70 a month. I had a chair, a cuspidor, and a cabinet, with a second chair set up for x-ray and photography. I stood at the chair.

DR. MUCHNIC I stood at the chair till after the war. I wrecked my knee temporarily, so I had to learn to sit down. I had to rig up a new set of drawers because my Angle table was no longer suitable.

DR. GAWLEY That's why I'm having trouble with my knee. Stood all my life.

DR. SIDLOW In 1924-25, I was taught this stance, leaning over the patient, and it left me with my left arm longer than my right. I know this when I put on my shirt. Then in the '40s they introduced the stool. It had a swivel on the bottom so you could bend any way. Then you had to tip the dental chair back, and you were always afraid the patient would swallow a band.

DR. WAHL "Satellite offices" were unheard of in the '30s, but only because the name hadn't been invented. Were there any other options for branching out, other than teaching and research--such as going in with a dental group?

DR. MUCHNIC There weren't any dental groups. Even the advertisers didn't want to bother with orthodontia. There were no clinics, except of course at the school.

DR. FARBER When I came back after the war, there were two clinics. One had started in conjunction with the school system, but had broken away from it. The other was in southwest L.A., which split off into the San Fernando Valley. In the early '50s, the longshoremen set up a clinic in San Pedro. They hired some very fine orthodontists.

DR. WAHL I'd like to get an idea of just what practice was like in the '30s. For instance, how did you take impressions?

DR. SIDLOW Originally, I used compound. That wasn't satisfactory, because if there was an undercut someplace, the material dragged. Then we used Dentacol, which was plastic and came in a tube. You had to take it out of the tube and load it into a syringe. It had to be heated before it would flow. You emptied it into a metal tray that was lined with little pipes, through which cold water would flow, to chill it. Sometimes, I must confess, you got it a little too hot, and the kid screamed.

DR. GAWLEY We used a material that we made ourselves. I can't remember the formula exactly, but it had seaweed in it. We made it up first thing in the morning and heated it in a double boiler, so we had it ready any time we wanted to use it. And once you used it, it had to be thrown away. Of course, you used compound for lingual impressions.

DR. MUCHNIC We started out with plaster impressions. That was a mess!

DR. SIDLOW After the set--which generated no small amount of heat--you'd pry off the tray, leaving the plaster on the teeth. Then you'd take a sharp knife and make an incision between, say, the central and the lateral, in the case of an upper. Then you'd go over a tooth or two and make another incision. And by the time you incised those places, you could stick your knife in the groove and by twisting a little, a piece would come off. You'd take all the pieces, wash them with a brush, and put them together. Then you'd apply two coats of shellac, one coat of sandarac, and a coat of oil, and pour it up.

DR. WAHL What was life like without a model trimmer?

DR. SIDLOW We had a big, long file with coarse teeth, and you just filed and filed.

DR. MUCHNIC The problems were enormous. We were using a plane, a saw--you spent such an inordinate amount of time doing it. Some of the guys were lucky in getting some kind of lab man who developed a certain amount of skill at it.

DR. GAWLEY Do you know what gnathostatics is? It's what we used at USC to trim models. We had an instrument that was used while the impression was still in the mouth. Then we trimmed the model parallel to the Frankfort plane. We've used it in the office ever since.

DR. MUCHNIC There was also a little device where you put your canine plane. Then you poured your plaster into a model former to make the base (Fig. 4). All your bases looked alike--they were kind of pentagonal in shape. The occlusal plane usually went up very steeply because the top of the model was parallel to Frankfort. And it was hard sometimes to set your models on top of one another.

DR. WAHL Did you get the intraoral x-rays from the dentist's office?

DR. GAWLEY Generally we did, but if you could, you got them from McCormack. We took our own photographs, and got them gnathostatically also. We didn't take intraoral photos.

DR. MUCHNIC I began taking dental photographs very early with Kodachrome slides. I had a photographer friend who set me up with extension lenses and an Argus 35mm camera.

DR. WAHL When did you start taking cephs and analyzing them?

DR. SIDLOW I started taking them about 1935. In 1940 Herb Margolis came out with positioning the lower anteriors at right angles to the base of the jaw. It began slowly--this guy added something, that guy interpolated something--and so it grew. Then it helped you determine whether or not you'd extract.

DR. MUCHNIC I had an associate in the late '40s, Phil Klein, who was a classmate of Ricketts and Pruzansky at Illinois and taught me a lot about cephalometrics. I took him down to the school and asked Spence Atkinson if he could get a cephalometer and let Phil teach it. You see, Spence and Holly Broadbent were classmates at the Angle school. "Well," he said, "I'll do it if Holly will come out and show us how to use it." Somehow we got the $4,000 together and had one shipped out. Then another orthodontist, Del McCauley, and I got a machinist to make a head holder for it. And Phil sat us down and taught us how to make tracings.

DR. WAHL I guess the problem of appointment control has been with us ever since Pierre Fauchard told his first patient to come back in four weeks. What kind of staff help did you have in the '30s?

DR. MUCHNIC In those days, the average orthodontist had two chairs and one assistant, and did just about everything himself. The assistant acted as receptionist as well as chairside. Later on, he added another assistant. I once had an assistant who was terrific with her hands. I took care of the books, and I let her do all the extra soldering, pouring up models, everything but putting the bands on. In those days, we didn't use assistants like we do now. They didn't do anything at all in the mouth.

DR. SIDLOW I had an assistant who was both bookkeeper and assistant. I paid her $10 a week. I later graduated to having a dental hygienist plus a girl at the desk. At the maximum, I had four girls.

DR. GAWLEY We generally had a chairside assistant. When we weren't too busy, she worked in the lab, pouring models and that sort of thing. Then we had a girl that worked at the desk. When we got busier, we had a girl in the desk, one in the lab, and one at the chair.

DR. WAHL What were the uniforms?

DR. GAWLEY They wore a regular nurse's uniform. I wore a smock over a shirt and tie.

DR. FARBER In my New York office, we wore a gray office coat, like a clerk's jacket. We didn't want to look too "institutional". On the other hand, when I came to California in 1942, I switched to wearing long whites and a short-sleeve white shirt, with white shoes. After the war, I wore a blue coat. Now I don't wear any kind of uniform. My assistant wore a regular nurse's uniform, with no cap--although they wore caps in some of the offices. They wore white in my office until about 15 years ago.

DR. WAHL What about fees? Was orthodontics considered a "rich man's treatment"?

DR. MUCHNIC No. I learned that during the Depression. I found that people in relatively modest circumstances, even those who were having a hard time, would be perfectly willing to pay the fee if they could pay it out over a long period of time, because they wanted to do things for their kids. There was no insurance at that time.

DR. SIDLOW In 1932-33, I got $50 for the appliance, then $10 a month as long as it would take, depending on patient cooperation. That included records and retainers. So if the case ran two years, it would be about $300.

DR. MUCHNIC When I started with Dr. Friedman in 1929, he was charging $500 a case, which was a pretty good fee. But fees went down with the Depression. Some of the fellows had it pretty rough, although I managed to keep pretty close to $500. It was a matter of how much a month you got. Usually, at that time, they could pay about $10 a month.

DR. FARBER In our "morning" practice, I think the initial fee was $100. The monthly fee was $15, with a two-year average. It was an open-end fee. When I got into that office, I inherited dozens of Dewey's cases that were never finished. He didn't believe in retaining. He just believed in keeping treatment going. He was a very bright, chaotic man.

DR. WAHL How many patients could you see in a day?

DR. SIDLOW About 20. You see, with the lingual appliance, you would typically release the locking wire at the half-round post, remove the lingual arch, and let the patient either rinse with Lavoris or brush. In the meantime, you'd go into the laboratory and pumice the appliance. Unless, of course, a band had to be recemented, which happened very often, with the consequent decalcification.

DR. FARBER We used to see patients weekly. You could see quite a few, because when you were treating with a labial arch, you would normally just retie or replace a ligature. So you could see a patient in five minutes.

DR. WAHL If you got poor cooperation, did you charge extra?

DR. MUCHNIC I did. A lot of them didn't. I hated a flat fee for that reason. There was a time in the '60s when I really had problems with kids, especially college kids. That was the time of the Vietnam War.

DR. FARBER I ask more from the kids nowadays than I used to.

DR. WAHL Dr. Gawley, did you ever have an uncooperative patient?

DR. GAWLEY Don't ask me that! Some of them you wish to God you'd never seen. But then the rewards make it all worthwhile. Like the times in church when a woman comes up to you and says, "Oh, Dr. Gawley, you straightened my teeth 40 years ago." I also straightened the teeth of two Rose Queens--'39 and '45. It made me very proud.

DR. SIDLOW I had a sign in the office that said, "DON'T BRUSH YOUR TEETH". The child would look at the sign and say, "Look, Mom, Dr. Sidlow said don't brush your teeth", but in smaller print underneath it said, "BRUSH YOUR GUMS". I knew that if I just told the kids to brush their gums, they'd never do it. The Butler people liked the idea so much that they made up little cards with that sign on them.

DR. WAHL Dr. Muchnic, as a way of summing up, could you comment on how you think the profession has improved in the ensuing years, and how it has deteriorated?

DR. MUCHNIC Physically, it's improved tremendously. Of course, you've got bonding now. There are so many things that you've got available. I'm still amazed when I go to meetings, even though I'm not practicing, to see how easy it is to do things. I wish I could get back in.

On the other hand, you have the problem of professional liability insurance going so high, and the threat of suit, which you rarely heard of in years gone by. And then there's the commercialization. I know some very good orthodontists who've given up and gone to work for these groups, and I can understand it. A lot of dentists have a really hard time with the mechanics of running an office: the hiring of personnel and keeping them, the rental situation, the space situation, the equipment. This has become more and more complex as time goes on.

DR. WAHL Do you think orthodontic meetings are putting too much emphasis on promotion, productivity, and management?

DR. MUCHNIC The meetings are putting the emphasis on the things the orthodontists want to hear. Nobody is pushing it down their throats. There are a lot of orthodontists who are not doing what they expected to do financially. They want bigger practices. They want to work faster. They want to work on more patients at a time.

Our generation was lucky. We had a lot of bad things happen--the Depression, the war, the dislocation. But to balance that off, we came back to a population explosion, a baby boom. You could work as hard as you wanted. There was no limit to what you could do.

DR. WAHL You gentlemen flourished during a decade that opened with a crash and closed with a bang. I'd like to thank you for teaching me something about the heritage of my profession. Your reflections are a priceless resource, and I hope we have managed to capture a fragment of them in print.