JCO Interviews Dr. Charles J. Burstone on the Uses of the Computer in Orthodontic Practice, Part 1

JCO What is the future of computers in orthodontics?

DR. BURSTONE Within five to ten years, I expect that you are going to see computers in most orthodontic offices (Fig. 1).JCO How much are orthodontists going to have to learn about computers?

DR. BURSTONE The average orthodontist may not have to know very much about computers, just as he might drive a car and not know anything about how it works.JCO Do you think that the individual orthodontic office will have a computer terminal with a case analysis program in it?

DR. BURSTONE Yes. Our interest here has been primarily the development of programs which will help the orthodontist from the point of view of case analysis, treatment planning, and treatment. Of course, the use of computers relates to the business aspects of practice as well. So, I think that orthodontists will need a small computer in their offices for business, scientific and clinical purposes. Combining these usages provides a most valuable office tool, and that is most certainly the direction in which we are going.JCO You use the computer for these purposes here at the Health Center clinic?

DR. BURSTONE Our patient scheduling is all done by computer. We record clinical exams, recall our patients, find patients who are suitable for treatment by students. We get monthly printouts on the status of all our patients, including what stage of treatment they are in and how long they have been under treatment. I think that our treatment time here may be a little shorter than average and one reason for it is that we monitor it so closely. It cannot be monitored as easily by hand.The computer stores and retrieves information about patients under treatment in this facility. Every patient has a treatment card. After the doctor has seen the patient, the procedure is entered by code number, and the amount of time spent. We want to know how long each procedure takes and how long it takes to treat a case. Information can also be typed directly into the computer at the terminal.

If we want to look up something about a patient, we have a "Look Up" routine. By putting in the correct identification number--and the terminal will tell us if we are putting in an incorrect number--we can retrieve a patient's identification frame. The information normally on a patient history card is flashed on the screen--name, address, phone number, parent's name, and other information. We can retrieve his financial frame, admission date, treatment history. The treatment information frame tells us the date of the last visit, what was done, who the student was, who his

preceptor is.

If we want to know what patients are going to be in the clinic next Thursday, we retrieve the scheduling data for that date. If there are more than fit on one frame, it is advanced until you see all the patients scheduled for that day.

JCO What can the computer do in the individual orthodontist's office?

DR. BURSTONE In the past, many orthodontists felt it wasn't practical to do a complete cephalometric examination. They felt limited by the demands of their office to only a few measurements. I think now it is possible to make many measurements and do a thorough analysis for your patient. It is important in the average orthodontic case, but particularly important where you are planning an orthopedic change or any type of orthognathic surgery. There is a special surgical-orthodontic cephalometric analysis, which we published in the Journal of Oral Surgery.This is one type of data base. Minis can also be used to recall information from your clinical exams and records. In addition to the usual information about patient control, an orthodontist might be interested in information such as the number of cases he started versus the number he finished. The things that you have written about as indices to look for in a practice are the kind of things that computers do easily. They can be done by hand, but computers make the information automatically and easily available to the busy clinician. The computer can draw graphs, such as you have published in JCO, of how the practice is doing in various regards.JCO Are orthodontists perhaps too individualistic to accept a prepared program ?

DR. BURSTONE I think there will be a number of very good programs and the orthodontist will select the program he likes. It is inconceivable that every orthodontist will want to program his own material, unless it was his hobby. If there were resistance to good, suitable programs, perhaps the orthodontist would have to be educated to what a good program is. A good program must be flexible, taking into consideration individual variation in both the business and professional components of the office.JCO Which diagnostic records do you use for treatment planning?

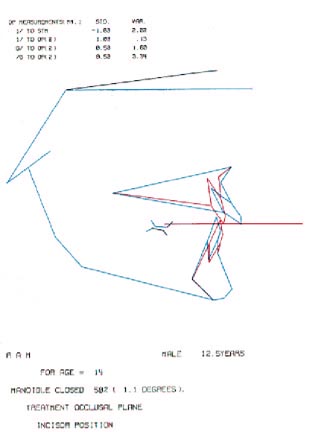

DR. BURSTONE Since the early '50s, I've worked with two records--a lateral treatment plan tracing (Fig. 2) on which we fix facial profile and where the teeth are to be moved, and an occlusogram. I developed the occlusogram for treatment planning, because I consider it to be a valuable record, since a good part of our decision making is in the occlusal plane. I think it is necessary to bring in the third dimension for computer treatment planning. The occlusogram is a tracing of the occlusal of the study cast from a 1:1 photograph.All the important treatment decisions can be made from these two views. To do many lateral tracings and occlusograms manually is very time consuming. The computer does them accurately and rapidly. It doesn't do any more than you could do by hand, but it makes very detailed workups feasible for the first time. This means better treatment plans and, hence, better mechanics, since we know where we are going in treatment.

JCO How do you use the equipment for cephalometric analysis?

DR. BURSTONE We have a digitizer that interfaces with the computer. We digitize headfilm tracings (Fig. 3). We could digitize the headfilm itself, but we feel it is more accurate to make a tracing and to number the various landmarks. An assistant may not see the landmarks on the film so well. Also, the tracing gives the orthodontist a chance to check it if he wants to. Since the points have to be digitized in sequence, it may help to actually number the points on the tracing in the beginning. As each point is digitized, a beep lets you know that it recorded. We have 52 landmarks which include all the points in our cephalometric analyses. The computer draws the tracing on the screen as a check for digitizing errors. If the diagram on the screen doesn't look like the tracing, you can redo the digitizing.The unit attached to the computer prints out a hard copy of the cephalometric analysis as a permanent record. The printout gives a mean by age or sex and the individual's variation from it in millimeters or degrees of deviation.

JCO Let's talk about the data base in your computer program. Where did your normals come from?

DR. BURSTONE We traced and measured headfilms from the Denver Child Growth Center, where an excellent longitudinal sample had been collected. We look askanse at samples that are not longitudinal, which use cross-sectional material or, even worse, patients from orthodontic offices. You end up with a mixture that probably won't describe the population you are interested in. This is particularly important if growth data is to be individualized for the patient. We have standards for age and sex from 5 years to 21 years. In addition, growth increments have been established using facial age, which is a developmental age rather than a chronological age.JCO What about race?

DR. BURSTONE This sample is from Colorado and is not applicable, for example, to a Puerto Rican population. But the way I look at cephalometrics is that it describes what you have and is not a treatment plan. For descriptive purposes, this sample is useful, until we get more specialized data for race.JCO How does your analysis compare to others?

DR. BURSTONE The means were pretty close to Downs and other similar analyses.JCO Many clinical orthodontists question the validity of the concept of normals and treating your patient to a set of cephalometric standards. The orthodontist says, "I am treating this individual. I am not treating him by the numbers."

DR. BURSTONE I would agree that the reason you do cephalometrics is to get a better understanding of the orthodontic case you are going to treat, and not to develop a treatment plan. I look at the head film very much as a general looks at his maps before he plans a battle. He wants to know the terrain he is dealing with. I think that the reason we do cephalometrics is to find out the variation inherent in the individual, by comparison to a standard. The treatment planning is separate. It is a misuse of cephalometrics to use any of those numbers as a goal for treatment planning. For some years, it was common for orthodontists to treat by the numbers. I hope that most orthodontists have gotten away from that idea and that they use cephalometrics for its legitimatefunction, to let you know the morphology you are dealing with and to describe how the patient differs from the standards.

There are certain measurements that may give us some clues to growth patterns and measurements that let us know how much change we produce with treatment, but in no way are any of these standards to be used as guidelines to treatment. A specific example of this is, as Bjork is suggesting, that there are certain criteria that should be looked at in the shape of the mandible and other parts of the face that would indicate what type of rotation in the mandible you might expect with growth. This is proper use of cephalometrics, looking at variation in the shape of the jaw. Improper use of cephalometrics would be to take some specific number and we could use, as an example, lower incisor to APo as a guide to lower incisor position.

JCO That's one relationship that a great many orthodontists use for a treatment goal.

DR. BURSTONE Lower incisor on the average is 2mm forward of APo. The interesting point is that the standard deviation is ±2mm from the mean. 99% of the population of good occlusions falls within 3SD. Three times 2mm is 6mm on either side of the mean. So, there is about a 12mm range of variation normally for the position of lower incisor to APo in untreated people. Well, most orthodontists are probably not going to vary their incisors more than 12mm, and 12mm is too large a range to give a definitive plan.But, the big fallacy would be to think that the lower incisor always should be 2mm forward of APo. If the mean is +2 and you have a patient who is 8, you can say that the lower incisor is protrusive. But, 8 might be very desirable for that patient. There are a number of patients with adequate lip length and a very large soft tissue chin who are stable and esthetically attractive with protrusive lower incisors. We don't want to fall into the trap of using any of these standards as absolutes.

We could make the same comments about lower incisor to Frankfort, which is a Tweed measurement. It has a standard deviation, depending on age, of about 5 degrees. Three standard deviations is 15 degrees. So, there is a 30-degree variation in the position of lower incisor to Frankfort. Most orthodontists would not go beyond that range anyway.

JCO Even two standard deviations would be quite a range.

DR. BURSTONE Right.JCO Do you not have any bias with .regard to protrusion? Does it offend you if somebody is protrusive in appearance, or do you say, "People can be protrusive and it's not up to me to judge whether they should or shouldn't be"?

DR. BURSTONE Beginning with my graduate thesis back in 1955, I have always said if you want good facial esthetics you have to look at soft tissue. Measurement of teeth and hard tissue will not be predictive of esthetics. Before you start to determine what tooth movement you need for the kind of face you want, you have to have a concept of what type of face you are interested in.JCO What is your concept of good facial harmony and beauty?

DR. BURSTONE In Indianapolis, we collected a sample of adolescent individuals who had goodfaces. I have often found that orthodontists are the poorest judges of good faces. After a while you see your treated results and you think that type of face looks good. So, we had an independent group of artists and housewives look at photographs of children to identify the faces they thought were the best. It was very interesting, because all of the judges agreed on what the good faces were. They categorized faces on a scale of 1 to 5, and we selected 1 and 2 for our cephalometric studies to see if there were any soft tissue measurements that would give us good facial form. We took headfilms, and we measured hard tissue as well as soft. We found a great deal of variation in the amount of lip protrusion and facial convexity in faces that were considered good looking. There was also a great deal of variation in any of the typical cephalometric measurements--lower Incisor to APo, lower incisor to Frankfort--in untreated people that have good faces. So, if you want good faces, you don't treat to any dentoskeletal mean.

JCO What do you do?

DR. BURSTONE Though I don't believe in averages for cephalometrics, I think there is somemerit to using averages in evaluating facial harmony. If you have lips that are protrusive, most people will not consider that to be good looking. If there is only a little bit of variation, you can still have a good face. If you are too many standard deviations away from normal, as you walk down the street everybody knows that you are different. So, means have some value in our society where people want to conform to certain ideas of appearance. If you look at the faces that are used in advertising, they are very close to my soft tissue means.JCO So, a standard for facial esthetics is a soft tissue standard, with little or nothing to do with the hard tissues?

DR. BURSTONE The reason you can't go by hard tissues is that there is a great deal of variation in soft tissue thicknesses, almost more variation than there is in the dental-skeletal pattern. So you cannot just look at teeth and bones. A good part of treatment planning is a consideration of facial form and it should relate to a soft tissue analysis.JCO What factors do you use in your soft tissue analysis?

DR. BURSTONE The components of the soft tissue analysis that we have in our computer include the facial profile, lip protrusion, lip thickness and the function of the lips--how they close and their functional relationship. As far as lip protrusion is concerned, we have a reference line that goes from subnasale to pogonion. We purposely avoid structures like the nose, which is highly variable.JCO Nevertheless, the orthodontist has to make a treatment decision about the location of the anterior teeth and when he does, at least for most orthodontists, facial esthetics is one of the criteria he is thinking about.

DR. BURSTONE Right. It is one. The other criteria are stability and ease of lip closure. Let's see how this might fit together to give us the determination we want. We might have two patients, both with protrusive lips. In one instance, there might be adequate lip length and no difficulty in covering the vertical dimension anteriorly and no problem with arch length inadequacy. We would probably leave that patient in protrusion. Certainly if someone can close over protruded teethwithout a great deal of strain, this can be esthetically desirable. On the other hand, we may have another patient with the same protrusion who may have a large interlabial gap and can't close the lips. That's a different story; reduction of the dental protrusion is needed.

JCO Supposedly, there is a balance among health, function, stability, and esthetics--dental and facial esthetics. Do you have any evidence with regard to stability which would influence you as far as the position of the upper and lower incisors is concerned?

DR. BURSTONE Stability is in the no man's land of orthodontics. There has been research in which the forces of the tongue and lips were measured with strain gauges. But, in the average patient, it appears that if you move lower incisors lingually the tongue will adapt. So, there are minimal limitations on lingual movement of incisors. There are always special cases of tongue thrust where this can't be done, perhaps an abnormal swallowing pattern, or a larger tongue, or a forward positioned tongue. But, typically, it appears that the tongue will adapt to lingual movement of the lower incisor.JCO What about the lips?

DR. BURSTONE If you attempt to move the incisors labially, then we have to determine if we are going to be moving the incisors against the pressure of the lips when the lips are closed. My soft tissue analysis includes guides for looking at lip drape of upper and lower lips with respect to the incisors. For example, if one had adequate lip length in the relaxed lip position and the lower lip is hanging out anterior to the incisors, maybe you could move the lower anteriors forward. On the other hand, if you have an individual with a tight lower lip, you cannot move the lower incisors safely forward, even though this might seem most desirable esthetically. This is commonly seen in patients with large chin buttons. It isn't the chin button that is large. It is the lower incisors and alveolar process that are back. Unless we can eliminate some of the tension of the lower lip, we probably wouldn't have a stable result moving the lower incisors forward. But all of these things are only guides.Strain gauges can measure muscle forces, but no one has been able to find what determines tooth stability. It is more than a summation of forces. At any given time, the summation of the tongue and lip forces will not be necessarily zero.

JCO Of course, the force is not constant.

DR. BURSTONE Yes. There is a time factor. The periodontal ligament responds to the sum of all forces placed on it over a period of time. Headgears, for example, do not have to be worn continuously to produce tooth movement.JCO How about function? There are many schools of thought, but if, for example, an orthodontist believed in anterior guidance, he could apply some principles of function to where he would place the anterior teeth.

DR. BURSTONE There seems to be some agreement in dentistry on certain objectives--the correspondence of centric occlusion and centric relation, vertical dimension and interocclusal space, functional movements related to cuspid rise or mutually protected occlusion. Certainly, one'sconcept of functional occlusion affects the position of the anterior teeth, since occlusal forces as well as tongue-lip forces determine tooth position. Theoretically, greater overbite or incisal guidance should increase the lingual component of force during incision. This could be a factor in treatment planning lower incisor position.

JCO Are we not then saying that if one doesn't really know what esthetics, stability and function are or ought to be and doesn't know how all this relates to health and longevity of the teeth too well, that it is not surprising that some orthodontists say there is nothing to any of it and treat in a freewheeling manner, while others say, "I need specific number guides and normals are as good as any, because people cluster around normal"?

DR. BURSTONE Just because treatment planning is complicated is no reason not to consider the real factors that go into it. If I thought that computers should be used to treat by the numbers, then I would have designed the programs that way. The programs are designed to be interactive, to vary with how an orthodontist would look at a case and to vary from patient to patient. There are a number of different goals that we should establish and then determine how we are going to reach them in treatment. That is what I mean by treatment planning.JCO How do you determine where the incisors are to be positioned?

DR. BURSTONE Rather than determine the position of the teeth first, I'd rather start with a consideration of what kind of a face we want, recognizing that that might be partly a personal judgment. If we establish the type of face for the individual patient, then we can figure the position of the teeth. For example, typically the lower lip protrudes 2mm to the subnasale-pogonion line; upper lip, 3mm. If I want to treat to that, then for that patient I would figure out where the lower incisor would go to get that lip position. That's far different than just treating to a dental-skeletal standard.If we measure lip thickness, particularly if we use the lower lip as a guide, we can then estimate the position of the lower incisor. We can individualize lip position for the patient. If you think the patient would look better with more protrusive lips--instead of 3/2, maybe 4/3 or 5/3--the lower incisor could be moved further forward. We put that together with ease of lip enclosure and what will be stable. If someone has very short lips, that tells us we probably want to get those lower incisors as far back as we can without unduly flattening the face. It has nothing to do with standards. I think that standards have held back the development of orthodontics. They are good for descriptive purposes. They make you aware of things, but they stop the orthodontist from thinking.

JCO Let's say he has positioned the lower incisor, based on his treatment objective for that. What about the effects of treatment? Suppose he were to consider using mechanics which might have an adverse effect, such as the effect that Class II mechanics might have on the rotation of the mandible or the cant of the occlusal plane. Does he plug that expectation into the various treatment options to see its effect on the tooth relationships and on the face?

DR. BURSTONE I'd like to differentiate between the goal and the plan and what the orthodontist is capable of achieving at the end of treatment. We can't have a goal that is impossible to achieve, and the clinician must be aware of limitations, such as an inaccurate growth estimate orunpredictable cooperation.

I object to building into a treatment plan the effects of treatment, many of which may be undesirable. Let's take the example of deep overbite correction. In big ANB discrepancies, you don't want to correct the overbite by hinging the mandible open. If you have built that into your treatment plan, there would be no motivation to improve the quality of your treatment. Your treatment plan should actually reduce the vertical dimension. It might also demonstrate that you need a great deal of intrusion of upper incisors. Therefore, your mechanics should seek to produce that type of tooth movement. If you merely built in the computer what might normally happen in treatment, many of these results are undesirable.

Some have thought it would be nice to take a lot of treated cases and get a computer bank of what happens, but this has very little relevance to the treatment of the individual case. We hope that the quality of orthodontics will improve and what has been done in the past need not be the guide to treating cases in the future. Let's not confuse the goal with what might happen in treatment. Once you see your goal, then your mechanics should be modified for each patient. For example, deep overbite is not going to be corrected in the same way on a rapidly growing patient as on one who is a minimal grower; not in the same way on a patient with a big AB discrepancy in comparison with a more normal skeletal pattern.

JCO So, you don't believe in building the expectations of the tooth movement that your particular treatment will accomplish in trying to evaluate what the finished result is going to look like.

DR. BURSTONE It may be a bad analogy, but if Jascha Heifitz is going to play a concert tonight, he can anticipate that he will have a few false notes in there. But he does not build that into his practicing and planning for the concert. We do have to have clear-cut objectives. On the other hand, if we start building in the usual mistakes and particularly the national average, I think we are whittling away the quality of orthodontics.JCO There are times, for example, in a brachyfacial pattern where you could open the mandibular plane and not have an adverse effect.

DR. BURSTONE Then that should be part of the treatment plan. You purposely want to do this and you would design your mechanics to erupt teeth, possibly by the removal of the curve of Spee. Many patients with small vertical dimensions have strong musculatures and though it might be desirable for facial form to increase the vertical, it might not be stable. So, our goal should be our best estimate of what is possible and stable, based on our understanding of the patient'smusculature. That doesn't mean we will achieve it. We must monitor it.Another way to get at your question is that I could devise a computer program which could be poor treatment, and I could show that I was reaching that objective every time. That isn't what we want. We want the highest possible objectives that are reasonable for the patient. We want to minimize adverse treatment responses and not build them into treatment.

JCO Of course, mandibular plane can be affected by an interplay of growth and treatment.

DR. BURSTONE The decision on rotating the mandible is based upon what might be stable. Many times you can hinge the mandible open and it might be stable. There might be excessiveinterocclusal space, or there may be a great deal of growth yet to come during the period of treatment. So, you may temporarily hinge the mandible open and in time it may recover.

JCO In fact, most of the time the mandible grows in a counterclockwise direction.

DR. BURSTONE Yes. That is the work of Bjork, that most mandibles tend to rotate in a counterclockwise direction. In a short period of time--a couple of years of treatment--this can be relatively small. But, it is so easy to erupt teeth in treatment, that most clinicians will show a great deal of rotation of the mandible in a clockwise direction on patients that have deep overbites or Class II occlusions. Indiscriminate leveling of arches and the use of Class II elastics are associated with this.JCO Do you use a frontal film?

DR. BURSTONE We use a frontal film primarily for determination of symmetry and to evaluate facial width.JCO Don't you find asymmetry is more the rule than symmetry?

DR. BURSTONE Yes, and diagnosis of asymmetry really counts in planning a case. Many of the midline discrepancies are caused by a skeletal asymmetry. Many times this is missed in treatment planning and, if it is missed, these asymmetries can come back to haunt you at the end of treatment.JCO Do you do a separate analysis of the two sides if you have an asymmetry?

DR. BURSTONE That's an interesting point you bring up. All of our analysis is done by quadrants. To be meaningful, it has to be done by quadrants. For example, a 7mm arch length inadequacy may be used by a primary molar that has been lost unilaterally and, hence, represents a quadrant problemonly. If you do your analysis by quadrants, the decision about where you think the midline should be is a very significant one. It will affect the arch length inadequacy by quadrant, and the type of asymmetrical mechanics required.JCO Don't you frequently find that the occlusal plane is tipped, from the anterior view?

DR. BURSTONE To me, one of the important considerations in treatment is the cant of the occlusal plane. From the lateral view, it is necessary to maintain the proper plane by controlling intrusion and extrusion. Now, with regard to the question of the anterior cant, individual teeth may be off the occlusal plane at the beginning of treatment, but it may be satisfactory overall. On the other hand, after treatment has commenced, it is very common to see unusual cants to the occlusal plane from the anterior view. These are produced by side effects from the mechanics used. My graduate students know if they really want to get me excited, all they have to mention is such mechanics as putting Class II elastics on one side and Class III elastics on the other; and anterior crisscross elastics. This treatment produces undesirable cants to the occlusal plane, which are easily recognized as unesthetic, even by the patient.JCO That is an important point you are making here about tipping the occlusal plane with those mechanics.

DR. BURSTONE When you have a skeletal asymmetry, the midlines of the maxilla and mandible don't line up. I call it an apical base midline discrepancy. You have to plan your mechanics accordingly. You could use asymmetric extractions. You could translate on one side and tip on the other, so you vary anchorage loss from side to side. There are many possibilities. You don't want to use unilateral elastics very much. Occlusogram planning lets you solve the problem optimally at the beginning of treatment, so that desirable mechanics can be planned.(TO BE CONTINUED IN NEXT ISSUE)