CASE REPORT

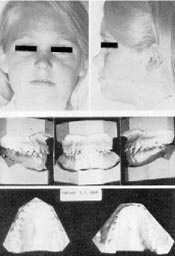

Patient C.M. presented at age 7.5 with an open bite malocclusion (Fig. 1). A thumb habit appliance was worn for approximately six months with successful results, following which the patient was kept under observation for an apparent arch length deficiency problem.

At age 9.8 years, a headplate was taken (Fig. 2) and an RMDS analysis made (Fig. 3). It was decided to await the eruption of the permanent cuspids. Approximately one year later (Fig. 4), the cuspids had erupted in a blocked-out position and the arch length deficiency was measured and confirmed at 9mm. The case had a pleasing facial profile, a normally placed lower incisor, but considerable arch length shortage.

The responsible orthodontist was in a bit of a quandary over what to do and, with the treatment card showing entries such as, "Cuspids blocked out. Ext. ???", he faced the following questions:

1. Could a more forward position of the incisors be accepted? How much arch length could be gained in this way?

2. How much could cuspids, premolars, and molars be expanded and remain stable? Could sufficient arch length be gained in this way to avoid extraction?

3. Would extraction harm the profile in this facial pattern?

Arch Length and Arch Form Analyses

With regard to buccal expansion and arch form, recent research has opened up possibilities for individual case diagnosis, whereas previously many practitioners found themselves either in the "extraction camp" or the "non-extraction, expansion camp".

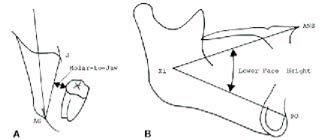

Dr. Randall Schuler has shown that useful norms may be derived for molar expansion. Research on posttreatment cases showed that the position of the lower relative to the frontal denture plane (#'s 19 and 21 on the printout) using the P.A. headfilm, and lower facial height (# 15) in the lateral headfilm are predictors of posttreatment stability (Fig. 5).

In this case, the short lower facial height and adequate space "molar to jaw" indicate the possibility of molar expansion.

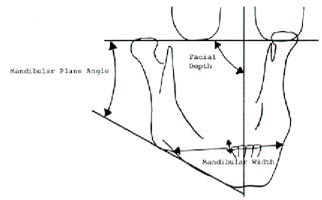

Dr. Peter Lestrel examined arch form in normal occlusions and stable treated cases by measuring the arch width at the contact of the cuspid and first bicuspid. He found arch width to be essentially the same in stable untreated individuals as in stable extraction or non-extraction treated cases. The width of the arch in all three situations was a function of Tooth Size, Facial Depth (#32), Mandibular Plane (#39), and Mandibular Width (#47) (Fig. 6).

A computer equation resulted, which allows a prediction of stable arch width to within ±¾mm as a function of these variables. This equation was then tested on cases where there was expansion at the distal of the cuspids. Those cases showing final dimensions within ±1mm of the computer norm were quite stable, with 90% showing less than 2mm relapse, whereas those either over-or underexpanded showed more posttreatment changes. Therefore, the computer yields:

2( e -bx + ebx )

Based on these three measurements, a two-parameter catenary curve of the form Y= a is calculated through the incisors, distal of the cuspids, and molars (Fig. 7). The computer can use

this curve to calculate space available in the mandibular arch in advance.

The Treatment Alternatives printout (Fig. 3) shows that 5mm of arch length could be gained by buccal expansion, and therefore buccal expansion to the ideal arch form, plus 2mm of incisor labial movement would suffice to remove the 9mm of arch length shortage.

The RMDS analysis (Fig. 3) shows that the facial pattern is best described as "prognathic brachyfacial". Facial depth (#32), a measure of prognathism, is nearly two clinical deviations high, considering the patient's age of 7.8. Lower facial height (#15), mandibular plane to FH (#39) and mandibular arc (#50) all show significant deviations from the norm. Therefore, in the RMDS Treatment Alternatives printout, the facial pattern is "1.7 clinical deviations brachyfacial".

This interpretation plays an important role in lower incisor placement and arch form. Whereas the ideal lower incisor position is at +1 to APo, the "cephalometric limit" is the most labial position of the lower incisor considered acceptable by the computer logic. This limit is programmed more labial in brachyfacial patterns and more lingual in dolichofacial patterns, since--

Therefore, extraction in these cases is a last resort.

Treatment of the Case

A nonextraction approach was used. Retention records were taken at age 14 (Fig. 8). A lower 4-4 fixed retainer was employed. Occlusal tracings of the beginning and retention lower arches (Fig. 9) shows that lower incisors were advanced approximately 2mm, with the remainder of the necessary space coming from buccal expansion. The molars were expanded approximately 2mm, the cuspids were expanded 2mm, and the first and second bicuspids were expanded more than 4mm.

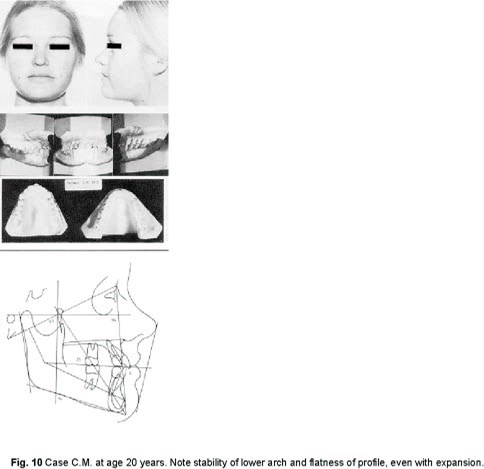

The patient returned seven years after treatment (Fig. 10). The models show a beautiful lower arch, labial and buccal expansion having held. The 4-4 retainer, which was still being worn, was removed at this time. (The patient has since returned to the office six years later with no sign of relapse.)

After seeing the patient's profile at age 20, the orthodontist is very happy that he did not choose to extract in this face.

Conclusion

The result was not an isolated occurrence, but was predictable by computer methods. An occlusal view of the final lower arch was prepared by technicians, using the computer arch form.

There was close correlation between the computer arch form and the actual arch form at retention (Fig. 11). A comparison between the computer "Post-treatment Forecast" and the post-retention tracing at age 20 (Fig. 12) shows striking agreement between the predicted and actual in terms of skeletal, dental, and soft tissue relations.