JCO Interviews Dr. Robert M. Ricketts on Early Treatment, Part 1

DR. BRANDT What should the term "early treatment" mean to practicing orthodontists?

DR. RICKETTS Well, Sid, first let me thank you for the opportunity to talk to your readers again and especially to discuss early treatment. My decision and experience go back to research in cleft palate in the 1940s, and I have practiced earlier starting ever since then. Labels that have been given to different phases of treatment have become somewhat confused. I have, therefore, for teaching and organizational purposes divided the subject into four phases. The first phase of treatment I call "preventive". You can't prevent orthodontics by doing orthodontics, but there are procedures that will mitigate the severity of the malocclusion or even prevent it from occurring in the permanent dentition later. Thus, the first approach to "early treatment" is in the deciduous or primary dentition, or even earlier.

The second phase is in the mixed dentition, and orthodontists often call this "interceptive". The interceptive label applies because the clinician is intercepting the development or eruption of the teeth during the transition from the mixed to the permanent dentition.

The last two categories are not "early". The third phase is "corrective" in terms of having available the permanent teeth to manipulate. This is a popular course to follow for those using multibanded or tooth-bearing appliances. Some orthodontists like to wait until the 12-year molars are erupted to start treatment. When this is the situation, the initiation of the corrective phase may be detained up to 15 or 16 years of age because patients often experience delayed eruption of the upper second molars and very late development of the upper thirds. If correction is the only choice of treatment, the clinician will not start in the young patient. The result is treating of a patient who is not growing or has very little growth left, particularly if the subject is female. Also, orthopedics is progressively limited.

The last stage I call "rehabilitative" because it applies to the adult. Rehabilitating a case with no growth or little potential of physiologic change falls, therefore, under adult orthodontics. Adults take a much different approach.

DR. BRANDT Would you consider the chronological age decisive, or do you measure dental age based on the eruptive levels of teeth?

DR. RICKETTS I try to use all my wits, but I must confess that through the years simple chronologic age has served pretty well for the majority of patients. I recall in my training under Dr. Tom Spiedel at Indiana University in 1943 that he showed records of a patient who had deciduous dentition in one quadrant and a fully developed permanent occlusion in another quadrant. When this can be discovered in the same mouth, how can you "age" a patient from the teeth? I go by chronological age as the first fundamental. Now, if a plus or minus six months is used with chronological age, you will cover about 70 percent of the population. This means that only 30 percent remains, with 15 percent having earlier development and 15 percent late maturing, or about one in six or seven patients.

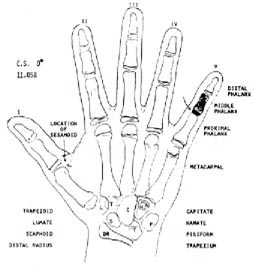

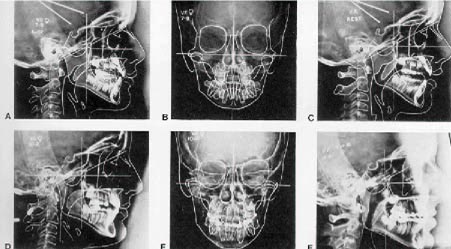

Wrist plates are used for the study of sesamoids, and the epiphysial plates on the second unit of the little finger are observed (Fig. 1). This increases the prediction of a pubertal spurt to ±6 months in about 90% of the cases (according to Dr. Darryl Bowden). Therefore, chronology is first, wrist plates for biologic age second, and tooth eruption becomes a mechanical consideration.

DR. BRANDT In a mixed dentition with crowding it takes longer for the permanent dentition to break through into the oral cavity. Should we classify this as a delayed dentition?

DR. RICKETTS First of all, I'm not sure that it takes significantly longer for a crowded permanent dentition to break through when you witness the early shedding of deciduous canines. That premise is correct only if you have patients who are so crowded that they have teeth which are impacted.

DR. BRANDT What I was referring to, for example, is upper laterals that are blocked out because the deciduous cuspids closely approximate the permanent centrals, and the laterals might not erupt for some time.

DR. RICKETTS Eruption is slowed up, but I would not classify that as a delayed dentition. I would just assume that it was having difficulty in erupting a few of the teeth. Someone recently showed me a patient who was 14 and still had the deciduous teeth. I had a patient whom I treated for six or seven years for whom I had to expose every tooth and bring each up into the mouth one at a time. That I would say was a delayed dentition.

DR. BRANDT Now, Rick, let's reexamine in more detail your definition of interceptive orthodontics.

DR. RICKETTS Well, Sid, it is the intercepting of the maldevelopment of the permanent occlusion. It is approached, therefore, particularly in the mixed dentition as space is made for eruption of the permanent teeth or orthopedic alteration of jaw bases is attempted .

DR. BRANDT Is there true interception of a malocclusion, or is early treatment the best procedure we can get? Can we really stop a malocclusion from occurring?

DR. RICKETTS Oh, yes, there is no question about it in many cases, if not the vast majority. Others are too extensive to totally prevent.

DR. BRANDT How old is your youngest patient who is in appliance therapy?

DR. RICKETTS The youngest patient I ever treated was one week of age. In some cleft palate patients a restraining device is used against the premaxilla within the first week of life. There is a question about the wisdom of doing this routinely, and I don't recommend it except in very extreme cases in which inadequate lip tissue is present or you want to wait for growth to give the surgeon a better opportunity with a larger bulk of tissue.

I treated a non-cleft patient in infancy on one occasion. Some friends had adopted a child who had a severe convexity to the profile. It was almost micrognathic. We put a restraining device against the maxilla at the age of one month and were able to reduce somewhat the procumbency of the maxillary arch prior to the eruption of the deciduous teeth. I would call that one an experimental case, but the analysis suggested an alteration of the midface.

DR. BRANDT How old is your youngest patient in the deciduous dentition who has appliances cemented on?

DR. RICKETTS As a rule, I don't try to work with any teeth until the second deciduous molars have erupted. This tooth usually erupts at about age two and one-half, and the roots are fully formed at about age three. But there is another factor which influences the clinician to delay starting patients until age four or five years, and it involves the practical control and clinical management of the very young patient who is quite sensitive. The three-year old is still tugging on mother's apron strings and is still very dependent. It makes sense to wait until four or five unless it is a cleft palate that obviously needs very early help or is a crossbite which doesn't require patient cooperation.

DR. BRANDT Is such intervention at age four or five relatively frequent, infrequent, or rare?

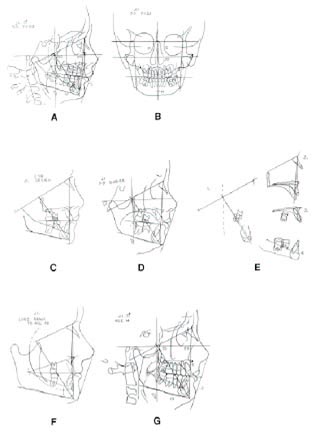

DR. RICKETTS It is as frequent as I can get them. I have been doing it since early in my private practice and start regularly on all patients coming to me who have conditions which early treatment will help (Fig. 2).

DR. BRANDT What records do you accumulate when you start treatment on such young patients?

DR. RICKETTS All the records which I obtain with any other patient. That means a frontal and lateral headfilm, laminagraphs on both sides, a panoral film, and photographs. Failure to diagnose and prognose at this age is one of the big mistakes many orthodontists make. They do not realize that this is an orthodontic candidate and that serious treatment is starting. They sometimes neglect taking complete records because it is only a preschool child with "baby" teeth. Remember, this is still a human being and is entitled to every attention you can give, no matter what the age. In fact, diagnosis and prognosis are even more important because you have more uncertainties now than in the adult, because you must now anticipate growth and jaw development.

DR. BRANDT Some parents will frown when serial radiographs are done on their children. When they discuss this with you, what do you tell them?

DR. RICKETTS First, I tell them they are necessary to define the problem. Diagnosis and planning are even more critical here. I tell them the records are used to study growth progress, and that we'll take no more x-rays than we feel are essential. They are surprised to find out that taking of a head x-ray is not nearly the amount of exposure that occurs with the simple tooth x-ray due to intensifying screens and target distance. Schulhof cleverly worked out the probability of having biologic damage to be about the same as the risks in travel to the office (in the United States). In some countries, the risks of the drive outweigh the x-ray risk.

DR. BRANDT Is growth prediction or estimation an essential part of your diagnosis in deciding upon early treatment?

DR. RICKETTS To me, growth prediction is a strong influence on the decision. How can anyone know how big an arch will need to be or how much space will be available for teeth until an estimate of size and form is made to the stage of maturity? If you are going to make decisions with regard to serial extractions, the use of extraoral traction or arch expansion, you had better have an idea that your chances are good. Otherwise, you will be obliged later to correct the treatment mistake you made or practice what one observer called "supervised neglect".

One of the factors which has disturbed orthodontists so much in the last two or three decades is that they would see a young patient and assume an obvious serial extraction case. They would remove the deciduous canines, first premolars, and sometimes also enucleate bicuspids. Years later a flat face and a flat mouth resulted. I went through a time in the '50s when I did some serial extraction based on noted authors' recommendations.

But serial extraction is extremely rare now in my practice. This is because I ended up treating many of those patients later without bicuspid extractions. When this happens, you wonder why deciduous teeth were extracted in the first place. I took away teeth that the child could have used for three to five years. Now I often don't leave them crowded. I increase arch length and obtain space in the "interceptive" phase. My hunch is that too much serial extraction is practiced and seems to be most popular with those who do not work with sophisticated growth forecasts.

DR. BRANDT Are growth predictions for early intervention cases divided into long and short range, encompassing both the mixed and permanent dentition?

DR. RICKETTS Yes. These forecasts can be seen in the case in Figure 2. Only since 1971 have we had what I could truly call "growth prediction". This has been a long struggle, but I am convinced we have exceedingly trustworthy procedures by which, at the early age, the future size and form of a patient's jaw can be determined within practical limits. This is at odds with other research workers, but many of those haven't attempted to learn or understand the recent procedures. I don't think they would take an adamant stand against growth prediction if they did. One problem perhaps is that some are committed to the idea that it can't be done. Other biologic researchers must take second place to the clinicians' needs, and a forecast with a minor error is better than a wild guess or a delay due to fear.

For the record, until 1971 I never claimed that I could make a long-range prediction with any degree of certainty. The short-term forecast was first attempted in about 1950. This initial procedure amounted to a projection of only two years of average growth. It made little difference whether the patient grew exactly that much or not in two years. Whenever the growth (fast or slow) occurred, that amount was put into the anchorage equation so growth could be entered as a contribution to the correction and the amount of tooth movement left could be seen.

We added the effects of treatment and autorotation caused by bite opening or by extrusion of teeth from the pull of intermaxillary elastics or the leveling of the curve of Spee. Both procedures rotate a mandible backward, due to the fact that the mandible is held open by extrusion of teeth and against the pull of the muscles.

The third factor added was the tooth movement required to make the correction of the malocclusion. Frequently the amount of tooth movement was several times more than the amount of growth change.

The fourth factor was the resultant change in the lips and soft tissue as determined by findings from similarly treated cases. In reality, therefore, a short-term forecast for a patient with a malocclusion to be treated was more a prediction of whether or not you could move the teeth and where you decided they needed to be placed than a growth prediction alone (Fig. 2C).

What we were really doing was setting up the teeth in a tracing as you would set teeth up in plaster but, of course, with much less effort and cost. The original short-term projection was nothing more than a cephalometric tooth setup.

But, somehow or another, it got labeled "prediction" which was unfortunate. In the two-year short term, only 5 to 6mm of growth will usually result on the central facial axis. The rest of the setup is what you as an orthodontist think you can and should do. Figure 2E shows the analysis of change by the four position method.

The mixed dentition age or earlier is really when the long-range forecast becomes useful (Fig. 2F). This same patient at age 14 (Fig. 2G) had developed an ideal occlusion and that was the last time we were able to get him back to the office.

If you take a boy at 15 or 16, or a girl at 12 or 13, only two years or so of growth remain, and so short-term and long-range become the same. The orthodontist is limited from actually using growth, altering growth or producing skeletal change when he waits too long. That is one reason for starting the patient early.

DR. BRANDT Can a growth prediction suggest that a Class I double protrusive malocclusion will improve because of favorable growth and the protrusion just disappear? Can the crowded dentition be predicted to unravel the overlapping teeth?

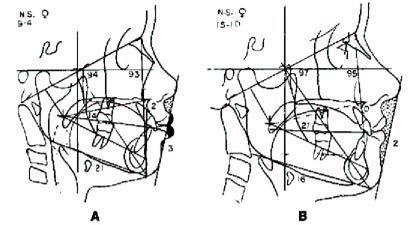

DR. RICKETTS Certain Class I double protrusive patients have been demonstrated to grow out of the condition. I have patients in whom the prediction actually kept me out of any treatment at all (Fig. 3). Angle showed this in his textbook in 1907, where he demonstrated a patient in which this had happened. The implication at that time was that this could be expected in most patients, but it doesn't always occur. Brodie showed this in a publication in the early '50s. That is why growth prediction is essential.

By predicting nose growth and the direction of the growth of the chin, we can ascertain the probability that a patient will grow out of a protrusion. This is one of the great applications of long-range forecasting. In retrospect, I now know that some of my double protrusive extractions in young males would never have had to be done.

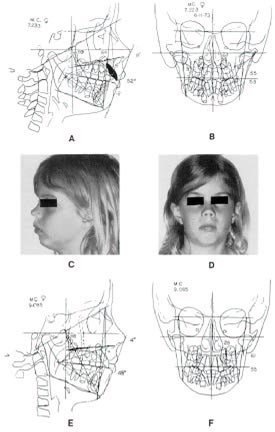

I also have a patient who grew out of a Class II between age 7 and 12 after I had prescribed removal of large adenoids (Fig. 4). She is shown at 23, but grew little after 13.

When it comes to the prediction of the unraveling of teeth, I frankly haven't seen this occur in many patients, particularly in the lower arch. Once in a while you will see upper arch crowding become minimized as the lower jaw carries the dentition forward and the upper teeth have a chance to spread out. They erupt to compensate for the forward development of the lower arch. I have shown this in publications. But I just don't count on it happening very often when I see crowding in the lower arch. That doesn't mean they cannot be expanded and hold. Some of the unhappiest results I've had have been spaces reopening in double protrusive cases. I'm retreating one male now in his mid-twenties.

DR. BRANDT To sum up this phase of the discussion, would you suggest that all growth patterns--good or bad--are candidates for early treatment?

DR. RICKETTS The variation is so great that I consider all growth patterns as requiring growth prediction at the early stage. Any patient who presents with a malocclusion is worked up in my practice--now, thankfully, by the computer laboratory. It's the best service I can give my patients, in my opinion, to give the best judgments for treatment.

DR. BRANDT Let's move on to another area which is getting increasing attention. There is growing concern about the nasal airway function. Can this be related to early orthodontic treatment? Will such orthodontic intervention have a lasting effect?

DR. RICKETTS This is another subject dear to my heart! Now we are getting into function and the answer is an exciting "Yes!" From the environmental standpoint, total respiratory function has been the most overlooked factor in clinical orthodontics. The influence of the beliefs in the '30s and '40s--the concepts of genetic dominance and the conviction of limited skeletal alteration as a possibility in therapy--led to the concept of treating just the teeth instead of the face or the patient as a whole. Information collected on failures now seems to suggest evidence of corrected respiratory problems, and not just adenoids and tonsils, but the entire mechanism of any respiratory obstruction. I wrote on this in the '50s and '60s as well as the '70s, but the profession's majority still takes only lateral head plates and really only a few heed the airway problems.

DR. BRANDT If the nasal airways have ceased to grow or expand, could this be tied to lack of function?

DR. RICKETTS Most orthodontists and researchers in growth simply haven't looked at the nasal cavity as a vital vegetative part of the face. We talk about the oral cavity as if it is independent of the development of the first branchial arch and independent from respiration. Biologically, the functions of mastication and respiration have been connected with the same set of muscles and the same set of nerve paths. We can't separate them.

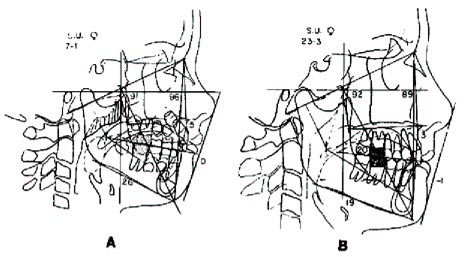

When we observe a lack of function in the nose, we know there can be growth inhibition. Harvold proved this in monkeys experimentally! It may be seen on only one side of the nose as the other side serves as a normal control. If you study frontal headfilms, frequently you can see a small nasal cavity on one side and a larger one on the other. You may find that the patient had a unilateral obstruction and see the whole maxilla sucked inward and upward on that side. I'm sure you have seen models of the maxillary arch and have said, "Look at that funny maxilla". Yes, the nasal cavity should have received more of our attention long before this. The best place to start is by taking routine frontal headfilms and look for symmetry of the nasal cavity. That is one of the primary uses of the frontal headfilm. Figure 5 demonstrates the effects of removal of adenoids, palatal expansion, and orthopedic headgear.

DR. BRANDT What is microrhino dysplasia? Are such conditions seen frequently in orthodontic offices?

DR. RICKETTS I picked up this term from Dr. Peter Bimler in Wiesbaden, Germany. Bimler was an ENT specialist before he became an orthodontist. He paid much attention to the nasal cavity. He developed his own cephalometric analysis, and one factor (#4) was the level of the palatal plane to the Frankfort horizontal plane. We in America mostly had related the palatal plane to the SN line as Brodie and many others had done. When I was first exposed to Bimler's idea, it immediately was intriguing because of my interest in the growth of the nose and the nasal capsule. If the nasal cavity isn't developing properly, the tilt of the palate will frequently be elevated in front, as if it has been stopped in its vertical growth in the anterior part (Fig. 6A,B).

This discovery came after I had already realized there was palatal alteration with cervical headgear, and gave rise to a saying in my teaching. "Don't think teeth, think jaws". Most orthodontists in the past thought in terms of the occlusal plane, rather than in management of the whole palatal plane or alteration in the skeletal midface.

The lack of function in the nose seems to hold the front of the palate upward or prevent its downward descent. When you see these children clinically, you look right in their nose holes, and the whole nose appears to be higher relative to the orbits (Fig. 6C,D).

A microrhino case (microrhino meaning small nose or small nasal cavity) will develop on its own from lack of function of the nose. But I also see palatal inhibition as a result of certain kinds of vigorous thumbsucking in which a patient gets the whole shank of the thumb up into a markedly open bite and actually inhibits the downward dropping of the palate anteriorly.

I'm convinced that microrhinism can be caused by a finger or thumb factor. We see the opposite action from the headgear when we see the palate altered downward and backward from cervical traction.

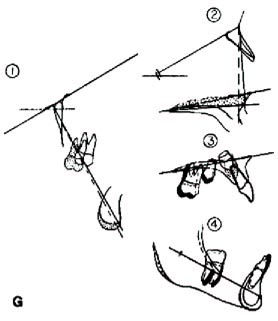

The microrhino patient who has a thumbsucking habit is a very good prospect for us to manage orthodontically with extraoral traction, particularly with the Kloehn headgear. We can bring the palate down and tip it backward and correct the malocclusion, moving the teeth hardly at all (Fig. 6G). We can do it with a skeletal change rather than doing it by movement of the-teeth. That is a remarkable concept because it is a real opportunity to treat without trauma to the teeth. We can also permanently alter the patient whose microrhino condition was caused by abnormal nasal function, if we can get the patient to function normally.

Now we must get into the causes and look further into the problem as to why and what type of microrhino case specifically it is. It could come from allergies and asthma or even potential adenoidal obstruction. Maybe also some patients just have small nasal cavities. Under normal function in breathing, Gray has said a pressure develops. Perhaps in the abnormal, this pressure is changed to a vacuum and the maxillary complex is sucked inward, restricting the basal bone. It's up to us to create new basal bone!

DR. BRANDT What would happen to the microrhino child if therapy were not applied?

DR. RICKETTS An imbalanced facial height results in the untreated child. I have seen adults socially in whom the nose is short, the nose tip is upward, the nostrils show, the upper facial height is short, and the denture height is extremely long. These cases are very difficult to treat later without surgery in the maxilla because of the extreme distance from the anterior nasal spine to the chin, requiring a stretching of the lips and creating inordinate strain over that dentition. Later, with large denture height, teeth often are extracted or held backward; and still the patient ends up with mentalis action to compensate for the high denture height. Even with extraction, these patients still possess gummy smiles if you wait, no matter how good a wire bender you are. The denture height and lip line do not match.

DR. BRANDT Rick, are we paying enough attention to the freeway space? Should it be measured on all patients, and if so, how do you do it?

DR. RICKETTS Even though I did years of work on the freeway space, I don't give it much attention any more in the typical orthodontic case. When you begin to deal with freeway space, you get misled into some erroneous concepts. I don't pay much attention to it except in TMJ cases. Wide freeways may be indications of breathing problems or tongue thrusts, however. The main issue is that I don't let it influence my judgment for correction of the malocclusion.

DR. BRANDT Physicians seem to be placing less importance on tonsils and adenoids. These are not excised as regularly as they were in the past. Has this ever created any conflict between you and the child's physician? Are you apt to recommend the removal of these tissues on your own initiative, and does this leave the parents confused?

DR. RICKETTS We have a serious communication problem with the pediatrician, with the general physician, and even with the ear, nose, and throat specialist. They are no better trained in the function of the nose than we are, or maybe not informed as well. This is why we have to give this particular area more research attention. The idea that the adenoids and the tonsils were foci of infection was the same concept that we had with the periodontal foci of infection. Consequently, the patient had his teeth taken out and had the adenoids and tonsils removed uselessly.

In later years, it was held that gamma globulin, an antibacterial agent, was being produced by the lymphoid ring. Now science is coming up with the concept of the viruses. With the virus and cancer connection, some people say, "If you take the adenoids and tonsils out, you're subjecting this child to the possibility that he will be more apt to have cancer in the future". This has gone to such lengths that many physicians may completely ignore adenoids!

But, if you study the work of Linder-Aronson in Sweden you will find that he has shown exactly what I theorized in the '50s: adenoids could lead to an opening growth rotation of the mandible. You are dealing with not only an inhibition of maxillary growth but also an alteration of mandibular growth in a patient who is effectively obstructed in the nasal cavity. With this kind of information, we can be very strong in our recommendations, particularly when patients' x-rays confirm the diagnosis (Figs. 4 and 5).

In dealing with the patient and with the parents, I will be very firm to the point that I say, "If I go ahead and treat without adenoid removal and there is a relapse, I want you to know that it's your responsibility and the physician's responsibility, and my full fee will have to be paid again to re-treat". I protect myself in the responsibility of treating a crossbite unless I can get this patient functioning correctly.

What I have done in situations is to simply call up the patient's physician and say, "Look, I'd like very much to have a meeting with you. Let's establish a rapport. You can be certain that if I refer a patient to you, I'm not doing it idly and I have a good reason for doing it. Every patient who comes in who has adenoids is not going to be sent to you. It's only the case in which I feel we have a responsibility to help each other with the growth of the patient's jaws, his welfare, and his sense of well-being". When you approach the physician on that level, you'll earn his respect and the right to be the diagnostician in this field. Remember, the tonsils may be left. It's not necessary to have both a tonsillectomy and an adenoidectomy.

(CONTINUED IN THE NEXT ISSUE)