Patient Motivation

Some orthodontic techniques rely on cooperation more than others, but all of them fail without it. Yet, while the orthodontist is well trained in techniques of mechanotherapy, relatively little time is devoted to patient motivation. This paper is based on practice-tested application of fundamental psychological truisms in patient motivation.

The Personality of the Orthodontist

As we examine ourselves, we certainly see how we differ from others in our personality traits. Many of us, as we strive to motivate our patients, will take the same ingredients and mix them differently, putting more emphasis on some than others. My approach is a way to do it. It has been highly successful in a very busy private practice. It has been developed over a period of some years after a series of problems and mistakes that were made in the process of trying to establish a professional "image". Establishing a list of motivational facets, let us first discuss respect.

Similar articles from the archive:

- MANAGEMENT & MARKETING A New Paradigm of Motivation June 1996

- CLINICAL AID Motivating Frankel Patients April 1984

- Mr. Moto's Motivation Chart September 1973

Without respect motivation is pretty difficult to achieve. If we expect youth to implement the scout precepts, or any other set we regard as desirable, we must set a good example. Respect is based on the appreciation of success that another person has, and on certain character traits that one admires and would like to emulate. To respect and be respected is a prime requisite for any orthodontist who would desire his patients to follow instructions.

A second element of the orthodontist's personality is enthusiasm. If we like our work, and we have every reason to do so, if we realize how lucky we are to work with children and "in-betweens", why not let them know it?

There is no time that is more important to impart warmth and obvious interest in the patient, than at the first visit. First impressions are important for all concerned. A firm handshake, a friendly smile, an informal manner, a relaxed attitude and an obvious impression that you enjoy the meeting and what you are about to do are important.

The child, and not the parents is the center of attention, and should be kept that way. Using our own approach as one example, with informality the keynote, we greet the parents, usually ask who referred them as an opening conversation piece, but then turn our full attention to the young patient. The child is addressed in a disarming manner: "Let's look at your choppers and see why you are sitting in the dental chair instead of enjoying school", or something similar. We apologetically remark that we will dictate a few notes, after which we will talk about the problem if any exists. After a rapid-fire clinical examination that is recorded in shorthand by the assistant, or on a cassette recorder if she is not available, a description is given directly to the child in terms that he or she can understand. Something like "Mary, your upper and lower teeth do not meet properly and that is why Dr. Smith wanted you to drop in for a checkup. You probably are concerned about how your teeth look. Your mother, your dentist and I are concerned about your dental health first. You may or may not be ready for us to put on braces to straighten your teeth. The first thing we must do before deciding is to see what the iceberg is like under the water."

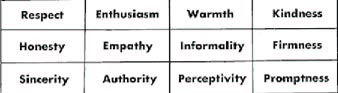

Motivational personality traits of the orthodontist.

A relaxed description of the need for models, x-rays, photographs, etc., is given directly to the child, but the parents obviously can hear too. Then, "After we have gone over and studied your records, Mary, we can sit down with your mother and dad and you, too, if you wish, and decide what has to be done, when, why, and how big an investment must be made by your parents in your dental health". Fee ranges, miscellaneous questions, etc., may then be answered for the parents. The child has the message. She is the center of attraction, and we are interested in her! You might call this quality empathy. It is a good one to develop. The confidante of the adolescent must have it. The motivational potential is significant.

In orthodontics, it is no exaggeration to tell a patient that he is a member of the orthodontic team, perhaps the major and most important member.

The strong patient orientation is confirmed by saying, "Mary, we are happy to meet your mother (and dad) today, but if we take care of you, it won't be necessary for them to come in more than once every three months or so for a progress report. After all, it is your teeth and your responsibility and we can work this out together". If we decide to take records the same day, we politely ask the parents to wait in the reception room. They stay there from then on, unless they make a specific request for a consultation or unless we ask them into the operatory. Discreet colored cartoons, provided by the American Dental Association, adorn one wall of the waiting room, giving this message. Parents are important assists in motivation, but their role is at home and not in the office.

Another characteristic that should always be an ingredient of patient motivation is to be honest and sincere. A youngster can sense insincerity immediately, and he shows it plainly. Always look a child directly in the eye when you talk to him. Never try to be patronizing or "talk down" to a child.

Part of being forthright is the kind but firm attitude. The office is built on discipline, as can be seen immediately by observing the auxiliary personnel. No one sits around. Likewise, there is a discipline in handling a patient. It might be defined as a sort of "esprit de corps", a rapport based on respect, kindly firmness and authority.

Authority is a key word. There is a time and place for it. With some youngsters, obviously, it would be a mistake to "read the riot act?'. With some, for example for an appearance-conscious child, the orthodontist need only fan the fires of self-motivation. With others the fear element may play a part in motivation (extraction of teeth, for example).

In this game of attitudes the astute orthodontist must be a clinical psychologist, and exploit those avenues likely to produce the best result. It is important to be perceptive of the patient's attitudes, fears, training, environmental influences and reaction to the prospect of wearing "braces". A simple question like, "How do you feel about braces, Mary?" can give an opening and significant information. Often, the patient will volunteer valuable information on attitudes and fears before any questions are asked. Don't cut them off.

In the orthodontic motivational armamentarium should be a strong sense of the importance of a promise or a threat. Try hard never to break a promise with a child. If you must threaten to remove appliances, unless cooperation improves, and this is occasionally necessary, then be prepared to carry out the threat. Too many parents talk a good game, punishment-wise, but don't deliver. Idle threats are poor motivational factors for the orthodontist, parent or teacher.

Promptness is another orthodontic personality motivational factor. Too few orthodontists have their office geared to promptness. If you are late, apologize to the youngster, and mean it. His time is as important to him as yours is to you. If he is late, he should know it in the sense that he is inconsiderate to other patients, who must wait.

Penetrating the Adolescent Armor

The literature is replete with the problems of the adolescent: the rejection phenomena, the antagonisms, the contradictions, the cloud nine withdrawals, the hyper-emotionality, etc. In this change from child to adult, in the transitional period, many children build up a protective armor. Motivation becomes difficult, particularly for the parent or intimate relation of the child. The orthodontist has a tougher job at this time, yet he has an advantage over the parents. How many times has the parents said to you, "You tell him what to do. He won't listen to me at all, but he respects you!"

The success or failure in achieving maximum motivational potential is directly dependent on the personality factors of the orthodontist, and on his understanding of the transitional insecurity. Yet, if he can blend his position of respect, his enthusiasm, kindly firmness, humor, empathy, sincerity, relaxed informality and obvious love of work, it will be easier to achieve optimal success. If he does not try, he will meet a stone wall of silence and rejection, with an automaton-like response in the office. Once the child leaves the office, motivation drops to ground zero.

The Personal Touch

Since we always want the patient to feel sincerely that he is the center of attention, and since we cannot remember all the names, the patient record is placed behind the chair so that the name can be read easily before we see the patient face to face. He always is addressed by his first name, along with some personal comment or question about school, weather, etc. Augmenting this personal approach, we often try hard to give the patient a feeling of participation. We start out the first visit by letting him press the cable release on the camera to take his own pictures, press the hand control to take his own headplate, etc. Later on, he may package his own elastics, and will be called upon to show another patient how to wear a headgear. He will discuss how he cleans his teeth and answer questions for new patients. At times, for girls who show a great interest, we let them help us with sterilizing. We give them part time jobs after school or on Saturdays, assisting, putting statements in envelopes, and similar tasks. This has a salutory effect on patient cooperation. Try it and see!

In line with a feeling of interest and participation, the patient should be motivated by letting him know the progress he is making. Take out a set of original models, photographs or headplates and show the change every third visit or so. Progress is slow enough and the patient who sees his teeth every day may not be able to see any change, or reason for cooperation if he has been following instructions and nothing apparently is happening. Do not let him get discouraged. Conversely, where there is lack of progress, apparently due to lack of cooperation in wearing appliance or elastics, the patient should see this, compared to a similar case showing the dramatic change because of patient cooperation.

Oral Prophylaxis

One of the most persistent problems all orthodontists have is getting the patient to brush his teeth properly. We have tried practically every approach and have failed with some patients, regardless of the bagging, cajoling, threatening, showing the damage possible etc. Our present procedure has reduced decalcification significantly. The group pressure of a multi-chaired operatory helps, but the real clincher is the so-called "chemical neutralizer technique". When a patient comes in with dirty teeth, we re-emphasize how important toothbrushing is, and show him again how to brush the teeth. He has already seen a slide-tape sequence and has been instructed by the hygienist. Disclosing tablets are used to dramatize the debris-bearing areas. The patient is told that food decays and forms acids which attack the tooth structure. Permanent zebra stripes will last a lifetime as a result of the acid action. So if the teeth are not clean at the next visit, and if the parents tell us that there are difficulties in maintaining proper home hygiene, we will help by administering a "chemical neutralizer treatment."

One of the handiest acid neutralizers is soap. The next time, if the teeth are still dirty, a large brush is thoroughly soaped and the patient told, "Oh, I am so sorry you are having trouble brushing your teeth, John, but you know acid is forming in the food debris and we must neutralize it immediately to prevent further permanent disfigurement! Regular toothpaste will do this too, if you use it at home, but soap is extremely effective. Here, I will show you." The brush is massaged vigorously over the incisors while the other patients grin broadly at the predicament of the unfortunate, "Mr. Dirty Teeth". While the massage is being given-- and we are not too careful to keep the soap off the face-- we apologize for having to do the "treatment" but, "We are confident that the alternative of stain and decayed teeth would be infinitely worse."

The final "convincer" is again couched in scientific verbiage of acid versus base reaction. An announcement is made that if there is still trouble at the next visit, we have a stronger, even more effective base, like laundry soap. If this does not work, there is always Ajax, the foaming cleanser! We have occasionally had to use laundry soap, but Ajax is still on the shelf. The message is clear; the need for prophylaxis is obvious. The unpleasant taste and peer pressure and embarrassment are strong weapons against a repeat performance. The "Gee, I hate to do this, old man, but we must help you all we can" approach-- the sympathetic understanding smile, the wink of the eye are potent assists in this technique.

A related problem is excessive appliance breakage, or a succession of appointments where a patient will have loose bands. This subject is discussed under the heading of financial motivation, along with the policy of charging for continued and unwarranted breakage. Before any charge is made, however, we appeal to the group pressure with other patients present, while we discuss the problem of "diet don'ts". It is pointed out that breakage interferes with progress, may cause permanent damage to the teeth and is costing the parents more money. The message is not wasted on other potential appliance breakers in the room, who may demur when next offered a caramel. We try not to seem angry, but more shocked, or sort of let down by something we just did not expect from a mature motivated patient. When the assistant says, "Doctor, Joe Blow has a loose band," I will likely turn and say, "Stop kidding me! He is too reliable and mature a patient and knows the things he shouldn't eat." Is this corn? Probably, but it seems to work rather well. If it doesn't, the charge is assessed against the patient directly. This has potent motivational aspects.

Patient Education

A knowledgeable patient is a better patient. An attempt should be made to explain things to the patient in terms he can understand and can repeat at home. As indicated previously, we direct our remarks to the patient and not the parents, even when we are making our examination. Not all patients are interested to the same degree; many patients are preconditioned by comments from other children who are having orthodontic therapy, or by what their parents have told them. This, of course, is a form of education. It is the responsibility of the orthodontist to offset any misinformation that may have been given. The doctors try hard to answer questions personally, and we have our staff do the same. In addition to the direct discussion, patient education booklets and audio-visual sequences are a part of the educational armamentarium. A number of excellent educational booklets are available from the American Association of Orthodontists, the American Dental Association, etc. The use of a film-strip record or slide-tape sequence is an excellent way to see that important information reaches a child in a form to which he is receptive and from which he will retain the greatest part of the information. The cartoon type audiovisual sequence of six to seven minutes duration does not exceed the attention span of the child. The AAO audio-visual patient education sequences, developed by C. V. Mosby, fit nicely into the office routine and are to be recommended. Problems of diet, appliance breakage, treatment objectives and methods of handling are all well illustrated.

Other informational assists may be available that are particularly useful during the initial exam and during the consultation with the parents. A magnetic board, for example, allowing the orthodontist to shift teeth around and simulate a malocclusion is an effective way of demonstrating the nature of the problem and the treatment challenge. A series of preselected cases is also a good idea, with "before and after records" to demonstrate what can be done.

In the use of the multi-chaired operatory, a valuable educational assist is to have another patient, with a similar problem, come over and discuss what he does and demonstrate his headgear, bite plate, method of brushing teeth, etc. This motivates both the new and old patient. Like everything else, patient education can be overdone. A long technical audio-visual sequence will mean little to the child. Some parents are quite sophisticated, having had other children go through the process before and a barrage of information may be "old hat" for them. Discretion is the order of the day.

Pleasant and Efficient Environment and Personnel

A study was made of the most pleasing colors for hospitals, medical and dental offices, etc. Surprisingly enough, the most anti-neurotic color was a pastel yellow, with a soft green, a close second. The use of wood paneling if not overdone, provides a feeling of warmth and coziness and removes the institutional flavor that so many offices have. Full carpeting (indoor-outdoor type) is strongly recommended for noise control, warmth, comfort, as well as decor. Flowers or plants are a "must" and they not only help the patient, but those on the staff who spend the entire day in this environment. Soft background music is desirable. The emphasis is on background, for in some offices it is pretty difficult to talk above the level of clashing cymbals from the booming HiFi.

In addition to pleasant colors and appropriate music, the reception room and operatories must have good lighting and a good selection of magazines. The fluorescent light quality is more desirable for the operatory, with incandescent lights providing a softer glow for the reception room. This does not mean that the reception room has to look like the intimate cozy corner of the neighborhood tavern. The lighting can be too dim as well as too bright.

Multi-Chaired Operatories

Having had continuing experience with both single-chaired and multi-chaired operatories, over a long period of time, we have formed some rather definite ideas. The ideal would be to have one single-chaired operatory for examinations and consultations, and a multi-chaired "treatment operatory". The single-chaired operatory may also be used for adults, or for special "heart-to-heart" talks. The goals of treatment, the efficiency of service and potent patient motivation are better served when you have three or four chairs in the same room. The room may be broken up by low-level dividers, flowers, mobiles, etc., but the broad expanse, spaciousness and light are beneficial for all concerned.

Corollary to making pleasant surroundings for patients and office staff is pleasant personnel. Too many girls are coldly efficient and have forgotten how to smile, although it is still possible to be efficient while being pleasant and informal. Most patients like to think that there is some real personal attention, concern and warmth. Quiet, smiling, neat, clean and efficient personnel set the tone of the office. Some of the "happy" feeling is bound to rub off on the patient.

As part of the pleasant environment is the office attire. White implies cleanliness, but it can also enhance apprehension, particularly for the younger patient who associates it with the pediatrician, hospital etc. Our chair assistants wear green uniforms, the secretary wears pink and we wear a golden tan sport shirt-like smock. Patient and parent reaction is that this is "mod", forming yet another tie, bridging the generation gap.

Programming Appointments

To have time to provide personal service, an orthodontist must see his patients routinely during the entire working day. It is absolutely impossible to achieve optimum motivation with fifteen to thirty patients jamming the waiting room after school. As part of an efficient setup, permitting better service at a higher level of motivation, all grammar school children must come for their adjustments at approximately four-week intervals during schooltime. For high school, it is alternate appointments during school.

The following is one effective means of making sure that the parents understand this desirable aspect of our office routine. We say very pleasantly and quietly, at the first examination, "By the way, we accept patients on one condition only-- all appointments must be during school if the patient is in grammar school or every other visit if he is in high school". The response serves to weed out the "shopper" or the demanding parent that is doing the orthodontist a favor by coming to him. If they accept the condition, they then realize psychologically that this arrangement is not completely a matter of their own choosing. Very few, indeed have been offended and have not accepted this conditional response.

It must be stressed, however, that the statement must not be made in an imperious manner, but must be done in a pleasant, smiling and intimate tone. If the parents insist, "But I can't take my child out of school every time!", we patiently explain that special school excusal forms have been developed for the procedure. The child will be out of school for as short a time as possible. In most

instances the total elapsed time of transportation and adjustment will not exceed one hour every month. It is pointed out that better service can be rendered by working this way all through the day, that we can motivate better, that we can get the treatment done more quickly and that we will not be keeping the patient waiting for long periods of time. It is not fair to crowd everybody into the waiting room at 3:30 and then try to render a proper adjustment when there simply is not time available. It is stressed that the child is a better patient before he has been tired out by the school day routine, that extra-curricular activities after school are also important, and that the appointment may be fitted in with a minor subject, gym, lunch hour, etc.

Financial Considerations

"Protecting the investment" may serve as one of the stronger motivations, clinically and otherwise. It is possible to motivate the patient by motivating the parent through the pocketbook. A child should know that the parents are making the sacrifice, that money being spent on him could be spent on trips, personal possessions, etc. The parent obviously overhears us telling the child that we are aware of the financial sacrifice being made and we know that the patient appreciates it. The reaction is favorable.

A real motivational aspect of the financial arrangement is the closed end fee. At the time of the first examination the parent is told that we will assume that the average case takes a year and a half to two years. We say that we will know better, of course, after the diagnostic records have been made and we can tell them about the particular problem. But because of the variability of tissue response, patient cooperation, growth and development, etc., we set a top fee. An initial fee of so much is charged and then a monthly or quarterly fee is assessed. There is a limit to the number of months or quarters for the financial indebtedness. In no event will the top financial limit exceed this time limit. If we get done sooner, the total amount is not billed. While there is a charge for each retainer, there are no per-visit charges. The message to the parent is that the harder the patient works, the sooner we are done, the more the parent can save. The parent is told that they may let the patient have the last month's "fee" for doing a good job if they desire. We are anxious to terminate the case successfully as soon as possible as they are, for we are all working on the same team. If the child has a headgear, then it is up to the parent to help the patient see that it is worn every night, not only for the sake of treatment progress, but because it is throwing money out the window if the appliance is not being worn.

We do have some flat fee cases. It is so easy to set a flat fee when the demand is great for services. Yet with flat fee cases, the parent is somewhat resigned to a definite amount, is less likely to be cooperative and less likely to help motivate the child at home. Flat fee cases seem to take longer and the level of patient cooperation somehow does not seem to be quite as good. In addition, it does not create a favorable reaction from parents who must continue to pay on a flat fee basis after the appliances have been removed.

The closed end fee permits somewhat more parental pressure on the orthodontist as he approaches the end of treatment as the parent wants to know how soon the appliances will be removed. This is one of the necessary evils of a better motivational setup. We are quite willing to explain that we will remove the appliances just as soon as possible after we have accomplished what will be a stable objective. Since the parent is kept out of the operatory after the first visit and is called in only occasionally for progress reports, the questioning does not become too onerous.

An additional motivation is the charge for appliances breakage. This is recorded in our memorandum letter to the parents. The first time or two we do not send a bill, but if it is obvious that the patent has tampered with the appliance or is eating the wrong type of food, in violation of the rules, the parent is called and told that there is a nominal charge, i.e., one that does not begin to cover the additional time and effort. This will be billed directly to the patient and should be taken out of his allowance. We suggest that the child be asked to wash dishes for a week or some other home chore to make this a very personal thing and to cut down future breakage. The procedure works quite well. There is a very small number of patients that are billed for appliance breakage each month.

Dentist Cooperation

A concerted effort is made to enlist the aid of the dentist, who is handling the routine dental care. A full report is sent to him, describing the nature of the problem and the plan of treatment, and asking that the patient be placed on four-month intervals for dental checkups. We ask the dentist if he will tell the patient how important it is to cooperate to get the job done as well as possible. We don't hesitate to call and discuss the problem and ask for help. Too many dentists feel that they no longer have their part of dental care when orthodontic treatment is in progress. There has been some resentment of the orthodontist who seems to "take over" the patient, forgetting the dental appointments during active orthodontic treatment. We have actually gone so far as to have a reminder phrase stamped on the statement every four months to make sure that dental checkups are being made. A notice is put on the wall in a prominent place to this effect in many offices.

Summary

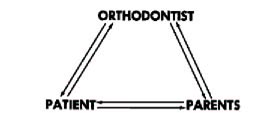

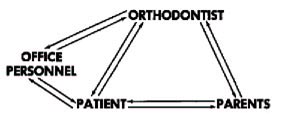

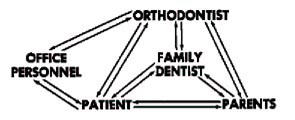

The ingredients of optimum motivation vary with different orthodontists, as well as different patients. But it is apparent that the orthodontist's personality, the psycho-social behavior of the patient, the impact of the office staff and office environment, the role of the parents and siblings, the cooperation of the family dentist and even the financial arrangements are all important. The theme is the team, the office team and the home team, working together.